This is Part 1 in a new series about Radical Municipalism, looking at ways that people worldwide are organizing in their cities to build power from the bottom up. Read Part 1 (Brazil) Part 2 (Rojava), Part 3 (Chiapas), Part 4 (Warsaw), Part 5 (Bologna), Part 6 (Jackson), Part 7 (Athens) and Part 8 (Warsaw & New York), Part 9 (Reykjavík), and Part 10 (Argentina).

“How many more deaths will be needed in order to end this war?”

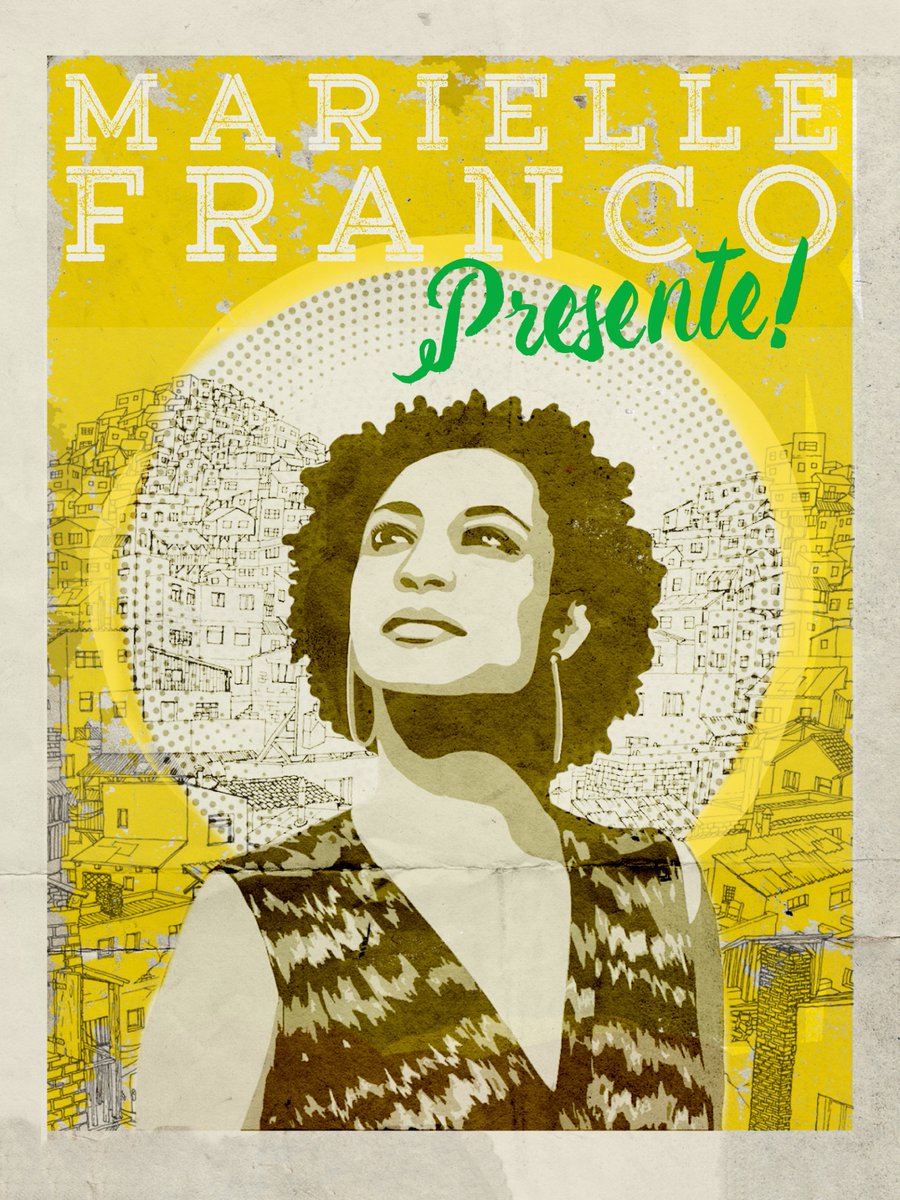

These were a few of the final words written Mar. 13 on Twitter by Marielle Franco, a day before her assassination. The 38-year-old city councillor from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, was later shot alongside her driver Anderson Pedro Gomes.

The murder of the Socialism and Liberty Party politician, sociologist, single mother and openly bisexual woman from one of Brazil's most deprived favelas, Maré, has since reverberated around the world. Evidence suggests police involvement.

Marielle was a leading light in Brazil's Feminist Spring, a new generation of Afro-Brazilian and indigenous women fighting back against Brazil's intensifying attacks against people of color, women, LGBT people and other oppressed communities.

Her shocking murder begged the question: Did the police kill Marielle? The councillor's last tweet accused the police of murdering a poor black man named Matheus Melo after he left a church in Rio's Jacarezinho favela.

Police Violence at its Worst

Marielle spent her adult life resisting the police war on the Afro-Brazilian community, something that had been legitimised as the “war on drugs”. In fact, Brazil's death toll in this war exceeds the lives lost in Syria and Afghanistan during official wars.

In 2016 alone, more than 4,200 people were killed by the Brazilian police. Ten percent of all homicides worldwide happen in Brazil. The war on drugs has meant a military and state police occupation of favelas, and incarceration for many people of color.

Even before her election as Rio city councillor in October 2016, Marielle was an ardent critic of police violence. Since 2008, she worked for City Hall investigating militias in which police were tied to homicide. As councillor, she coordinated a commission monitoring state troop actions in the favelas, an issue that has elevated Brazil's hard-right government. Alongside motive and their track record for murder, evidence substantiates police involvement.

March 14

While returning from a women's event on the evening of Mar. 14, two cars pulled up behind Marielle's vehicle. The location seemed pre-determined. It was a CCTV blind-spot. Nine bullets were fired. Four of them killed Marielle.

Bullet casings show they were police issue 9mm rounds. These trace to a batch of ammunition stolen in 2006, and were also directly connected to a massacre near São Paulo in 2015 in which three police officers and a municipal guard were convicted of murder.

The scene of Marielle's murder was soon covered in flowers and messages, including “Black Lives Matter” and “Police kill”. Thousands of mourners marched from her home favela of Maré, and many more filled Rio's streets, across Brazil and the world. A unifying call was “Marielle Presente!”

In the aftermath, global figures co-signed an open letter calling for an “independent commission comprised of prominent and respected national and international human rights and legal experts and tasked with carrying out an independent investigation of the murder.”

"Being a Black Woman is to Resist and Survive All the Time.” - Marielle Franco

Fighting against systemic violence led Marielle into politics. After a friend from the favelas was murdered, she started campaigning for the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL). In an interview, she explained: “Incursions in the favelas were growing, weaponry and public security debate came to the fore.”

In 2006, she used the slogan: "I do not want my money in the caveirão [militarization], I want my money in education."

Marielle studied sociology, taking part in new opportunities for night courses that were open to anyone. The cohort around her became dubbed the "favela intellectuals". Her reason to stand for the 2016 elections relates to her campaign slogan: "Eu sou porque nos somos." ("I am because we are.")

In March 2016, when a key activist couldn't attend a meeting because her own house was being demolished, Marielle asserted: “We need to have women in various spaces to defend our lives.”

Brazil's Coup vs. Feminist Spring

Since the coup that year that brought Michael Temer to power after deposing President Dilma Rousseff, Brazil has regressed back toward its military dictatorship era, including firing live ammunition against peaceful protesters.

“Their ‘new era’ for Brazil was austerity, neoliberalism and privatization – with rocket-boosters,” writes Vanessa Baird for New Internationalist Magazine. In the months since, laws against abortions and violence against women and the LGBT community have increased. The number of rapes in Sao Paulo rose by 38 percent after the coup.

Marielle saw abortion rights as an intersectional issue. “Black women make up the majority of victims of rape,” she said. “So, when I fight for [access to] legal abortion, I’m also fighting for the slums.”

In Rio's city council, Marielle's many initiatives included night-time "day-care" to enable young mothers to work and study, as she had. She battled for rights to the city for all, including access to transport, healthcare and education services. One change she supported was for night buses to stop more often in order to reduce the risk of rape and violence. In the autumn, she planned to run for Vice-Governor of Rio State.

In her death, Marielle is being immortalized as a global human rights icon. But as she made clear, she co-led a participative movement.

Brazil's Feminist Spring

Marielle's journey is part of an intersectional Feminist Spring, with momentum that formed from Brazil's 2013 protests against neoliberal attacks and social exclusion. Four months after Temer's coup, Marielle and 30 other women of similar backgrounds broke into the electoral arena, winning seats in city halls across the country.

Aurea Carolina is one example: She first broke the glass ceiling in Belo Horizonte's hip-hop world before doing the same thing in Brazil's fourth largest city hall. Samia Bomfim became the youngest elected councilwoman in the city of São Paulo after working as a leading activist since 2013. In Niterói, a town near Rio, Talíria Petrone was the most voted-for candidate.

All these women are from PSOL. At the muncipalist level, they work through democratic participation, a thread running through the global rebel cities movement. For their communication, online tools are essential, including the use of live web broadcasts.

Notably, the movement links to – and has been out in front of – the global feminist movement. For example, Brazil saw its viral #MeuPrimeiroAssedio (#MyFirstHarrassment) movement start in 2015, several years before the #MeToo campaign took off in the United States.

Intersectional feminism also connects with a broader feminist surge in Brazil, organized specifically against Temer with presidential elections on the horizon later this year.

One expression of Brazil's intersectional feminism was an open letter calling for the Feminist Spring to amplify through the PSOL. The letter, co-signed by Marielle along with other previously mentioned PSOL candidates, said:

“The current moment demands an intersectional feminist policy that identifies the interactions of different forms of domination and discrimination with power structures and that captures the consequences of patriarchy, sexism, racism and discrimination against lesbian, bisexual and transgender women.”

It continued:

“The '99% Feminism' is a synthesis of a type of feminism that connects women's struggle to anti-capitalist struggle processes on a global scale, much inspired by the manifestations that emerged in 2011, from the 99% slogan against social inequality incarnated in the 1% that concentrates the global wealth.”