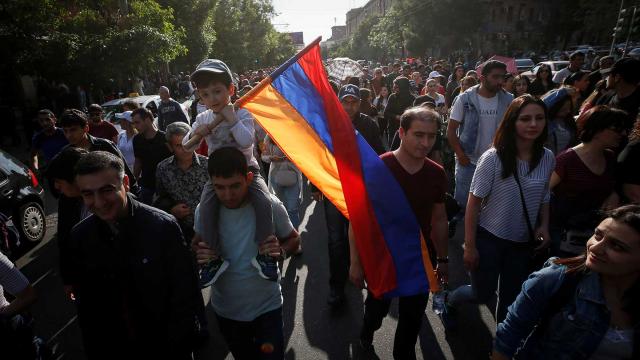

A boy holds a national flag during a rally of Armenian opposition supporters in Yerevan, April 30, 2018. (Reuters / Gleb Garanich)

Imagine a scene with a massive crowd of people set in a city of reddish tuff buildings, street signs written in an ancient script, and surrounded by biblical mountains. Envision people from all walks of life—students, teachers, workers, artists, journalists, clergy, soldiers—smiling, laughing, and hugging one another. A sea of flags with red, blue, and orange colors fills the square, and taxi drivers are honking their horns and popping champagne. The atmosphere is stirring and electric! These are ordinary people who stood up for transparent and accountable government. They mobilized to fight for a cause from a grassroots level, and they eventually won against almost impossible odds.

This was the scene on Monday, April 23, 2018, at Republic Square in the center of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. The people of this small former Soviet republic in the Caucasus had just heard the news (at first seemingly unrealistic) that Serzh Sargsyan had resigned from the post of prime minister. Sargsyan has served two terms as president, since 2008, and has been involved in Armenian politics in some capacity since 1990. With the switch to a parliamentary political system (similar to that of neighboring Georgia) in 2015, the oligarchs around Sargsyan persuaded him to remain as prime minister in order to protect their interests. Earlier, in 2014, he had publicly vowed that he would not seek to continue his tenure as prime minister and that he would step down in 2018.

His abrupt volte-face earlier this month triggered a protest movement to keep Sargsyan accountable to his earlier promise. It began as a small movement of mostly middle-class students led by Nikol Pashinyan, a muckraking journalist turned politician. However, over time it evolved into a mass movement, involving men and women of all social classes and age groups. By Friday, April 20, Yerevan’s Republic Square was packed with peaceful protestors. This was a surprise to even the protest leaders, including Pashinyan, who has become something of a sensation on Russian TV (his parents, from the Armenian town of Ijevan, expressed great pride for their son on the RBK network). At first, Sargsyan refused to yield to the crowd, but in the end, he resigned on April 23, one day before the commemoration of the 1915 Armenian genocide. It was an incredible act of statesmanship on the part of the outgoing Armenian leader, but more than anything, it was a victory for the Armenian people. “I was wrong,” Sargsyan wrote in his unprecedented resignation letter.

Even more remarkable were the subsequent developments. Upon Sargsyan’s resignation, the liberally minded First Deputy PM Karen Karapetyan assumed the position of acting prime minister. However, Pashinyan went a step further by demanding an interim transfer of power to him and his team. He would then organize competitive snap elections. The significance of this move for Armenian politics cannot be overstated. It effectively means the end of the ruling Republican Party machine, which has dominated the country’s politics for 20 years, since 1998. After three days of back-and-forth, the ruling party finally relented and declined to choose a nominee for the parliamentary vote on the interim prime minister on May 1, making Pashinyan the clear favorite. Meanwhile, Pashinyan solidified his position as the man of the moment by rallying supporters in the northern Armenian cities of Gyumri and Vanadzor. He also rallied supporters in his native Ijevan, where he was greeted by locals with traditional offerings of bread and salt.

Analysts outside of Armenia scrambled to make sense of the April Revolution. Was it a “color revolution” or a Ukrainian-style Maidan? Was it a “blow to Putin,” as the pages of the Washington Post suggested? The revolt did have certain elements that were recognizable in “color revolutions”—the street demonstrations, the involvement of youth, etc. However, its orientation was strictly domestic and its long-term causes—jobs, poverty, privatization, inequality, etc.—were entirely endogenous. Pashinyan and his supporters are mainly concerned about oligarchy and corruption, and Pashinyan himself continuously stresses the importance of Russian-Armenian relations. Given its security issues with neighboring Turkey and Azerbaijan, Armenia’s relationship with Moscow is unlikely to change, as Caucasus analyst Sergey Markedonov notes. On Sunday, in a “very warm” meeting with deputies from the Russian Duma, Pashinyan emphasized that Russian-Armenian relations will not be threatened but instead “deepened.”

It is true that the success of the Armenian demonstrators was applauded by prominent Putin critics like Aleksei Navalny, and Mikheil Saakashvili. Garry Kasparov, the chess champion and longtime Putin foe of partial Armenian background, even quipped that while one would love to throw Putin out of office, “the problem is [that] there aren’t enough Armenians in Russia!” Yet, at the same time, the Armenian civic activists were also praised by Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, who wrote that “Armenia, Russia is always with you!” In general, Russia acted with incredible caution, causing some in Armenia to joke that “the only thing that unites Navalny and Zakharova is a common love for Armenians!”

Ultimately, calling this movement a Maidan or framing it as an anti-Putin movement obscures our objective understanding of it as observers. In fact, the most recent demonstration is part of a long tradition of protest in Armenia dating back to the Soviet era. It began with the 1965 demonstrations in Yerevan on the 50th anniversary of the genocide, which resulted in the Soviet government’s construction of the Armenian-genocide memorial. This was followed in 1988-91 by the massive demonstrations to unite the Armenian exclave of Nagorno-Karabakh with then-Soviet Armenia during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika. These protests were massive and reportedly brought as many as one million people into the streets of Yerevan. Karabakh movement leaders, like the socialist activist Ashot Manucharyan, sought to keep the demonstrations peaceful and to guide them away from national chauvinism and provocations. These protests were followed by several more in the post-Soviet era, such as the protests against the Armenian presidential election results in 1996, 2008, and 2013, and the Electric Yerevan protests of 2015.

Although local, the April Revolution in Armenia has regional and even global significance. There are lessons in these protests, immediately for the peoples of Russia and the former Soviet Union, but also for all countries, including the United States. After all, in an era in which American democracy is being undermined by corporate plutocracy, what better response than to see civic activists in a country organize and mobilize against corruption, oligarchy, and nontransparent governance? In this way, Armenia is an example for peaceful civic activism not only for countries like Russia, Ukraine, or Azerbaijan, but for the United States as well.

All political forces in Armenia are now engaged in a national dialogue and it remains to be seen what will happen next in this fast-moving political drama. However, one thing is clear: Armenia’s April Revolution not only represents a major political change for the country, but also a psychological change for the Armenian people. No longer is there a prevailing sentiment of pessimism and defeatism, but of hope and empowerment. Armenian President Armen Sarkissian, who played a major role as a mediator between the sides, noted that the people are “courageous and proud.”

However, euphoria must be tempered by a healthy dose of realism. The process of implementing just change will take time and patience (“kamats kamats,” as the Armenians say). There is the risk of hopes being raised too high and being too easily disappointed. This moment is an enormous opportunity for real political and economic reform in Armenia, but popular enthusiasm and energy for change are not endless and the momentum must be maintained. Otherwise, the significance of the April Revolution will be lost.