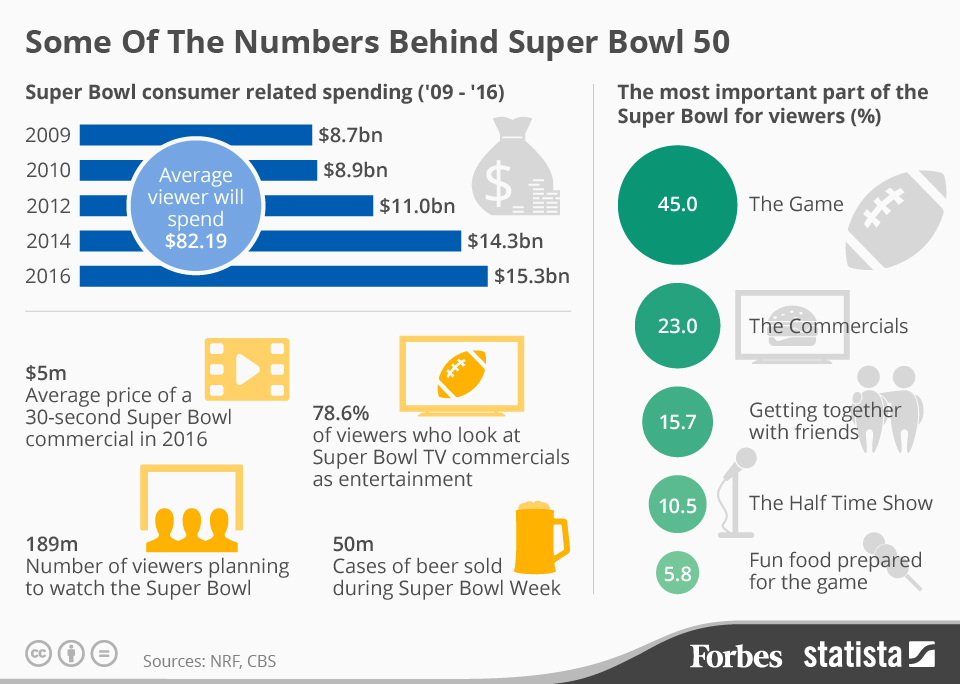

On Sunday, thousands will attend and millions will watch the Super Bowl, an event that has been used as a marker in measuring the size and even the success of other events: How many people are watching? How many pizzas got delivered? How much does a 30-second commercial cost?

Less known is the cost to the community that hosts the Super Bowl. While the NFL touts the game's economic success, many economists contend the figures are misleading and that the game results in much less benefit, or even a substantial cost, to the public. This is due primarily to the cost the host spends to build a state of the art facility – when the direct stadium proceeds go straight to the millionaire and billionaire club owners.

Routinely, the NFL or groups advocating for public financing of sport stadiums publish stories that put the economic impact on Super Bowl host cities in the hundreds of millions of dollars. But, “That conclusion is invalid,” said Roger G. Noll, emeritus professor of economics and co-editor of Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums.

“They interpret it as a net number as opposed to a gross number,” he said.

Case in point: this Sunday's ballgame. The state of Minnesota financed about 50 percent of the $1 billion U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, which opened in 2016. The NFL awarded Minneapolis the 2018 Super Bowl in 2014 after voters approved a measure allowing the state government to partially fund stadium construction.

The move follows a pattern that has grown in recent years. Since 2006, when Detroit hosted the Super Bowl, host cities have included Indianapolis, San Francisco (Santa Clara), and New Jersey (outdoor stadium). All of these cities were awarded Super Bowls based on their agreements to publicly finance new stadiums for the city’s NFL franchise.

Even traditional winter destinations like Arizona and Texas that have hosted Super Bowls built multi-million – or in some cases billion – dollar stadiums just prior to hosting. In 2015, the host city Glendale, Arizona lost money on the event, according to a report from azcentral.com. It should be noted that the NFL requires that cities, before hosting, agree not to charge sales tax on tickets or parking to the game as well as other NFL events leading up to Super Bowl Sunday.

Setting aside the economic impact from the game, those who support publicly financing new stadiums argue the stadiums provide long-term benefits such as property development and use for events other than football games. “If a stadium is part of a larger plan from a city to develop an area, it can uplift it, but [the stadium] has to be part of a larger plan not on its own,” said Professor Noll.

In 2009, when the new Yankee Stadium opened in the Bronx, nearby merchants contended that the new stadium with its added restaurants and merchandize stores siphoned business away from the restaurants and stores in the area. A 2017 New York Times articleshowed that the promised donations from the Yankees to people affected by the construction actually went to other parts of the Bronx that were not directly affected.

Other economic studies have shown that the economic impact is substantially less than the one claimed by supporters due to factors like increased spending on security and displacement of other visitors. For example, New Orleans has hosted the Super Bowl 10 times. When the Super Bowl coincides with the city’s Mardi Gras season, the effect is clear: Mardi Gras visitors are displaced by Super Bowl visitors, and there is no added tourism impact. Most of the hotels that house visitors are not local entities but large corporations, which funnel the proceeds back into the corporation’s coffers, not back into the local hotel and community.

Economic studies have also shown that the Super Bowl doesn’t lead to an increase in hospitality jobs in the long term. A 2010 studystated that while hotels charge three or four times their normal rate, that increase doesn’t trickle down to the hotel clerks, cleaning personnel or the wait staff.

Next year’s Super Bowl will be in Atlanta. Georgia has forked over $700 million to build a new stadium there, 25 years after the state provided $200 million for the Georgia Dome, which has been demolished. All this while the Atlanta Public School system furloughs its employees.

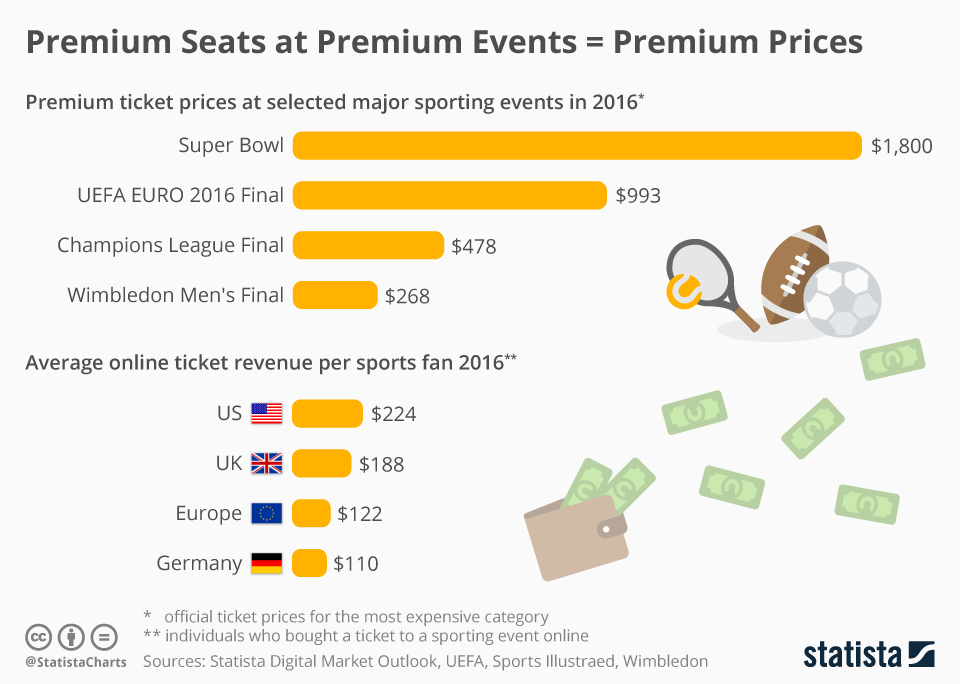

Perhaps doing what has become necessary to host a Super Bowl isn’t a matter of dollars and cents. Super Bowl tickets cost more than the average fan can afford. But paying for the seat licenses instituted by clubs for season ticket holders, as part of the financing for the stadium, didn’t deter many fans this year. As Minnesota can attest, all the Vikings' home games this year were sellouts.

As Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton said: “I’m not one to defend the economics of professional sports. Any deal you make in that world doesn’t make sense from the way the rest of us look at it.” Perhaps he is referring to the memories created, but those memories used to come much cheaper than they do now.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments