Although the wave of teachers’ strikes this past spring was inspiring, it was also inconclusive.

As schools reopen this month, unresolved issues will immediately resurface and teachers, who had the summer to organize, may be in an even stronger position to act than they were this past spring.

At the same time, the midterm elections have emerged as another domain of struggle. In most states, compensation for teachers and how to fund it will be major issues, while in some, most notably Oklahoma, teachers themselves are running for office.

What happens is anyone’s guess, but the table has been set for a school year and election season that, together, may have momentous consequences for education and workers for years to come.

Issues Remain Unresolved Following Spring Strikes

The first and most impressive walkout in 2018 happened in West Virginia, where teachers were able to shut down schools across the state for nearly two weeks, gaining significant concessions in compensation for themselves and other public sector workers. As part of the agreement with the state to go back to work, a task force was created to assess the all-important public sector health insurance system (PEIA), which had been raising fees steadily over the past few years, eating into the already low public sector compensation.

Major strikes also occurred in Oklahoma and Arizona and for many of the same reasons. In Oklahoma, the issues were the low pay and the degraded educational infrastructure. Images of dilapidated buildings and decrepit books made it into the national media and spoke volumes about education in that state.

The strikes ended after the state legislature agreed to increase compensation and funding for education, but that legislation only partially begins to address the longstanding funding shortage as well as pay and benefits. As an editorialist in the Oklahoma Observer wrote, “What teachers really want is r-e-s-p-e-c-t. They weren’t getting it. Now they’re demanding it.” Dozens have decided to run for office in state and local elections to do just that, expanding the struggle into the electoral arena.

In Arizona, similar problems were behind the week-long strike. The walkout ended with a commitment to increase teacher pay by 20 percent over three years as well as boost funding for the schools. But, as in other states, the funding mechanism is still unclear as is the prospect of future investments in education.

In addition to West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona, shorter or more limited strikes took place in Kentucky, Colorado, and North Carolina, again in response to long-term decreases in funding for public education and compensation for teachers.

In Kentucky, the two largest school districts – Louisville and Lexington – closed for a day as teachers from across the state rallied in large numbers at the state capital to increase funding after several years of cuts. In Colorado, ten school districts went on strike, while in North Carolina a one-day walkout for a large demonstration in Raleigh resulted in the closing of dozens of school districts across the state.

What Now?

In all of these states and many others, compensation for teachers and general funding levels for education remain the key issues. The spring 2018 agreements, while significant in some instances, only start to address resource deficits that have been accumulating over many years. Those resource problems persist. This is most obviously seen in Arizona and Oklahoma, both of which are experiencing teacher shortages as the school year begins.

In Arizona, thousands of less than fully-trained teachers are in classrooms this semester and, since the 2015-2016 school year, 7,200 teaching certificates have been issued to teachers “who aren't fully trained to lead a classroom." Despite the wage increases teachers have gained, there appears to be little if any improvement in the state’s ability to hire more fully-qualified teachers. Salaries still rank at or very close to the bottom among all states.

In Oklahoma, there are 500 vacancies statewide and the state is on pace to grant emergency certifications to a record number of teachers this year. School districts have also been forced to continue the practice of having administrators fill in as teachers at the beginning of the school year.

Much of the upcoming political drama surrounding teachers in all of these states will hinge on budgetary decisions and associated funding mechanisms. During the West Virginia strike in the spring, there had been significant contention about how to pay for the salary increases and fund the insurance program.

The teachers insisted that the additional funding should come from taxes on gas extraction, while conservative lawmakers preferred to shift funds from other public sector investments. At the moment, state officials have said that costs have been lower than expected and therefore funding looks secure through the 2019-20 school year.

The insurance funding issue may be something that can be put off for a while. But how to pay for salary increases is unclear and likely to be a point of contention in the fall. Teachers in West Virginia have been organizing, with a “legislative summit” held in the first week of September and plans to hold a state-wide rally Sept. 16.

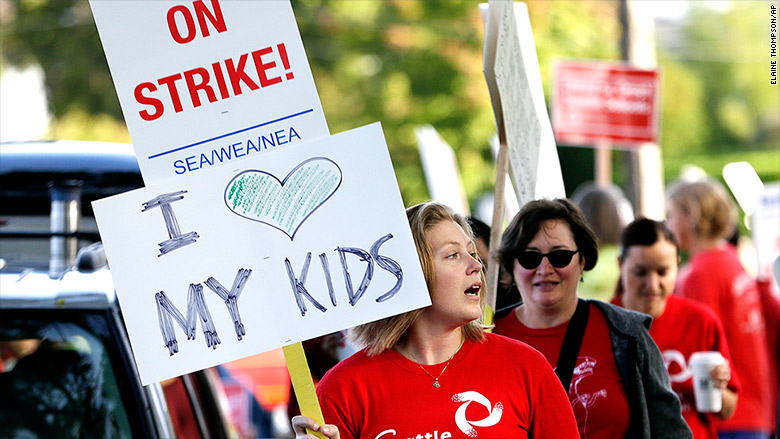

While many teachers and their unions in the major strike states are still in a watching and waiting mode, the revolt has spread. In Washington, where all school district budgets are being re-negotiated, a significant number of districts in the state have gone out on strike or threatened to do so.

In Seattle, teachers and other school employees authorized a strike for Sept. 5, but the teachers union and school officials reached a one-year agreement almost at the deadline.

That agreement was approved over the weekend by Seattle's educators, but uncertainties remain because of budget challenges and needed investments beyond teacher compensation.

In Colorado, there may be portents of teacher action as a major district in northeast Denver has moved to a four-day school week in order to address funding shortfalls.

And teachers in Los Angeles just voted to authorize a strike sometime in mid-October if contract talks are not successful. Here the main issues are reducing class size; less testing and more teaching time; new textbooks and other supplies; and restoring essential support structures that students need, including school nurses and guidance counselors.

Even in “deep blue” California, there have been significant cuts to education funding going back years. The state now ranks 43rd in the country in funding per student.

Beyond direct action by teachers and their unions, many have taken to the political sphere to make their case, with Oklahoma’s teachers leading the way. In an article with the electric headline “Oklahoma’s Teachers Just Purged the Statehouse of Their Enemies,” Eric Levitz reports that of 19 Republican lawmakers who opposed funding for teachers, only five made it through their party’s primaries, which ended just last week.

Major figures were defeated by, it must be emphasized, Republican insurgents favoring investments in education. All told, several dozen teachers in Oklahoma ran for local and statewide office. Most years, Oklahoma is not a state that gets much media attention during elections. But this year with teachers on the ballot, an uprising within the state Republican Party, and a competitive governor's race (hard-line pro-extraction Gov. Mary Fallin, who enjoys a cool 19 percent approval rating, is not running for re-election), Oklahoma will be an interesting state to watch, both for teachers’ advocates and progressives in general.

Propositions to fund education are also on the ballot in a few places. Bond issues totalling over $120 million are going before voters in 18 of Oklahoma’s school districts. Given statewide needs, the total is not impressive, but a few of the large districts are talking about significant sums – in the tens of millions.

No doubt, many districts cannot accomplish much on their own without significant support from the state, but the existence of those ballot measures indicates a broad recognition at the local level that something must be done, a recognition that may play out in the upcoming legislative and gubernatorial races.

In Arizona, after a 10-week canvassing effort, backers of the #InvestInEd initiative were able to put a major funding initiative, known as Proposition 207, on the ballot for November. Prop 207 would significantly increase taxes on wealthy individuals and families to pay for the additional funding that Gov. Doug Ducey agreed to in the strike settlement back in May.

But in a shocking turn of events in the last week of August, the state supreme court struck down the ruling, based on technicalities in the proposition’s language. That decision provoked the ire of many teachers who have held Ducey responsible because of his alliance with the Chamber of Commerce, his opposition to the measure, and the fact that he happens to have appointed three of the Court’s seven justices.

Ducey is up for re-election in November against progressive David Garcia and has been proposing to increase education funding by raising fees and taxes on the middle class instead of the wealthy. This controversy may help further tighten the race for the governor’s mansion.

The Broader Context: The Labor Struggle is Nationwide

These education funding and teacher mobilizations are closely connected to other political issues. The concerns articulated by all of the teachers’ strikes go back to funding and austerity imposed by state legislatures and associated tax breaks for wealthy individuals and corporations, particularly in extractive industries.

Teachers themselves have understood the broader context and have emerged as critical challengers to what Levitz calls the “red state model” – most notably pushed in Kansas by Gov. Kris Kobach with such devastating fiscal results that a significant number of Republican legislators helped override his veto of the budget bill.

It is also relevant that these teacher actions are coming in the context of the Supreme Court’s recent Janus decision, which held that public sector unions could no longer charge fees to non-union workers they were representing in collective bargaining with management. Without being able to collect these payments from non-union workers, unions are likely to lose a significant amount of funding, weakening their ability to organize and engage in political activities.

Will workers respond by becoming more militant and organizing more forcefully? This is a question that will be answered over the next months and years. In some cases, unions may lose significant strength and play an increasingly limited role representing worker interests. But in many other cases, as seen in the teachers strikes and other labor actions, worker militancy is growing.

Formal restraints on union activity and financial strength need not handcuff workers, who, as we have seen in the teachers strikes, are quite capable of organizing themselves outside the union if need be. Unions themselves have been doubling down on efforts to engage workers and get them to sign up.

This militancy may actually be extending to the general population as labor issues and unions get more attention. Teachers are perfectly positioned to educate the public about labor issues.

Everyone knows their children’s teachers and everywhere teachers strike, they make special efforts to communicate with parents and take care of “their kids” while schools are out. Seventy-three percent of Americans in a 2018 poll said they would support teachers in their community who went out on strike while 78 percent of Americans with children in public schools said they supported strikes. And in a just-released Gallup poll, support for unions nationwide was 62 percent, the highest in 15 years.

What happened in Missouri in August may tell us a lot about the inroads the unions have made in the public imagination. In a state with low union density and in a primary election, people voted by a two to one ratio to overturn legislation to make the entire state public sector “right to work.” The Missouri vote suggests that the Gallup poll might very well be underestimating public support for unions.

How all this plays out will have important political and economic consequences across the country. If teachers and their supporters remain militant and continue to gather public support, it will add a strong current to the already growing progressive movement and help push mainstream democratic politics to the left. Workers and their unions may begin to regain a substantial amount of the political heft they enjoyed in the middle of the 20th century.

But workers and unions must be strategic about how they build power. Going out on strike without first building near universal support is risky and organizing only through social media does not build the strong ties needed for effective solidarity to face the accumulating pressure of an extended strike. There are many opportunities for teachers and workers, but they must act boldly and strategically on contested terrain to achieve substantial gains.