There are two competing narratives about recent financial-reform efforts and the dangers that very large banks now pose around the world. One narrative is wrong; the other is scary.

At the center of the first narrative, preferred by financial-sector executives, is the view that all necessary reforms have already been adopted (or soon will be). Banks have less debt relative to their equity levels than they had in 2007. New rules limiting the scope of bank activities are in place in the United States, and soon will become law in the United Kingdom—and continental Europe could follow suit. Proponents of this view also claim that the megabanks are managing risk better than they did before the global financial crisis erupted in 2008.

In the second narrative, the world’s largest banks remain too big to manage and have strong incentives to engage in precisely the kind of excessive risk-taking that can bring down economies. Last year’s “London Whale” trading losses at JPMorgan Chase are a case in point. And, according to this narrative’s advocates, almost all big banks display symptoms of chronic mismanagement.

While the debate over megabanks sometimes sounds technical, in fact it is quite simple. Ask this question: If a humongous financial institution gets into trouble, is this a big deal for economic growth, unemployment, and the like? Or, more bluntly, could Citigroup or a similar-size European firm get into trouble and stumble again toward failure without attracting some form of government and central bank support (whether transparent or somewhat disguised)?

The U.S. took a step in the right direction with Title II of the Dodd-Frank reform legislation in 2010, which strengthened the resolution powers of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. And the FDIC has developed some plausible plans specifically for dealing with domestic financial firms. (I serve on the FDIC’s Systemic Resolution Advisory Committee; all views stated here are my own.)

But a great myth lurks at the heart of the financial industry’s argument that all is well. The FDIC’s resolution powers will not work for large, complex cross-border financial enterprises. The reason is simple: U.S. law can create a resolution authority that works only within national boundaries. Addressing potential failure at a firm like Citigroup would require a cross-border agreement between governments and all responsible agencies.

On the fringes of the International Monetary Fund’s just-completed spring meetings in Washington, D.C., I had the opportunity to talk with senior officials and their advisers from various countries, including from Europe. I asked all of them the same question: When will we have a binding framework for cross-border resolution?

The answers typically ranged from “not in our lifetimes” to “never.” Again, the reason is simple: Countries do not want to compromise their sovereignty or tie their hands in any way. Governments want the ability to decide how best to protect their countries’ perceived national interests when a crisis strikes. No one is willing to sign a treaty or otherwise pre-commit in a binding way (least of all a majority of the U.S. Senate, which must ratify such a treaty).

As Bill Dudley, the president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, put it recently, using the delicate language of central bankers, “The impediments to an orderly cross-border resolution still need to be fully identified and dismantled. This is necessary to eliminate the so-called ‘too big to fail’ problem.”

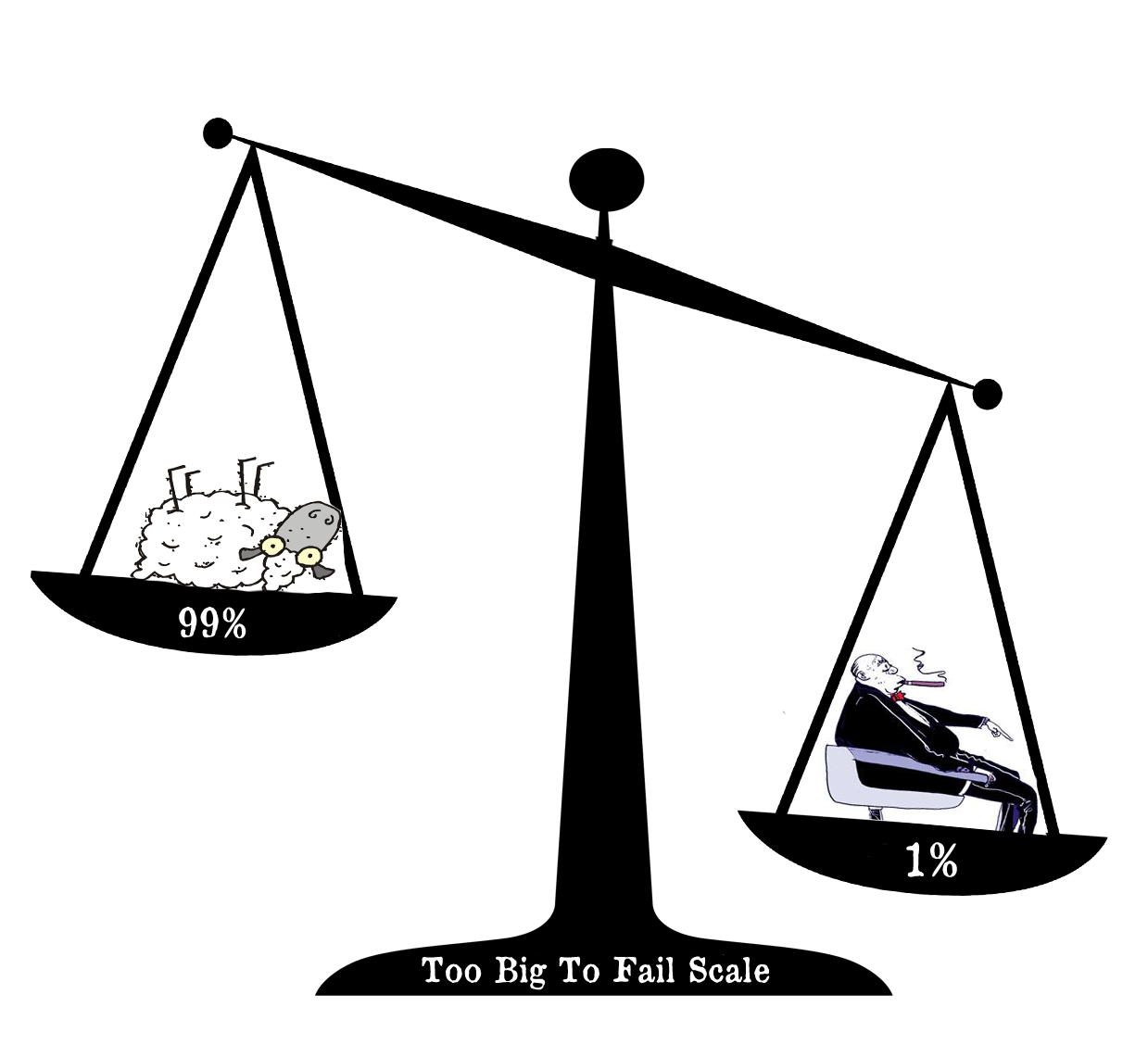

Translation: Orderly resolution of global megabanks is an illusion. As long as we allow cross-border banks at or close to their current scale, our political leaders will be unable to tolerate their failure. And, because these large financial institutions are by any meaningful definition “too big to fail,” they can borrow more cheaply than would otherwise be the case. Worse, they have both motive and opportunity to grow even larger.

This form of government support amounts to a large implicit subsidy for big banks. It is a bizarre form of subsidy, to be sure, but that does not make it any less damaging to the public interest. On the contrary, because implicit government support for “too big to fail” banks rises with the amount of risk that they assume, this support may be among the most dangerous subsidies that the world has ever seen. After all, more debt (relative to equity) means a higher payoff when things go well. And, when things go badly, it becomes the taxpayers’ problem (or the problem of some foreign government and their taxpayers).

What other part of the corporate world has the ability to drive the global economy into recession, as banks did in the fall of 2008? And who else has an incentive to maximize the amount of debt that they issue?

What the two narratives about financial reform have in common is that neither has a happy ending. Either we put a meaningful cap on the size of our largest financial firms, or we must brace ourselves for the debt-fueled economic explosion to come.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments