Last Wednesday, Federal bank regulators proposed to allow Wall Street more freedom to make riskier bets with federally-insured bank deposits – such as the money in your checking and savings accounts.

The proposal waters down the so-called “Volcker Rule” (named after former Fed chair Paul Volcker, who proposed it). The Volcker Rule was part of the Dodd-Frank Act, passed after the near meltdown of Wall Street in 2008 in order to prevent future near meltdowns.

The Volcker Rule was itself a watered-down version of the 1930s Glass-Steagall Act, enacted in response to the Great Crash of 1929. Glass-Steagall forced banks to choose between being commercial banks, taking in regular deposits and lending them out, or being investment banks that traded on their own capital.

Glass-Steagall’s key principle was to keep risky assets away from insured deposits. It worked well for more than half century. Then Wall Street saw opportunities to make lots of money by betting on stocks, bonds, and derivatives (bets on bets) – and in 1999 persuaded Bill Clinton and a Republican congress to repeal it.

Nine years later, Wall Street had to be bailed out, and millions of Americans lost their savings, their jobs, and their homes.

Why didn’t America simply reinstate Glass-Steagall after the last financial crisis? Because too much money was at stake. Wall Street was intent on keeping the door open to making bets with commercial deposits. So instead of Glass-Steagall, we got the Volcker Rule – almost 300 pages of regulatory mumbo-jumbo, riddled with exemptions and loopholes.

Now those loopholes and exemptions are about to get even bigger, until they swallow up the Volcker Rule altogether. If the latest proposal goes through, we’ll be nearly back to where we were before the crash of 2008.

Why should banks ever be permitted to use peoples’ bank deposits – insured by the federal government – to place risky bets on the banks’ own behalf? Bankers say the tougher regulatory standards put them at a disadvantage relative to their overseas competitors.

Baloney. Since the 2008 financial crisis, Europe has been more aggressive than the United States in clamping down on banks headquartered there. Britain is requiring its banks to have higher capital reserves than are so far contemplated in the United States.

The real reason Wall Street has spent huge sums trying to water down the Volcker Rule is that far vaster sums can be made if the Rule is out of the way. If you took the greed out of Wall Street all you’d have left is pavement.

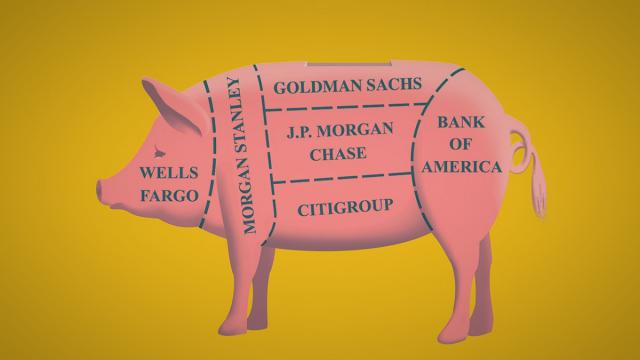

As a result of consolidations brought on by the Wall Street bailout, the biggest banks today are bigger and have more clout than ever. They and their clients know with certainty they will be bailed out if they get into trouble, which gives them a financial advantage over smaller competitors whose capital doesn’t come with such a guarantee. So they’re becoming even more powerful.

The only answer is to break up the giant banks. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was designed not only to improve economic efficiency by reducing the market power of economic giants like the railroads and oil companies but also to prevent companies from becoming so large that their political power would undermine democracy.

The sad lesson of Dodd-Frank and the Volcker Rule is that Wall Street is too powerful to allow effective regulation of it. America should have learned that lesson in 2008 as the Street brought the rest of the economy - and much of the world - to its knees.

If Trump were a true populist on the side of the people rather than powerful financial interests, he’d lead the way, as did Teddy Roosevelt starting in 1901.

But Trump is a fake populist. After all, he appointed the bank regulators who are now again deregulating Wall Street. Trump would rather stir up public rage against foreigners than address the true abuses of power inside America.

So we may have to wait until we have a true progressive populist president. Or until Wall Street nearly implodes again – robbing millions more of their savings, jobs, and homes. And the public once again demands action.