The Supreme Court on Tuesday turned back a challenge to a federal law that broadened the government’s power to eavesdrop on international phone calls and e-mails.

The decision, by a 5-to-4 vote that divided along ideological lines, probably means the Supreme Court will never rule on the constitutionality of that 2008 law.

More broadly, the ruling illustrated how hard it is to mount court challenges to a wide array of antiterrorism measures, including renditions of terrorism suspects to foreign countries and targeted killings using drones, in light of the combination of government secrecy and judicial doctrines limiting access to the courts.

“Absent a radical sea change from the courts, or more likely intervention from the Congress, the coffin is slamming shut on the ability of private citizens and civil liberties groups to challenge government counterterrorism policies, with the possible exception of Guantánamo,” said Stephen I. Vladeck, a law professor at American University.

Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. said that the journalists, lawyers and human rights advocates who challenged the constitutionality of the law could not show they had been harmed by it and so lacked standing to sue. The plaintiffs’ fear that they would be subject to surveillance in the future was too speculative to establish standing, he wrote.

Justice Alito also rejected arguments based on the steps the plaintiffs had taken to escape surveillance, including traveling to meet sources and clients in person rather than talking to them over the phone or sending e-mails. “They cannot manufacture standing by incurring costs in anticipation of nonimminent harms,” he wrote of the plaintiffs.

It is of no moment, Justice Alito wrote, that only the government knows for sure whether the plaintiffs’ communications have been intercepted. It is the plaintiffs’ burden, he wrote, to prove they have standing “by pointing to specific facts, not the government’s burden to disprove standing by revealing details of its surveillance priorities.”

In dissent, Justice Stephen G. Breyer wrote that the harm claimed by the plaintiffs was not speculative. “Indeed,” he wrote, “it is as likely to take place as are most future events that common-sense inference and ordinary knowledge of human nature tell us will happen.”

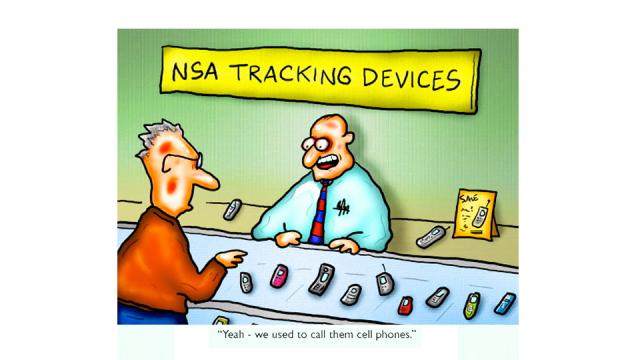

Under the system of warrantless surveillance that was put in place by the Bush administration shortly after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, aspects of which remain secret, the National Security Agency was authorized to monitor Americans’ international phone calls and e-mails without a warrant.

After The New York Times disclosed the program in 2005 and questions were raised about its constitutionality, Congress in 2008 amended the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, granting broad power to the executive branch to conduct surveillance aimed at persons overseas without an individual warrant.

The Obama administration defended the law in court, and a Justice Department spokesman said the government was “obviously pleased with the ruling.”

The decision, Clapper v. Amnesty International, No. 11-1025, arose from a challenge to the 2008 law by Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union and other groups and individuals, including journalists and lawyers who represent prisoners held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

The plaintiffs said the law violated their rights under the Fourth Amendment, which bars unreasonable searches, by allowing the government to intercept their international telephone calls and e-mails.

Justice Alito said the program was subject to significant safeguards, including supervision by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which meets in secret, and restrictions on what may be done with “nonpublic information about unconsenting U.S. persons.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony M. Kennedy and Clarence Thomas joined the majority opinion, and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan joined the dissent.

Jameel Jaffer, a lawyer with the A.C.L.U., said the decision “insulates the statute from meaningful judicial review and leaves Americans’ privacy rights to the mercy of the political branches.”

Justice Alito wrote that the prospect that no court may ever review the surveillance program was irrelevant to analyzing whether the plaintiffs had standing. But he added that the secret court does supervise the surveillance program.

It is also at least theoretically possible, he added, that the government will try to use information gathered from the program in an ordinary criminal prosecution and thus perhaps allow an argument “for a claim of standing on the part of the attorney” for the defendant.

Mr. Jaffer said the situations were far-fetched.

“Justice Alito’s opinion for the court seems to be based on the theory that the secret court may one day, in some as-yet unimagined case, subject the law to constitutional review, but that day may never come,” Mr. Jaffer said. In many national security cases, he added, the government has prevailed at the outset by citing lack of standing, the state secrets doctrine or officials’ immunity from suit.

“More than a decade after 9/11,” he said, “we still have no judicial ruling on the lawfulness of torture, of extraordinary rendition, of targeted killings or of the warrantless wiretapping program. These programs were all contested in the public sphere, but they have not been contested in the courts.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments