The Alameda County District Attorney's Office is leading a multi-agency effort to acquire a controversial cellphone surveillance device and has signed a non-disclosure agreement with the FBI and Harris Corporation, the maker of the equipment, prohibiting the DA from discussing or releasing information about the technology, according to documents we obtained.

Records also show that the Oakland and Fremont police departments are partnering with the Alameda County DA to acquire the device. The device, which costs approximately $535,000, is being purchased with federal homeland security grant funds and with funding from the DA and the cities of Oakland and Fremont.

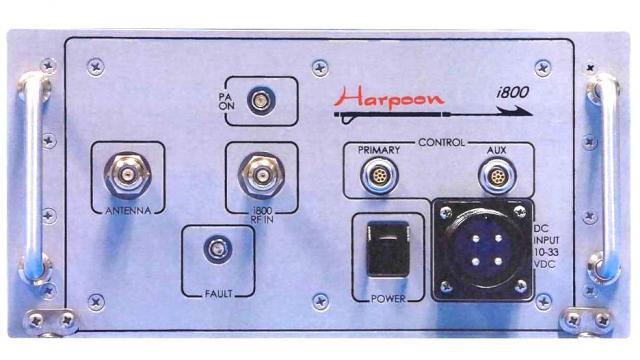

Florida-based Harris Corporation has a virtual monopoly on the so-called cell-site simulators, selling them under various brand names, including StingRay, KingFish, and Triggerfish. The Harris-made cell-site simulator being purchased by the Alameda County DA is called Hailstorm.

Cell-site simulators act as a police-controlled cellphone tower, forcing all phones in a geographic area to connect with them. In the process, the cell-site simulator collects unique identifying information from the target cellphones and allows police to pinpoint their location.

But civil liberties advocates have raised privacy concerns about the devices because they also collect data from the cellphones of innocent people within their reach. Brian Hofer, an attorney and civil liberties advocate crafting policies to address surveillance technology in Oakland, said the public has reason to worry about cell-site simulators. "A problem with this type of surveillance equipment is it operates in a dragnet fashion scooping up data from everyone in a given area," said Hofer.

A 2014 grant application that the Alameda County DA's Office provided to the Express states that the office, along with the Oakland and Fremont police departments, will make the technology available to all law enforcement agencies in the twelve-county region of the Bay Area. According to the grant documents, the device will "enhance Law Enforcement and Public Safety's ability to prevent, disrupt, track or locate terrorists or criminals, and reduce the search time and increase accuracy during Search and Rescue operations[.]"

The device is to be purchased with the help of a $180,000 grant from the Bay Area Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI), a multi-agency government authority that coordinates law enforcement agencies in the Bay Area and channels federal Homeland Security funds to them. The Alameda County Sheriff's Office administers the Bay Area UASI. The other $355,000 needed to buy the device will come from the District Attorney's Office and the cities of Fremont and Oakland.

A March 15, 2015 email from Craig Chew, assistant chief of the Alameda County DA's inspectors division, to colleagues at the Alameda County Sheriff's Office indicates that the DA's office has already received approval to spend Homeland Security grant funds on the Hailstorm cellphone tracker, and is waiting for federal approval of the non-disclosure agreement before finalizing the purchase. Chew's email also indicates that the DA's office has already been using Harris Corporation equipment.

"Just FYI, we are waiting [for] the NDA [non-disclosure agreement] to be approved by the FBI which should be any time at this point," wrote Chew. "We need this to be able to move forward. We have already shipped the old equipment back to Harris Corporation and they are just waiting for the NDA to be approved. They said as soon as they get that, things should move pretty quickly."

It's unclear which "old equipment" Chew was referring to, because the Alameda County District Attorney's Office has denied possessing a cell-site simulator. After being shown Chew's email, Alameda County District Attorney Spokesperson Teresa Drenick wrote in an email to us: "The inspectors division has not shipped any Harris equipment back, because the District Attorney's Office, including the inspector's division, does not now and has never owned Harris equipment."

Neither the Alameda County District Attorney's Office nor the Oakland Police Department have guidelines for how such devices are to be used by officers to track or eavesdrop on suspects, even though OPD has used a Stingray cell-site simulator since 2006. In response to a California Public Records Act request about whether the prosecutor's office had any policies regarding cell-site simulators, Drenick wrote, "[O]ur office has no current policies or guidelines for the use of this technology because we have never possessed it." Drenick also wrote that the DA's office is currently drafting a policy, but it will not be publicly available until the agencies acquire the device.

Cell-site simulators have also raised alarms because law enforcement agencies have apparently been using them without obtaining warrants and without informing defense attorneys about them. "We have not seen any discovery or material related to this technology in any of our cases," said Alameda County Public Defender Brendon Woods, in an interview. "It's terrifying to believe they could be using this information in prosecutions and not notifying defense attorneys."

Woods said that non-disclosure agreements governing the use of cell-site simulators coupled with the intentional obfuscation by law enforcement agencies make it almost impossible for defense attorneys to find out about the use of such devices. "If they're not disclosing this information, then we can't even get to the first question," he said.

Documents from the City of San Jose indicate that the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center, one of at least 72 intelligence facilities set up by the Department of Homeland Security after 9/11, has helped smaller police agencies in the region access cell-site simulators owned by Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose.

Last month, the investigative news organization Reveal disclosed a court battle between federal prosecutors and defense attorneys over the use of a StingRay by Oakland police to track down a group of people accused of shooting an Oakland police officer in 2013. Defense attorneys for the accused men allege that the cell-site simulator was used without a court order in violation of state and federal laws governing eavesdropping. A hearing on the admissibility of that evidence is scheduled for July 1.

According to documents regarding the San Jose Police Department's efforts to purchase a cell-site simulator from Harris Corporation, federal homeland security grants from Bay Area UASI were used to purchase the devices for police in Oakland and San Francisco. Evidence in the 2013 police shooting case currently working its way through federal court in San Francisco indicates that the Oakland police did not obtain a warrant to use their cell-site simulator. OPD spokesperson Johnna Watson said the agency does not have guidelines regarding the use of these types of surveillance devices.

The California Electronic Privacy Act — legislation that was approved by the state Senate last month and is currently in the Assembly — would require law enforcement agencies to obtain court orders before using electronic surveillance and tracking devices, including cell-site simulators. Similar restrictions have been approved by state legislatures in Washington, Utah, and Virginia.

A separate bill, SB 741, would mandate that cell-site simulators receive the approval of local legislatures at public hearings before they can be used by local law enforcement. SB 741, sponsored by Senator Jerry Hill, D-San Mateo, passed the state Senate unanimously in June.

Representatives of Harris Corporation declined to comment on the sale of Hailstorm equipment to the Alameda District Attorney's Office or the non-disclosure agreement.

Hanni Fakhoury, an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said there was "no doubt" that the Oakland Police Department has concealed the use of cell-site simulators for years. Pointing to annual management reports from 2007 through 2010 that reference the use of a StingRay by Oakland police, Fakhoury said the 2013 police shooting trial illustrated just how hard it is for defense attorneys to determine when the device was being used.

"Three words in the dispatch log, that's it," Fakhoury said, pointing to a line in a computer automated dispatch log made public in court filings that referred to the StingRay. "That's why nobody knows about it, because it's buried in records that are either redacted or they're very nebulous or vague about what's going on ... to a person that doesn't know to look for a stingray, that could be the phone company pinging the tower. It took the defense making a motion to reveal the truth, and I suspect that's how it has been in many other cases."

Linda Lye, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, said existing laws do not effectively address the privacy issues raised by mass surveillance devices like StingRays or Hailstorm. After reviewing documents regarding the 2013 Oakland police shooting case, Lye said it appears that law enforcement agencies have been using cell-site simulators under PEN register statutes. PEN registers authorize police, without a warrant, to collect telephone numbers, text messages, or data communication made from a particular telephone line or cellphone. Lye described PEN registers, which originally applied to landlines, as "more primitive" than cell-site simulators because the latter has the ability to precisely geo-locate people through their cellphones.

"Law enforcement agents are using these novel technologies and making up the rules as they go," said Lye. "Because there's so much secrecy surrounding these devices, there isn't a way for the courts to weigh in meaningfully or for the public to raise questions, or for legislators to build a statutory framework for their use."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments