In a precedent-setting case decided Monday by the New York Court of Appeals, local communities have triumphed over the fracking industry. The court ruled that the towns of Dryden and Middlefield can use local zoning laws to ban heavy industry, including oil and gas production within municipal borders.

“Today the Court stood with the people of Dryden and the people of New York to protect their right to self determination. It is clear that people, not corporations, have the right to decide how their community develops,” said Dryden Deputy Supervisor Jason Leifer.

“This would not have been possible without the hard work of many of my friends and neighbors and our lawyers Deborah Goldberg of Earthjustice and Mahlon Perkins. Today’s ruling shows all of America that a committed group of citizens and public officials can stand together against fearful odds and successfully defend their homes, their way of life and the environment against those who would harm them all in the name of profit.”

“This decision by the Court of Appeals has settled the matter once and for all across New York State and has sent a firm message to the oil and gas industry,” said Earthjustice Managing Attorney Deborah Goldberg. “For too long the oil and gas industry has intimidated and abused people, expecting to get away with it. That behavior is finally coming back to haunt them, as communities across the country stand up and say ‘no more.’ Earthjustice is proud to have stood with, and fought on behalf of, one such community.”

Many other cities and towns in New York have been waiting for today’s decision to establish bans or moratoriums of their own. The victory also gives legal authority to the more than 170 New York municipalities that have passed measures against fracking in their communities. Today’s decision will also serve as inspiration for a growing number of localities in Colorado, Ohio, Texas, Pennsylvania and California that are hoping to stop the controversial drilling practice.

“Town by town, New Yorkers have taken a stand against fracking. Today’s victory confirms that each of these towns is on firm legal ground,” said Helen Slottje, an Ithaca-based attorney whose legal research inspired New York’s local fracking ban groundswell and who was honored with the 2014 Goldman Environmental Prize.

“The oil and gas industry tried to take away a fundamental right that pre-dates even the Declaration of Independence: the right of municipalities to regulate local land use. But they failed. The anti-fracking measures passed by Dryden, Middlefield and dozens of other New York municipalities are fully enforceable.”

In response to the court’s 5-2 decision, John Armstrong of Frack Action and New Yorkers Against Fracking said, ”We applaud the court for once again affirming the right of New Yorkers to ban fracking and its toxic effects from their communities. As Chief Judge Lippman said, you don’t bulldoze over the voice of the people. But water and air contamination don’t stop at local boundaries, and Governor Cuomo must ban fracking statewide to protect our health and homes from the arrogant and inherently harmful fracking industry.”

The case in Dryden has attracted nation wide attention and taken on special significance. More than 20,000 people from across the country and globe sent messages to the town board, expressing support for the town through the course of its nearly three-year legal battle. An Earthjustice video depicting the town’s fight has garnered more than 80,000 views.

“We did it! This victory is for everyone who loves their town and will fight to the end to protect it,” said Dryden resident Deborah Cipolla-Dennis. “I’m proud of my town and I’m proud of the people in Fort Collins, CO; Denton, TX; Santa Cruz, CA; and all the others who are standing up to the oil and gas industry.”

Meanwhile, Ernie Atencio wrote this profile for High Country News about John Olívas, who led the charge to make New Mexico's Mora County the first in the U.S. to permanently ban corporations from fracking within its borders:

On a raw, bright winter day, John Olívas and his wife, Pam, hold court at the Hatchas Café in Mora, New Mexico. They seem to know everybody who comes in, chatting as they stamp snow off their boots and find seats. The street is lined with crumbling adobes and rusty pickups, and snowpacked pastures dotted with livestock and unused farm equipment stretch toward the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. There's not a fast food drive-through or big-box store in sight.

Olívas, a lean and youthful 43, is a longtime hunting guide and more recent wilderness advocate who was elected to the Mora County Commission in 2010. He lives in the house his great-grandparents built 200 years ago; his family was among the original settlers of the Mora Land Grant in 1835, when it was still part of Mexico. By local standards, that's not very long ago; many residents still speak the archaic Spanish that the original settlers brought to these mountain villages in the early 1600s.

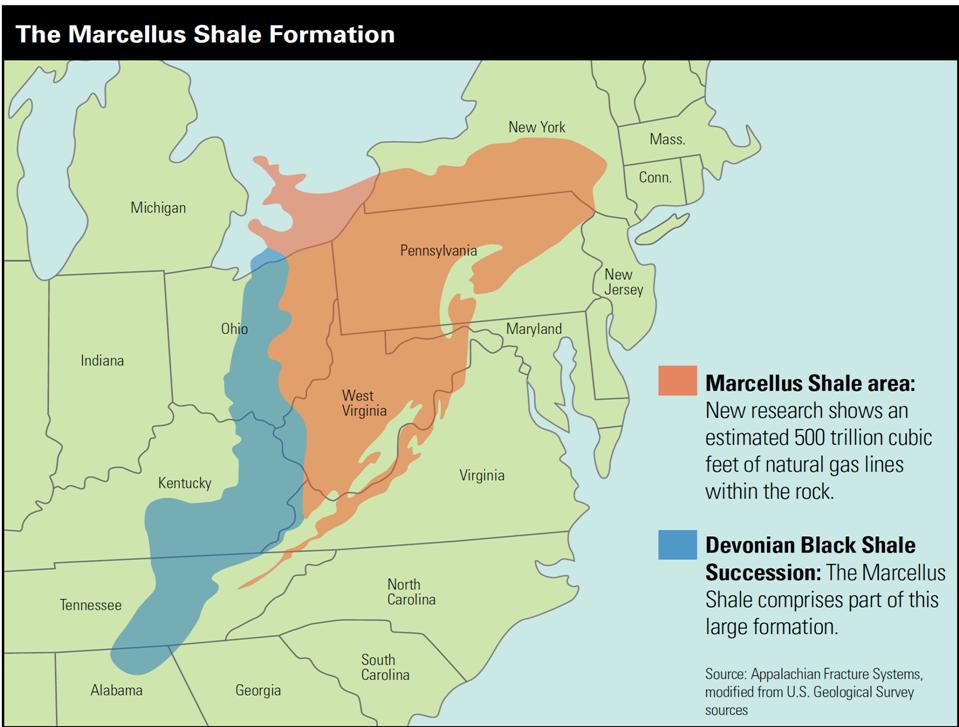

When I sit at his table, Olívas launches without preamble into a tirade against hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," which involves shooting a mixture of water, chemicals and sand deep underground to release oil or natural gas trapped in layers of rock. He worries that fracking and other aspects of oil and gas development will use too much water and pollute the other resources that this agrarian Indo-Hispano community needs. "We grow our own food. We burn our own wood," he explains. "People come to Mora for the landscape and the clean water and the clean air."

In April 2013, Olívas – modest and soft-spoken but ready for a fight – led the charge to make his county the first in the U.S. to permanently ban corporations from fracking or otherwise developing oil and gas within its borders. "A lot of people asked, ‘Who in the heck is this small community up in northern New Mexico that's picking a fight with oil and gas?' " he says. As a matter of survival, local people have always prioritized conservation, and they resent outside corporations making money at their expense, he notes. During six months of meetings, residents made clear that they want to protect their land-based heritage. "If you allow industry to come into your community, it changes the dynamics of the culture. I don't think we're ready for that."

Though Olívas acknowledges being "a product of industry" (his folks worked in uranium mines in Grants, across the state), childhood summers with his grandparents gave him a strong connection to Mora. "I used to spend hours out at the Mora River or the pond with my brother. My fondest memory is lassoing suckers." As a teen, after moving permanently to Mora, he went bow-hunting for elk alone in the peaks of the Pecos Wilderness. "That's where I think I got into the naturalist part of me. You'd go up there and you'd build a fire, you'd have to get wood, you'd have to do all the essentials of life."

Olívas built a successful career as a hunting guide and eventually got a master's in environmental science. But he never considered himself an environmentalist, largely because in a state that is one-half Latino, its green movement is overwhelmingly white. In the late '90s, environmental activists often came off as villains in racially charged fights over public-lands grazing and community access to firewood. Some were hanged in effigy at the State Capitol.

That tension has subsided, but Olívas, who joined the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance as a community organizer in 2008, is still often the only Chicano in the room. He serves as a bridge to build support for land-protection efforts, such as the recently designated Río Grande del Norte National Monument, making significant inroads with centuries-old farming and ranching land-grant communities, while fostering deeper respect for the local land ethic among urban, largely white environmental groups. As the father of four, he's proud that "those landscapes will be protected for my grandchildren and their grandchildren."

Where Mora's fracking ban is concerned, the work is just beginning: Four private landowners backed by oil and gas interests sued last November, followed by a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell in January, alleging violation of their constitutional rights. "We knew we were going to get sued," Olívas says, then repeats it with relish. Mora County plans to fight, with help from the Pennsylvania-based Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund and the New Mexico Environmental Law Center. Given opponents' deeper pockets, that could mean five to seven years of wrangling, and the creation of some legal precedents. However it ends, he says, "I definitely think we left our mark on the world." Other communities that have adopted similar measures – Las Vegas, New Mexico, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and more – are watching.

Olívas remains surprisingly calm. "I'm not losing any sleep," he says, finishing his coffee. Still, I sense he'd rather be hunting in the mountains he loves.

Originally published by EcoWatch

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments