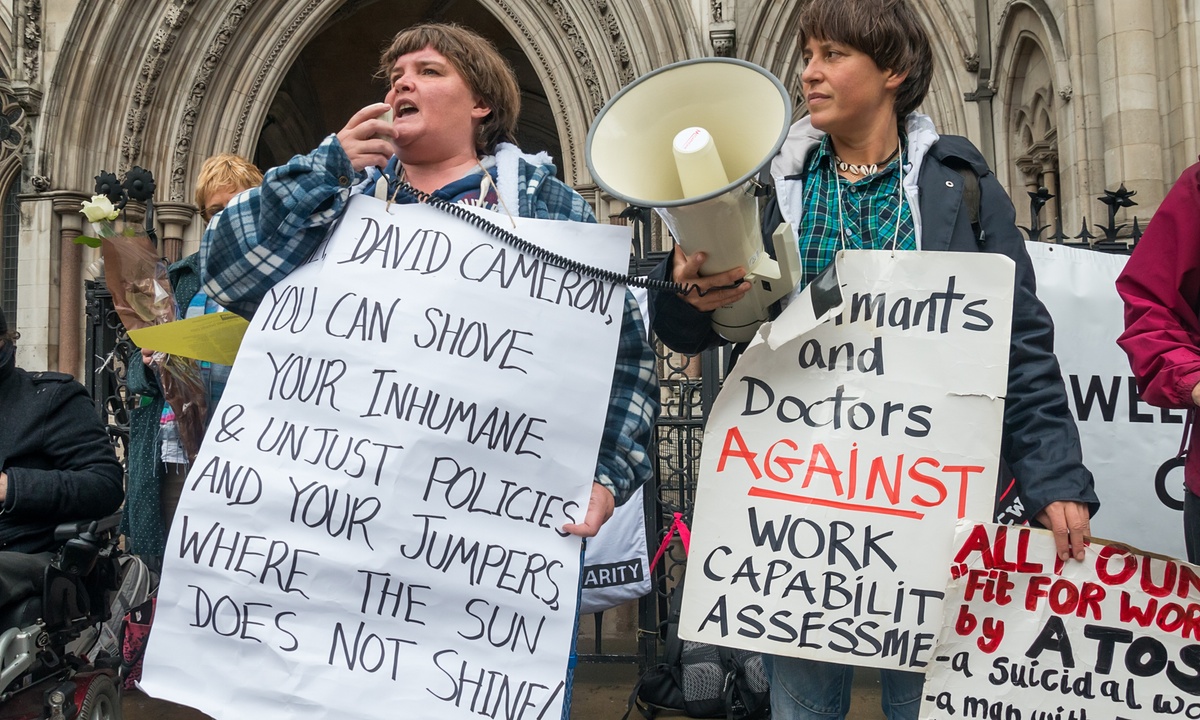

Between 2011 and 2014, more than 4,000 people deemed "fit to work" died within six weeks following their Work Capacity Assessment by the U.K.’s Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

The shocking revelations, which were only made public following a request under the U.K. Freedom of Information Act, revealed the stark dimensions of Britain's austerity regime and shed further light on the country's increasingly harsh attitude toward those suffering mental health problems.

In the summer, new figures emerged from ITV News showing that since 2010, a total of £85 million in funding cuts have reduced mental health provisions for children and young people across England. £35 million of those cuts have been made in the last year alone.

As a result, between 2011 and 2014 more than 2,100 mental health beds have closed, forcing patients to go hundreds of miles from their homes to get treatment.

This comes on top of vital funding cuts to mental health charities. Data from the mental health charity YoungMinds, for example, shows that two-thirds of local authorities in Britain have either frozen or cut their budgets in recent years. Those funding cuts are putting intense pressure on both staff and patients, as many existing wards are well over capacity with incidents of violence against mental health workers increasing.

According to the mental health charity Mind, it is estimated that one in 10 patients now have to wait longer than a year before they receive treatment through the National Health Service. This compares to "physical" illnesses, such as cancer and heart conditions, for which patients are typically treated within a few days.

Analysts have suggested that during Prime Minister David Cameron’s first five years in office, mental health trusts suffered a “real terms cut of 8.25% – the equivalent of stripping £598 million from their budgets.”

In response to the escalating crisis, the charity Change.org launched a petition, which now has more than 75,000 supporters, to urge Cameron to stop cutting young people’s mental health services and act on his promise of further funding.

Alarmingly, instead of pumping money that is so desperately needed into the mental health system, mental health trusts in England have forecast more significant cuts to their funding in the forthcoming years.

According to data obtained by the BBC, three-quarters of trusts show that from 2015-16 to 2018-19, mental health funding is expected to decrease by 8%. The figures are from a five-year plan compiled by 41 mental health trusts. Stephen Dalton of the Mental Health Network, which represents the trusts, told the BBC the figures are no surprise to mental health providers who've been “dealing with cuts to mental health services over the past five years," and that "there is an institutional bias against mental health services" in the country.

Alistair Burt, the government minister in charge of Britain’s mental health, admitted there is still a “postcode lottery” on the standard of care provided for those with mental health illnesses. Talking to ITV News, Burt said, “There are variations between populations and the like, and there are reasons for that variability. But outcomes should not vary so much. People should get a good quality of service everywhere, but some of the letters I see from MPs and their constituents tell me that isn’t the case. I’m worried about that.”

Some high profile cases involving the government’s treatment of people with mental health issues – particularly those receiving benefits – have caught national attention. One was the tragic incident of 44-year-old Mark Wood, who in 2014 was ruled "fit to work" despite being confirmed to have complex mental health conditions, and against the advice of his doctor.

Four months after his benefits were cut, Wood starved himself to death. In the wake of his death, Wood’s family called on the government to reform the way it treats people with mental health issues when assessing their eligibility to work. In the inquest into Wood’s death, his doctor said the Department for Work and Pension’s "Fit for Work" assessment was an “accelerating factor” in Wood’s decline and eventual death.

But Tom Pollard, policy and campaigns manager at the charity Mind, said that Mark Wood’s death is not an isolated case, and vulnerable individuals nationwide are struggling to “navigate a complex, and increasingly punitive, system.”

“We urgently need to see a complete overhaul of the system, to ensure nobody else falls through the cracks,” Pollard told The Guardian.

In the Department of Health’s policy paper concerning "Mental Health Service Reform," the government acknowledges that poor mental health is the largest cause of disability in the U.K., and that it is closely connected to other problems involving relationships and work prospects. The government’s views appear ironic, however, given the cuts to the mental health care system in recent years, the growing number of closures of mental health beds, and the prolific number of deaths of those with mental health issues who were deemed "fit to work."

A report released over the summer by the Care Quality Commission revealed that thousands of people in urgent need of mental health care received “inadequate support.” In response, Brian Dow, director of external affairs at the charity Rethink Mental Illness, said sympathy was what was needed first in order for Britain to address its mental health care crisis.

“We need a more sympathetic response: sympathy, understanding and good quality care when a patient walks in the door of A&E, and a sympathetic system where health and social care teams along with charities work in partnership to support the person properly after they are discharged.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments