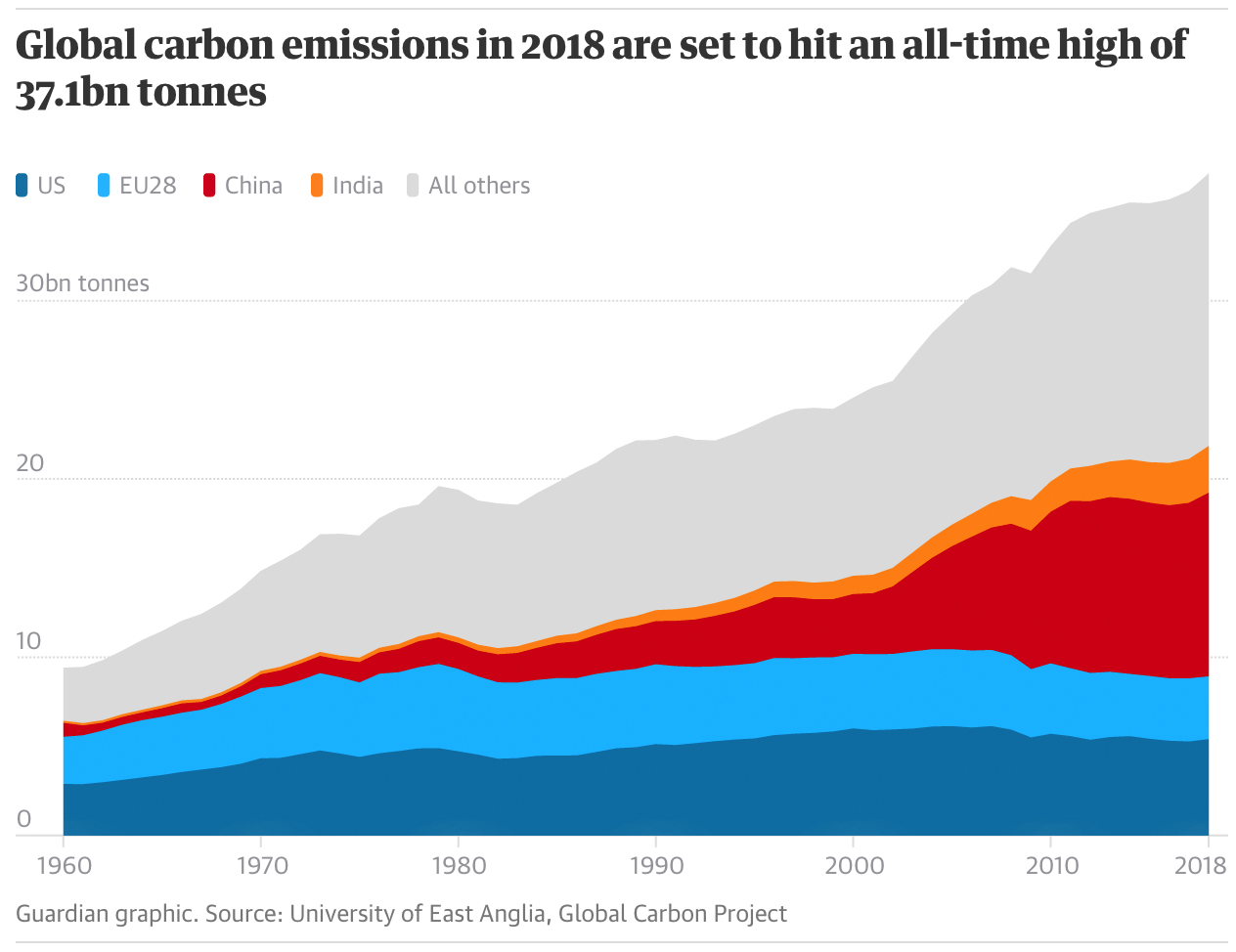

Global carbon emissions will jump to a record high in 2018, according to a report, dashing hopes a plateau of recent years would be maintained. It means emissions are heading in the opposite direction to the deep cuts urgently needed, say scientists, to fight climate change.

The rise is due to the growing number of cars on the roads and a renaissance of coal use and means the world remains on the track to catastrophic global warming. However, the report’s authors said the emissions trend can still be turned around by 2020, if cuts are made in transport, industry and farming emissions.

The research by the Global Carbon Project was launched at the UN climate summit in Katowice, Poland, where almost 200 nations are working to turn the vision of tackling climate change agreed in Paris in 2015 into action. The report estimates CO2 emissions will rise by 2.7% in 2018, sharply up on the plateau from 2014-16 and 1.6% rise in 2017.

Almost all countries are contributing to the rise, with emissions in China up 4.7%, in the U.S. by 2.5% and in India by 6.3% in 2018. The E.U.’s emissions are near flat, but this follows a decade of strong falls.

“The global rise in carbon emissions is worrying, because to deal with climate change they have to turn around and go to zero eventually,” said Prof Corinne Le Quéré, at the University of East Anglia, who led the research published in the journal Nature. “We are not seeing action in the way we really need to. This needs to change quickly.”

The current Paris agreement pledges from nations will only limit global warming to 3°C, while even a rise of 1.5°C will be disastrous for many people, according to the world’s scientists.

Le Quéré said: “I hope that by 2020, when [governments] have to come back with stronger commitments, we will then see a turning point.”

The International Energy Agency’s data also shows rising emissions in 2018. Its executive director, Fatih Birol, said: “This turnaround should be another warning to governments as they meet in Katowice this week.”

“Every year of rising emissions puts economies and the homes, lives and livelihoods of billions of people at risk,” said Christiana Figueres, at the Mission 2020 campaign, who was the UN climate diplomat overseeing the Paris agreement. “We are in the age of exponentials,” she said, with renewable energy and electric cars expanding rapidly, but with the extreme weather impacts of climate change doing the same. “We have to ensure it is the solutions exponential curve that is going to win the race.”

Prof David Reay, at the University of Edinburgh, U.K., said: “This annual balance sheet for global carbon is comprehensive and scientifically robust. Its message is more brutal than ever: we are deep in the red and heading still deeper. For all our sakes, world leaders must now do what is required.”

Harjeet Singh, at ActionAid International, said news of the emissions’ rise should galvanize those at the climate summit: “There’s way too much complacency in the air at these talks.”

The “dark news” of rising emissions is merging with two other alarming trends, according to Prof David Victor, at the University of California, San Diego, in an article with colleagues also published in Nature on Wednesday.

Falling air pollution is enabling more of the sun’s warmth to reach the Earth’s surface, as aerosol pollutants reflect sunlight, while a long-term natural climate cycle in the Pacific is entering a warm phase. Victor said: “Global warming is accelerating. [These] three trends will combine over the next 20 years to make climate change faster and more furious than anticipated.”

The Global Carbon Budget, produced by 76 scientists from 57 research institutions in 15 countries, found the major drivers of the 2018 increase were more coal-burning in China and India as their economies grew, and more oil used in more transport. Industry also used more gas. Renewable energy grew rapidly, but not enough to offset the increased use of fossil fuel.

“There was hope China was rapidly moving away from coal power, but the last two years have shown it will not be so easy to say farewell quickly,” said Jan Ivar Korsbakken, at the Centre for International Climate Research in Norway.

In the three years since the Paris agreement was signed, financial institutions have invested more than $478 billion in the world’s top 120 coal plant developers, according to a report by the NGOs Urgewald, BankTrack and partners. Chinese banks led the underwriting of coal investments, while Japanese banks led the loans, the NGOs found.

In the US, emissions rose as an unusually cold winter and hot summer boosted demand for both heating and cooling in homes. But it is expected that emissions will start to decline again in 2019, as cheap gas, wind and solar continue to displace coal – coal use has dropped 40% since 2005 and it is now at its lowest level since 1979.

The global rise in emissions, even in rich, developed nations, is very concerning, said Antonio Marcondes, Brazil’s chief negotiator at the UN summit: “Emission reductions are like credit-card debt: the longer they are put off, the more expensive and painful they become.”

Brazil reached its 2020 emissions targets early, but fears of a rise in deforestation under the new president, Jair Bolsonaro, could reverse this. But Le Quéré is optimistic that the rapid global rises seen in recent decades will not return: “This is very unlikely.”

Originally published by The Guardian