BERLIN – As French citizens headed to the polls on May 7 to cast their votes for president, tens of thousands of Europeans across the continent gathered in grand historic squares, quaint piazzas and cobblestone streets to send their French compatriots a clear message: “Let's stay together.”

For many of the demonstrators, who came together as part of an ongoing pan-European citizens initiative called Pulse of Europe, the face-off between France's far-right, ultranationalist Marine Le Pen and the Europhile centrist Emmanuel Macron was a moment of truth for the pro-E.U. protests they had been staging for months.

"We don't want to tell the French who to elect, but we want to show we care for them," said Michael Barth, a 44-year-old lawyer who helped established Pulse of Europe's Berlin branch. "France is an important partner on our side – if there is a 'Frexit,' that could mean the end of the E.U."

With the aim of preventing a repeat of events that led to the U.K.'s half-hearted embrace of Brexit, Pulse of Europe demonstrators took to the streets to urge French voters to elect a new president who was committed to the European project. "All these right-wing populists offer is just destruction with no plan for what's after," added Barth. "But we want to say the E.U. is worth preserving. It's one of the best achievements we've got, and it's worth fighting for."

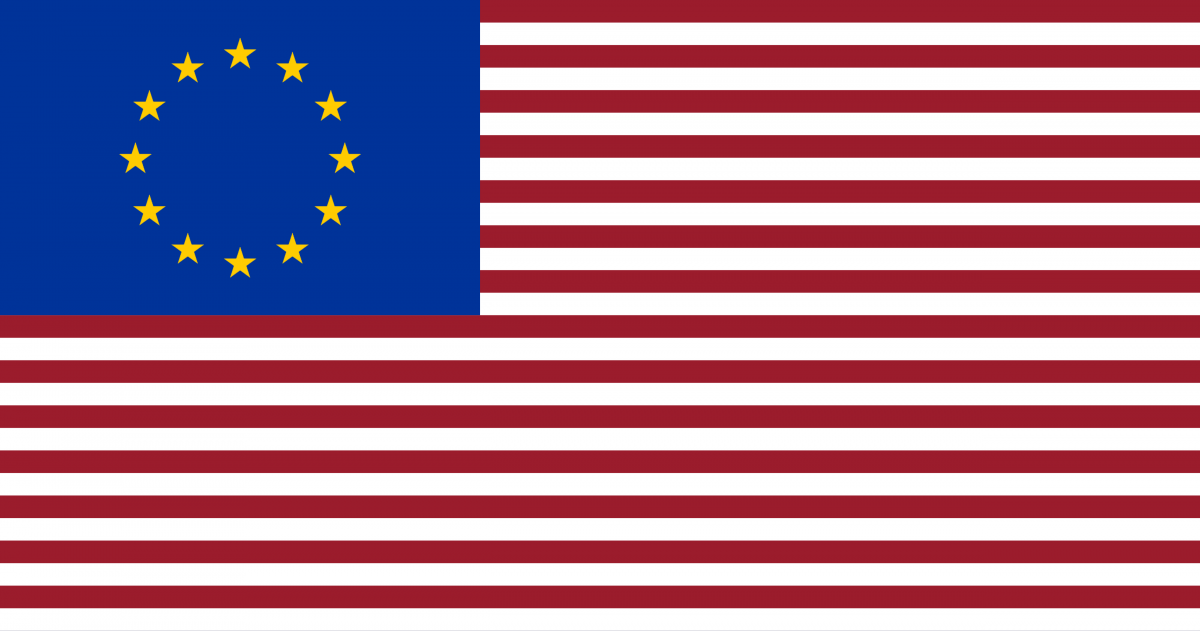

Waving the blue, star-spangled flags of the European Union and singing Beethoven's "Ode to Joy," the E.U. anthem, protesters have been coming for months to weekly demonstrations to show they care about the E.U.'s future. The impassioned protests come at a time when the continent is struggling to overcome crises ranging from the migrant overflow to Britain's impending withdrawal from the union.

"It's that dream of a 'United States of Europe,'" said Peter, a 53-year-old Austrian who has attended all 10 of the Pulse of Europe demonstrations held in Berlin since February. "People don't seem to know how precious the E.U. is."

Concerns over the growing strength of populist parties that want to tear the E.U. apart – like the far-right Freedom Party in his native Austria – keep bringing Peter back to Gendarmenmarkt, the famous square in central Berlin where the protests are held, he said.

"I don't want to see us return to nationalism," he said. "We're like a family. It's difficult at times but you can only solve these problems together."

Others said they came to Pulse of Europe because they like its positive atmosphere and the idea of demonstrating for a cause – in this case, the E.U.'s values and the freedoms it offers Europeans.

"I like that I can finally go out and protest in favor of something," said Doris, a Berlin-based pensioner who declined to give her age and last name. She and her husband, Sigi, have been to five Pulse of Europe demonstrations.

"We love to travel and want Europe to persist as it is," she said. "And I think it's great that so many others seem to feel the same."

A Movement is Growing to Save the E.U.

Roughly 3,000 other protesters join Doris and Sigi each Sunday on Gendarmenmarkt. Some 50,000 other protesters gather every week for the Pulse of Europe in more than 100 European cities in 16 countries, said organizers. Events are scheduled across Europe through September, when Germany holds parliamentary elections.

The brainchild of a Frankfurt-based lawyer couple, Daniel and Sabine Röder, Pulse of Europe began as an attempt to give a voice to pro-E.U. Europeans who felt as if Euroskeptic populists were drowning out their voices.

"The wake-up call was certainly Brexit, and also Trump," said Barth. "I don't want to be asked by my children one day, 'Daddy, what did you do when the E.U. fell apart?'"

Pulse of Europe held its first demonstration in Frankfurt last November before a crowd of 200. By February, rallies were being held in dozens of other cities in Germany – still home to the largest number of Pulse of Europe chapters – and beyond.

For many demonstrators, and even some organizers, it was the first time they had seriously engaged with a political cause.

"I'm not someone who usually demonstrates, but the way things are going, I feel like I have to do something," said Barbara Giegerich, a 36-year-old teacher attending her first Pulse of Europe protest in Berlin. "The ideas that the E.U. stand for – openness, solidarity, freedom – are ideas that are central to how I see myself."

Facing a pivotal series of elections in 2017 featuring Eurosceptic politicians like the Dutch populist Geert Wilders and France's far-right Marine Le Pen, who threatened the E.U.'s values and very survival, Pulse of Europe participants feel it is essential to display solidarity with the E.U.

They aren't alone. Support for European integration has remained relatively constant since the 1980s, said analysts.

"The vast majority of Europeans still support the E.U. and the European integration project," said Tanja Börzel, a professor of political science at the Free University of Berlin. "What has changed is that Eurosceptic forces on the right or on the left have been able to mobilize the 20 to 30 percent of Eurosceptic people in member states."

The significance of Pulse of Europe is that it's the first movement to successfully mobilize the "silent majority" of Europeans that support the E.U., she added.

"It's amazing to see how broad the spectrum is of people who march every Sunday," said Börzel. "It cuts across different age groups, social groups – a lot of different domains of civil society."

That mix of ages and backgrounds is reflected in the open mic portion of each rally, where audience members can grab the microphone and say why they support the E.U.

One Frenchman named Benjamin told the crowd he came to Gendarmenmarkt because Europe was "everything" to him and had made it possible for him to move to Berlin a year ago. A rally held in Berlin in March invited Franco-German couples to come on stage and share stories of how Europe helped them meet and fall in love.

With the catastrophe of a Le Pen victory in France averted, organizers are now reflecting on ways to maintain momentum going forward. While the group's founders have ruled out forming a political party to stay true to their origins as a nonpartisan, grassroots movement, Pulse of Europe could become something akin to a civil society organization like Greenpeace, said Barth.

"So if something happens where the EU needs support, like in Hungary where the government is clearly moving in an anti-E.U. direction, we can reactivate the network and get people out on the street to say this is going the wrong way and we don't want that," said Barth.

Organizers said they're amazed at the reception Pulse of Europe has found among Europeans and politicians. Some founding members have even been invited to meet with German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier, said Barth.

And some demonstrators say their first taste of activism for the French election has inspired them to carry on.

"We can't know the impact of our actions right away, but I'm convinced the effect will be felt down the line," said Giegerich. "I'll be back next Sunday."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments