The world's oceans are in a bad way, to put it mildly. Decades of overfishing, industrial pollution, plastic waste and threats to basic ecological stability posed by climate change all demonstrate how "humanity is collectively mismanaging the ocean to the brink of collapse," according to the World Wildlife Fund's Living Blue Planet Report released in September.

Now another threat is emerging: deep sea mining.

Seabed minerals were discovered as far back as 1873. But it's only within the last decade, as demand has grown for items such as smartphones – and as the depletion of inland resources has pushed mining exploration to further extremes – that technology has made the exaction of copper, zinc, manganese, nickel, cobalt and gold from under the sea possible.

Now, the world's first-ever commercial deep sea mining (DSM) project is due to start in under two years time – and environmentalists and scientists are worried.

“We currently have very poor understanding of deep sea ecosystems, few protected areas, and management regimes that are rudimentary at best,” said marine conservation biologist Rick Steiner. “Thus, the potential for irreversible ecological damage due to DSM is high. We need a ten-year continuous time series of research before we will have even a vague understanding of the environmental impact.”

Some action is being taken in the face of these uncertainties. In February, a team of researchers from 25 European institutions began a three-year study on the potential ecological effects of DSM. But it could be too little too late.

Mining in the Pacific

The Solwara 1 deep sea mine, located 19 miles off Papua New Guinea in the Pacific Ocean, is the first project in the world to be granted a commercial DSM extraction license. The application for the joint venture between Canadian mining company Nautilus Minerals and the Papua New Guina government was submitted in 2008. But due to an undisclosed equity dispute, the 20-year extraction license didn't get approval until last April.

Production is now expected to start in early 2018, and the company plans to mine deposits of copper, zinc and gold worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

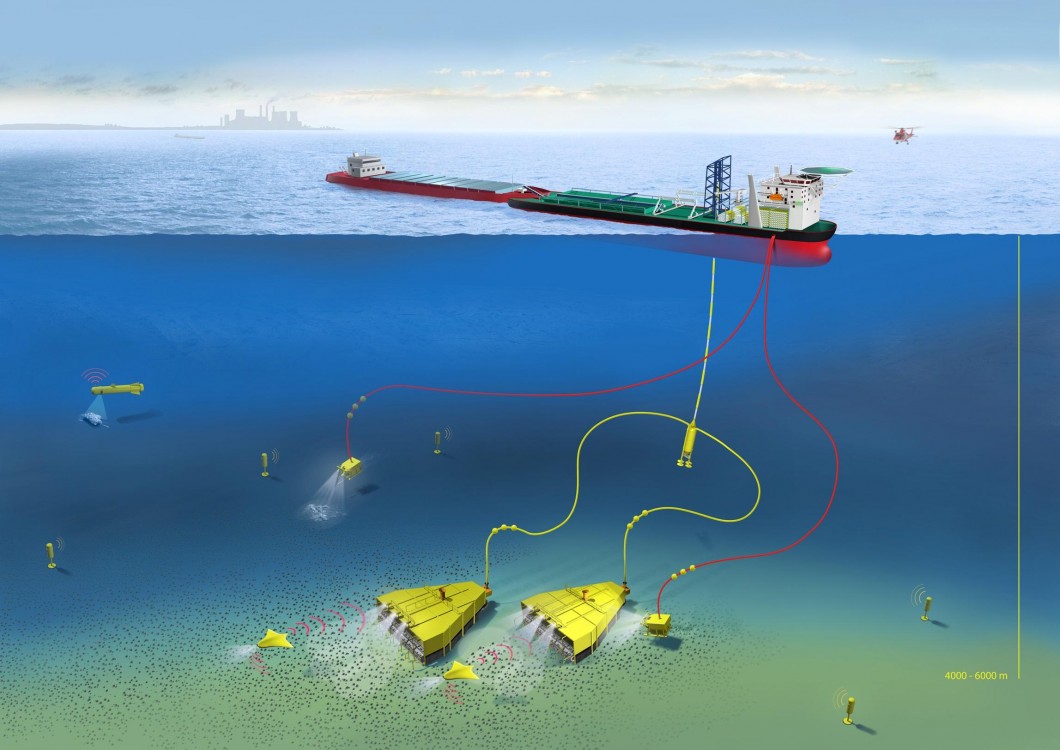

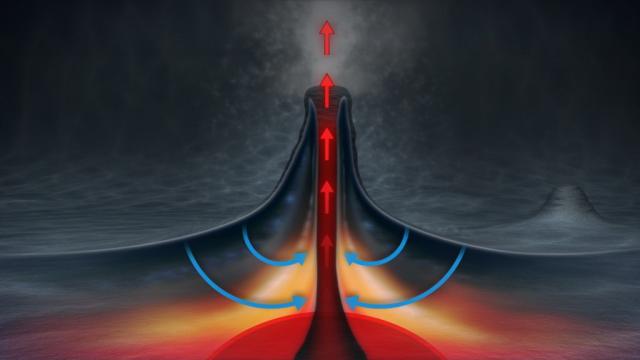

Responding to concerns about ocean health, Nautilus claims mining the seabed will have less of an impact than terrestrial mining due to the smaller scale of its operation – with DSM, minerals are found in concentrated nodules associated with volcanic activity – and the fact that no roads or infrastructure would be required to gain access.

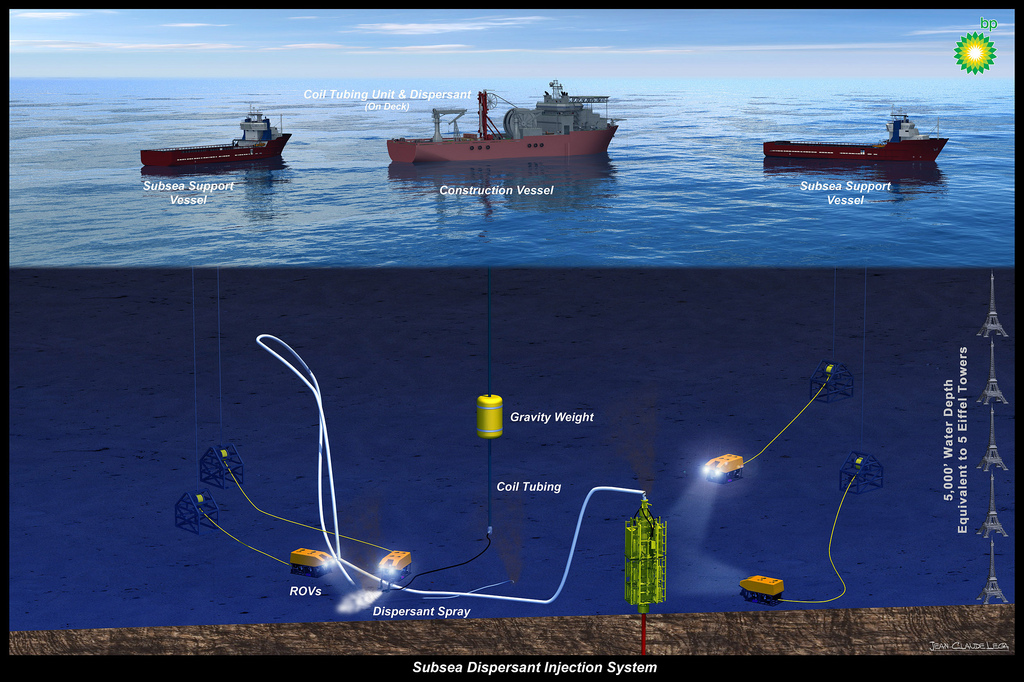

However, independent science-based reports released in 2009, 2011 and 2012 detail deficiencies in the science and modelling used by Nautilus. The reports claim that DSM could cause irreversible ecological damage to sites that could contain hundreds of species previously unknown to science. It also says the mining activity would introduce light and noise pollution in pristine areas, and could produce sediment plumes introducing toxic metals into the food chain – harming tuna, dolphins and potentially humans.

Opposition is Growing

The latest challenge to Solwara 1 has come from the Deep Sea Mining Campaign, which published a report in September entitled Accountability Zero that was endorsed by economists, scientists and NGOs including Greenpeace Australia and Earthworks. The group analyzed the results of an environmental impact report conducted by the American consultancy firm Earth Economics, and commissioned by Nautilus, which compared the potential impacts of Solwara 1 to existing land-based copper mining. Accountability Zero claims the report failed to account for the unique social, cultural and economic values of oceans.

And it's not just oceanographers and NGOs that are concerned.

Despite Papua New Guinea's government ignoring a 24,000-strong petition that calls for a stop to experimental seabed mining, opposition to DSM from the country's citizens continues to grow. In 2008, the Bismarck Solomon Seas Indigenous Peoples Council was formed with the specific aim of opposing Solwara 1. Papua New Guinea Mine Watch is also calling for Pacific Ocean mining to stop, and there is an ongoing petition urging Pacific leaders to take a cautious approach to DSM.

“Never before in Papua New Guinea’s history has a development proposal galvanized such wide-ranging opposition,” said Dr. Helen Rosenbaum, coordinator of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign, "from students and church leaders – in 2013 the Pacific Conference of Churches passed a resolution to stop all forms of experimental seabed mining in the Pacific – to NGOs, academics, and national and provincial parliamentarians.”

Setting a Precedent

Solwara 1 is currently the only DSM project with a commercial operating license, but many others are waiting to follow in its footsteps.

The number of companies seeking to mine in international waters has tripled in the last four years, and the U.S., UK, Russia, China, Japan, Brazil, Germany and South Korea all have exploration projects underway. Most of these are in the Pacific, while others are in the Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Separate projects have also been proposed in the national waters of Fiji, the Cook Islands, Tonga and New Zealand.

The process regulating DSM is distinct. Permits to explore for minerals are issued by governments within their territorial waters – 200 nautical miles from shore – or by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in international waters.

Formed in 1994, the ISA was established by the UN to regulate international waters, described as “common heritage of mankind” and not subject to direct claims by sovereign states. But a major criticism of the ISA has been the issuance of exploration permits without having first approved environmental standards.

Despite issuing mining permits since its inception, it wasn't until July that the ISA finally brought together representatives from its 170 member states to began drafting a framework on environmental standards and regulations, which is expected to be finalized late this year at the earliest.

In the lead-up to July's meeting, a policy paper published in Science called for the ISA to cease issuing permits until environmental controls are in place. Written by researchers from the Center for Ocean Solutions and co-authors from leading global institutions, the report proposes a strategy for balancing commercial extraction with protection for seabed habitats.

But despite the paper's warnings, the ISA went ahead and authorized the latest Pacific exploration contract to China Minmetals. Altogether, the ISA has issued 27 permits for mineral exploration covering around 1.2 million square miles of seabed. All but eight have been issued within the last four years.

Building International Support

With the surge in exploration permits has come a gradual but growing international movement against DSM.

At the 2012 Rio+20 conference in Brazil, a Fiji-based women's NGO marched with an anti-DSM message, and in 2013 the Namibian government issued a moratorium on all deep sea exploration within its waters until a long-term impact assessment is made. International campaign groups including Greenpeace and the Yes to Life, No to Mining movement have issue statements against DSM.

In the U.S., the Center for Biological Diversity is going further and taking legal action. In May, the organization launched a lawsuitagainst the government over its approval of the first-ever large-scale DSM exploration project between Hawaii and Mexico, claiming it lacked the required environmental assessment.

New Zealand is another country where anti-DSM campaigning has been strong due to the government’s 2004 Foreshore and Seabed legislation, which created a series of prospecting permits for companies seeking to exploit the iron sand reserves in the west coast seabed.

As a result, the community-based action group Kiwis Against Seabed Mining (KASM) was established in 2005 to protest DSM, and its biggest victory to date came against Trans Tasman Resources in December of last year. TTR wanted to mine 50 million tons of iron sand from the seabed, but was rejected by the country's Environment Protection Authority.

The company planned to appeal, but withdrew following an overwhelming response from people opposed to the proposal, including 5,000 submissions from local citizens. The victory showed that DSM projects could be overcome. But in New Zealand and elsewhere, many see the public and civil society response still lacking.

“To date seabed mining has been very much under the radar but it absolutely warrants a lot more attention,” said Phil McCabe, chairman of KASM. “Greenpeace has stated that seabed mining has the potential to have the largest areal impact on the planet of any human activity – it’s akin to deforestation on a massive scale, and we need to turn people on to [what it is].”

An Avaaz petition calling for a moratorium on seabed mining prior to the ISA's July meeting failed to reach its target, falling 7,000 signatures short of its 80,000 signature goal. But it demonstrated how close the anti-DSM movement could be to galvanizing widespread awareness and support. The question is: with so many mining proposals already underway and a lack of legislation protecting the deep sea, will the opposition come too late?

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments