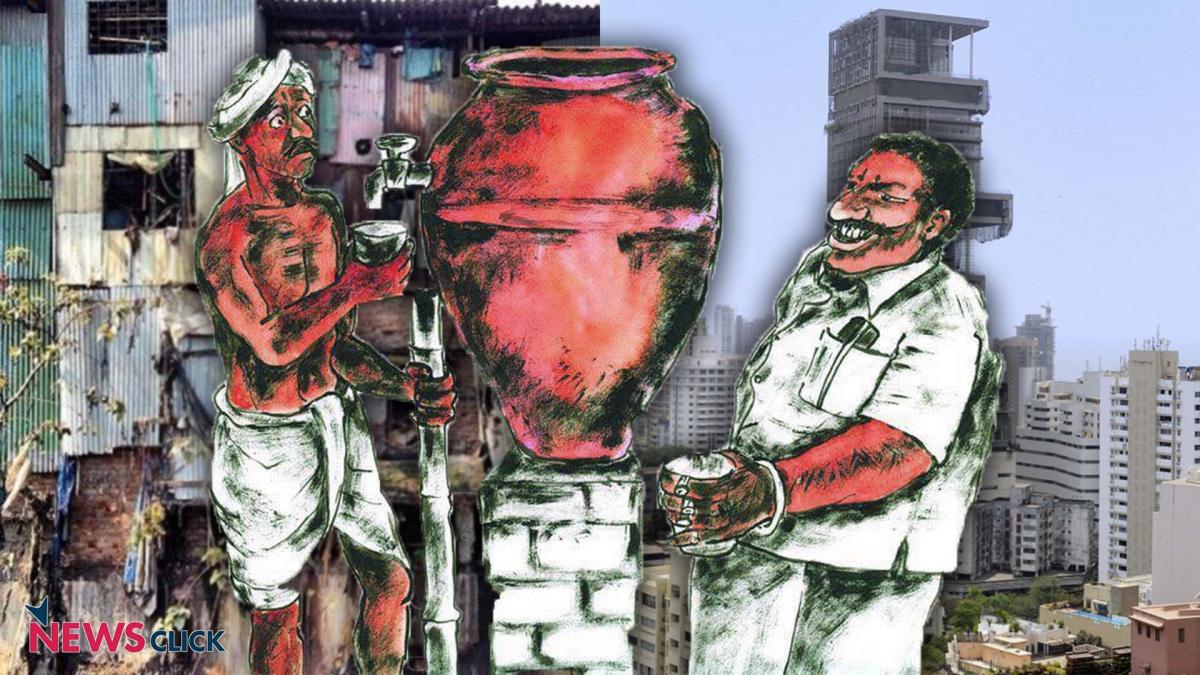

Illustration by Robert G Fresson

This is the sixteenth installment in a series about extending the Green New Deal to confront multiple global crises. Read Part I (Deconstructing environmental racism), II (Rural renewal), III (Upcycle the war machine), IV (GND manifestos), V (No oil bailouts), VI (No corporate ecocide), VII (Defund the police), VIII (Zero Covid approach: NZ), IX (Finnish equality lessons), X (Denmark stops drilling), XI (Costa Rica rewilding), XII (Indigenous justice), XIV (No borders) and XV (Chile's democratic revolution).

The dream of freedom is central to our dominant economic system. But, in reality, it incurs a nightmare. Freedom is narrowed down to the promise of freedom to consume: what you want, when you want, packaged in plastic, delivered to your door. This freedom harms people and the environment, and ultimately our choices are limited by corporate monopolies selling us mass produced stuff that breaks.

Freedom based on consumption plays into the hands – and fills the often offshore bank accounts – of billionaires. It empowers those elites, making them seem valuable to our economy. The idea that billionaires make the economic system function has become so prevalent, many consider it common sense.

Spaceships and astronomical inequality

Few people better encapsulate global power and wealth inequality than Jeff Bezos and his recent private space flight. After landing, Bezos casually told his Amazon workers and customers: “You guys paid for all this.”

Yet to Bezos’s likely surprise, while he was up in space his employees were busy organizing a union.

Even at Amazon – a company that embodies the hyper-neoliberal, precarious model of work in the 21st century – workers are fighting back. This is essential, yet more struggle is necessary.

Sometimes, billionaires’ wealth and influence manages to get questioned, if not scrutinized – for instance, when Elon Musk bought Twitter last month, or in the multi-layered billionaire character portrayed in the film Don't Look Up, a perfect embodiment of Musk, Bezos, Gates and their ilk.

It is widely considered sensible that governments must support corporations like the big banks – and that if they fail, we all fail. Likewise, it is widely accepted that corporations need property rights. Covid vaccines are just one example in a long list of products and innovations bankrolled by state investment, proving that the triumph of private entrepreneurialism is often a fallacy.

No wonder perhaps that Bill Gates is leading a supposedly philanthropic scheme to manage global vaccines, which protects Big Pharma's intellectual property rights with the overarching message not to question them. In the end, Microsoft created its platforms from state-sponsored innovation.

This belief in entrepreneurialism for its own sake is one of the ideas behind neoliberalism: a system of power widespread yet little understood beyond academics on the Left. A parallel can be drawn to the way that few people throughout history have questioned – much less challenged – the power of the Roman Catholic church or monarchy. Of course, more people question these institutions openly today, yet they still hold a great deal of sway in our society, our economy and our politics.

Disempowering neoliberal ideas must be central to realizing a green and just future. To do this it is worth looking at where neoliberal ideology actually came from. Here there are pointers for how to undermine it.

When neoliberalism was new

Neoliberal influencers today are found across the media. Often we hear from think tank mouthpieces who are presented as experts. These people also have water-tight connections to, and sway over, politicians, and as speakers on your TV set, they rationalize everything from climate denial and deregulation to tax cuts and privatization.

The common ancestor of this diverging and divergent network of old boys' neoliberal think tanks is the Mont Pelerin Society, founded in Switzerland with leading neoliberal pioneers including Friedrich Von Hayek and Milton Friedman. Friedman was associated with the Chicago Boys, whose ideas were first tried when neoliberalism was violently forced on the people of Chile following the CIA-backed coup that took down the country’s democratically elected leader, Salvador Allende.

One might imagine all think tanks were dreamed up, sponsored, then put into action by corporate billionaires, using violence and political power to then spread their ideas around the world. But this is a bit simplistic.

The first neoliberal thinkers really believed in what they were doing. They did not all come from the most privileged backgrounds. For example, Friedman was second-generation working class, while Margaret Thatcher, Britain's first neoliberal prime minister, was a self-celebrated green grocessor's daughter.

Based on original documents, Professor Jessica Whyte, in her book The Morals of the Market: Human Rights and the Rise of Neoliberalism, explores how the founders of Mont Pelerin Society genuinely believed they were acting on a moral mission (moral by their own standards at least).

After WWII, the neoliberals self-appointed themselves to save the world. Yet their worldview was regressive: they wanted to return to the social order of empire, a world divided and ruled by racism, patriarchy and class division. Yet as Whyte points out, theirs was not an amoral vision aimed at creating a world based on endless growth run by technocrats working for business elites.

What Whyte tells us is how neoliberals packaged economic ideas like regulation and low taxes with a moral argument. The neoliberals rejected the idea of social welfare and political engagement, instead pushing notions such as individual freedom, family values and personal responsibility.

This analysis helps reveal why neoliberals and the Christian Right have, in recent decades, fallen into such an easy marriage. Further still, Whyte's research shows how neoliberals were able to wrap their message around the idea of rights – creating an ideology all about freedom, which ultimately only empowered the super-rich.

Crucially, the Mont Pelerin Society arose in 1947, the same year as the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The neoliberals were successful in co-opting this new dialogue: turning rights and by extension freedoms into the right to consume, based on our individual rights.

One success Whyte highlights about the neoliberals’ project is the way many worldwide NGOs swallowed the whole discourse starting in the 1980s. Organizations whose supposed raison d'etre was to support people in the Global South completely lost touch with any critique suggesting that politics or history or imperialism had caused peoples' chronic poor circumstances.

Instead, many NGOs were supporting people to individually work away from poverty. There is nothing more political than convincing others to take an apolitical approach. This supports the status quo, so nothing gets questioned.

Another world is collective

Of course it is still the case that billionaires have pumped proportions of their wealth into neoliberal think tanks and lobby groups. Not every supporter of neoliberalism is a true believer in trickle-down, or in the twisted moral logic of the market. Yet what does this mean for breaking neoliberalism's spell and pushing new political arrangements such as the Green New Deal?

Firstly, we need to recognise that the GND has to be political, and not fall into apolitical nihilism. That is, it needs to be explicitly about decolonising politics and about deconstructing existing power relations, including elevating the rights of women, people from the Global South and people of colour, working class, migrants and so on.

Thirdly, the neoliberal project's largest impact – alongside its absolute destructive power and how it has enriched the few against the many – is how it has shattered the Overton window.

What was considered mainstream, for instance in the US, UK or other countries in the 1960s, is no longer widely held as common sense. Examples include welfare that provides a comprehensive safety net, universal access to public services, people’s rights being protected against corporate excesses, and more.

To alter course, we need to delve deeper into the idea of freedom and rearticulate the fact – expressed so eloquently decades ago by Martin Luther King Jr. – that no one is free until everyone is free. We need to ask what choice and what freedoms there will be in a neoliberal future defined by even worse degrees of climate change and ever-increasing corporate power.

All these ideas are wrapped up in a vision for a green and socially just future. But they need to be presented front and center to overcome the individualized nightmare in which we still collectively live.

Read Part I (Deconstructing environmental racism), II (Rural renewal), III (Upcycle the war machine), IV (GND manifestos), V (No oil bailouts), VI (No corporate ecocide), VII (Defund the police), VIII (Zero Covid approach: NZ), IX (Finnish equality lessons), X (Denmark stops drilling), XI (Costa Rica rewilding), XII (Indigenous justice), XIV (No borders) and XV (Chile's democratic revolution).