The devastating videos of Tyre Nichols’ fatal beating at the hands of police officers in Memphis, Tennessee have re-ignited the national conversation about police terror in the United States. But if America truly hopes to make sure no one else has to endure what Nichols went through, the conversation needs to go further than new or different law enforcement training.

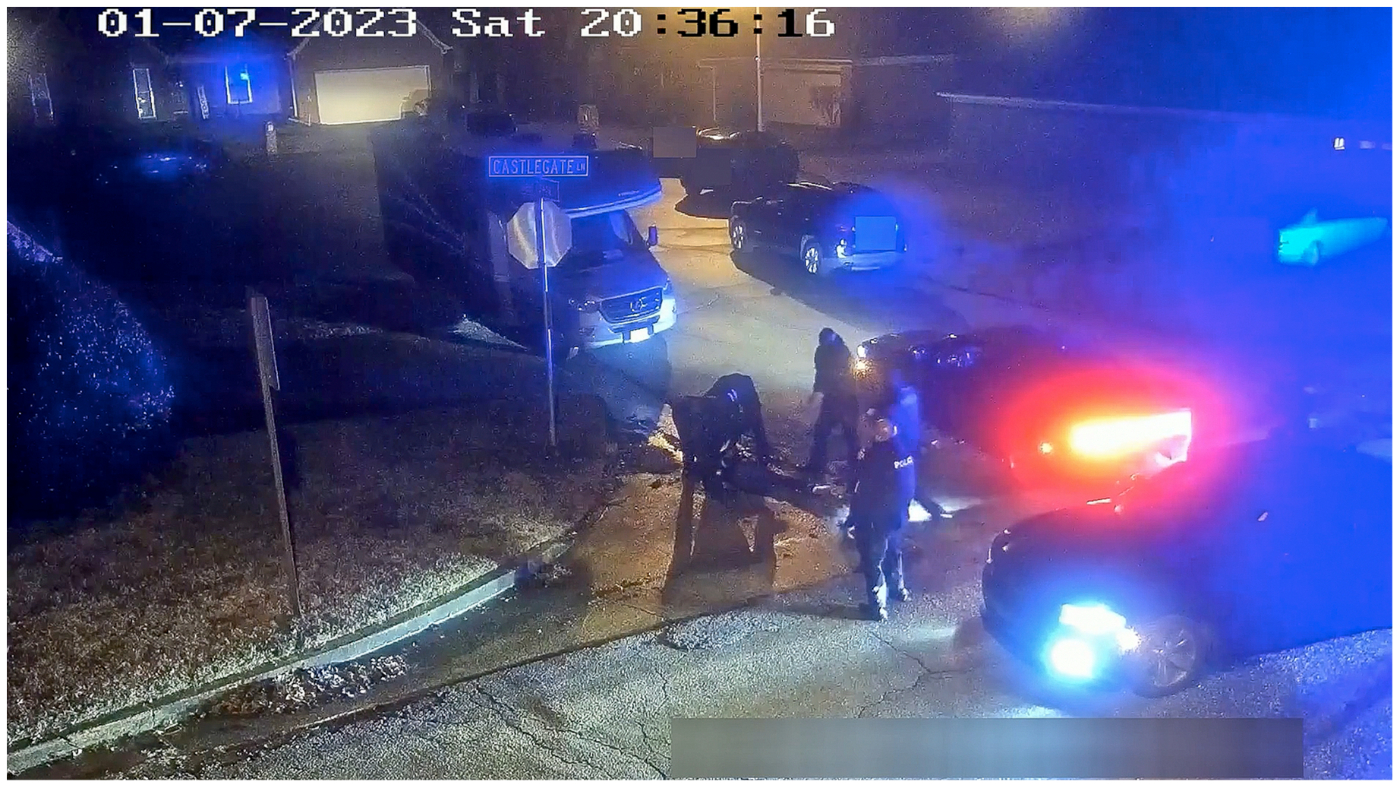

On its face, justice for Nichols appears to be far swifter than in similar cases: Even before the body camera video of the beating went public, five of the officers in the beating – Taddarius Bean, Demetrious Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills Jr., and Justin Smith – were fired and charged with second-degree murder, kidnapping, official misconduct and other offenses. As of this writing, two more police officers who were present at the savage beating have been fired, including Preston Hemphill and another unnamed officer. The Memphis Fire Department has also fired three EMT workers who failed to render what may have been life-saving first aid in the aftermath of Nichols’ beating.

Tyre Nichols wasn’t killed because police weren’t trained enough. He was killed because police training in the United States is fundamentally broken at the systemic level. In order to stop police terror, the national conversation now needs to evolve from “more training” to a fundamentally deeper form of accountability.

A systematic lack of accountability feeds police terror

It’s hard to overstate how different the response to Nichols’ killing has been in comparison to other high-profile police killings. While the Memphis officers in question haven’t yet been convicted, the fact that criminal charges were announced so quickly is a stark contrast to other notable police killings of citizens, like the killings of 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio in 2014; Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland in 2015; and Philando Castile in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2016:

-

Before he was killed, Tamir Rice was playing with a toy gun at a public park when police were called. Despite Officer Timothy Loehmann shooting Rice at point-blank range on video within seconds of arriving on site, both the county district attorney and the US Department of Justice (DOJ) declined to prosecute him. Loehmann was eventually fired from the force, but due to an unrelated incident.

-

25-year-old Freddie Gray was snatched off the street by officers with the Baltimore Police Department for allegedly possessing a switchblade. 45 minutes later, he was found unconscious and his spinal cord was nearly severed. Six officers were arrested in connection to Freddie Gray’s death, but not one was convicted. The United States Department of Justice even declined to prosecute any of the officers in federal court.

-

32-year-old Philando Castile – a school cafeteria worker – was with his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, and Reynolds’ 4-year-old daughter when St. Anthony (a Minneapolis suburb) police officer Jeronimo Yanez stopped Castile for a broken taillight. As a gun owner, Castile followed Duty To Inform protocol by telling Yanez he had a firearm in his car, which requires gun owners alert police about firearms in their vehicle when pulled over. Within seconds of Castile telling Yanez about his weapon, Yanez fired five shots into Castile at close range. Reynolds recorded a livestream of Castile’s final moments while Yanez hysterically shouted at her. Yanez was prosecuted, but acquitted by a Minnesota jury.

These high-profile cases are unfortunately reflective of the norm, and demonstrate how difficult it is to prosecute a police officer, let alone find them guilty. It could be argued that the more police are acquitted or not charged after killing someone on video, the more emboldened they’ll feel to do so in future encounters.

Mapping Police Violence tracked more than 9,000 instances of US police killing citizens between 2013 and 2021 and found that of those 9,000 instances, only 104 police officers were actually charged with a crime. And of those 104, only 22 were convicted. That means that over eightnine years, police officers had a 99.76% chance of avoiding conviction on any charges resulting from killing another human being, and a 98.85% chance of avoiding criminal charges altogether.

The way we train police officers feeds police terror

What all of the aforementioned cases have in common is that all of these officers were thoroughly trained. John McLindon, an attorney for then-Baton Rouge, Louisiana police officer Blane Salamoni (who killed Alton Sterling in 2016) correctly said that his client “did exactly what he was trained to do.” Before he killed Philando Castile, Jeronimo Yanez attended a training called “The Bulletproof Warrior,” which conditions officers to believe any routine encounter could be fatal, and that they shouldn’t hesitate to escalate and use force in order to protect themselves.

Katie Sponsler, a former National Park Service ranger who is currently running for the Virginia House of Delegates, described her experience with similar forms of training in three separate police academies. According to her campaign website, Sponsler was rejected from a federal law enforcement academy despite passing all of the graded tests. Sponsler tweeted that this was because she questioned the ethics of her training:

I have been taught to yell “stop resisting” and “drop your weapon” after firing a gun, because bystanders will remember you said it and their memory will automatically reverse the order of the events to make it make sense. Their testimony will support yours, because of this.

I have been told to “loosen up and have fun, it’s fun! Why are you so serious?” When doing a shoot/don’t shoot scenario training.

I have been told that deescalation techniques will get me and other officers killed and as a smaller LEO, I was justified escalating my use of force faster than my colleagues because I was always in danger so I should use it.

I’ve been told my only job is to go home at night.

I’ve been told all of these things in formal, controlled and regulated Police Academies. I have gone through 3. I have heard some of these things more than once.

When I questioned these things in my third academy, and stated that they were inconsistent with the ethics of policing, I was kicked out of the academy on my last day. I had completed and excelled at all the graded tasks, but was told “you aren’t what we want in our force.”

While there is something to be said about providing different kinds of training that emphasize de-escalation, it’s not accurate to say the reason there are so many instances of police killing citizens is due to a lack of training. Rather than simply look at how to re-train police officers, it’s important to zoom out and look at how to restructure the institution of policing so it truly serves the public and ensures accountability.

Choosing the right response to police terror

The rallying cries of the George Floyd uprising of 2020 – “defund the police” and “abolish the police” – went flatly ignored by both city and federal governments in the wake of the protests.

Despite the historic levels of participation in the wave of mass protests that erupted following the killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, ABC News found in 2022 that, of 109 police budgets analyzed, 91 agencies actually saw their funding levels increase. And despite winning election during the year of the uprising, President Joe Biden actually proposed funding for 100,000 new police officers in an August 2022 budget recommendation.

Proponents of the police abolition movement make an excellent case, as Josie Duffy Rice did in her comprehensive essay on the call to abolish policing in Vanity Fair in 2020, but the political will to do so is simply not yet there. What’s needed instead is a list of easily adoptable solutions that would drastically reduce police terror, while increasing police accountability.

One potential solution is having a separate traffic enforcement agency entirely, in which unarmed personnel patrol roadways and ticket drivers for speeding, driving under the influence, and safety equipment in need of repair. Yale Law student TJ Grayson and Yale Law professor James Forman Jr. made this argument, pointing out that in 2015, 11% of all instances of police killings of citizens were during traffic stops, with Black people making up a disproportionate amount of those killings. Police involvement would be limited to more dangerous situations.

Advocates for police reform have called for the passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021, which bans controversial submission methods like chokeholds, and directs the USDOJ to create accreditation criteria for police departments in regard to racial profiling, bias, and duty for officers to intervene when another officer is violating a citizen’s rights. It would also end so-called “qualified immunity” for police officers that kill people, and would establish a national database documenting police misconduct. This would be a huge improvement compared to the current system.

In addition to that legislation, a more radical proposal to pursue at the local level that could result in far fewer fatal shootings of citizens and far greater accountability for police officers is making police brutality settlements come out of police pension funds, rather than from city taxpayers. A 2022 Washington Post investigation found that, of almost 40,000 payments from the nation’s top 25 largest police departments and county sheriff’s offices, local taxpayers have contributed more than $3.2 billion in police brutality settlements over the past decade. By making settlements come from police pension funds instead, police officers would be financially incentivized to not only do their utmost to protect citizens’ civil rights, but to also intervene when their fellow officers are engaging in behavior that could cost them their retirement.

The death of Tyre Nichols doesn’t have to be in vain – there are numerous opportunities for action at the local and national level to rein in out of control police terror. All that’s needed is grassroots action to get it done.