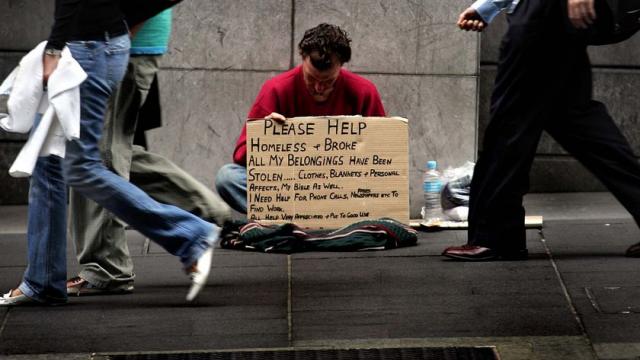

All over the country we are hearing about the poor treatment of homeless people. In New York City, it is actually illegal to donate food to homeless shelters — a policy that came on the heels of actions taken in the 1990s by Major Rudolph Giuliani, who "cleaned up the streets" by essentially sweeping the homeless population under the rug.

Now, these actions are spreading to the south. In the North Carolina capital of Raleigh, it has become illegal to feed the homeless. And South Carolina has even taken things a step further, enacting what amounts to a policy of "exile" for those without homes.

The events leading up to the mass exodus of homeless people from South Carolina started with a series of complaints from business owners in the downtown area of Columbia. The City Council responded with promises that it would do everything in its power to keep homeless citizens out of the downtown area.

That promise was most notably kept by Councilman Cameron Runyan, who called an emergency meeting now known as the “Emergency Homeless Response Plan.” The plan — which was voted on in a 3:30am early morning session and did not receive unanimous approval — allows for police officers to remove homeless people from downtown Columbia and put them on a shuttle transport to take them to a shelter on the outer edge of the city.

If someone resists or refuses to be taken away, s/he is subject to arrest. Susan Dunn, the legal director of South Carolina’s ALCU chapter, said, "The underlying design is that they want the homeless not to be visible in downtown Columbia. You can shuttle them somewhere or you can go to jail. That's, in fact, an abuse of power."

The ACLU sent an inquiry about the plan to the City Council. Victoria Middleton, who directs the organization in Charleston, said the organization has grave concerns about what the bill will mean, and question how so many members of the council voted for a bill they did not fully understand. Some thought the plan would lead to a winter shelter for homeless people opening in Columbia sometime earlier this year.

Now, “the city is denying that it is criminalizing the homeless,” said Middleton, but “you just can’t arrest people because their status is homeless.”

The new “quality of life" law, as some officials call it, is also being seen from a very different prospective through the eyes of the National Coalition for the Homeless.

"[This is the] most comprehensive anti-homeless measure that I have ever seen proposed in any city in the last 30 years," said Michael Stoops who directs the NCH in Columbia. “Using one massive shelter on the outskirts to house all a city’s homeless is something that has never worked anywhere in the country.”

The ACLU's Victoria Middleton added that there is a problem if faith-based shelters are the only ones available to homeless people on the outskirts of the city. Those shelters have specific rules, and if people with no other option than jail are forced into a faith-based shelter, it represents a violation of their First Amendment right to freedom of religion.

According to Middleton, the ALCU is concerned these shelters will force their inhabitants to essentially go to church in order to get a bed.

Columbia’s City Council was scheduled to meet again this week to clarify what the new law means, whether or not it is illegal, and who will be subject to it in the future. Councilmen Runyan did not respond to questions for this article.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments