“People from my community and I were beaten, detained or jailed unnecessarily for opposing tree felling in our forests, some years ago. We visited the police station multiple times for their release. The government didn’t assist the injured. Despite the police and government indifference, we will fight for our land and environment.” - Nivada Debi of the Tharu Adivasi community, Uttar Pradesh, India

Land rights have been central to the struggles of indigenous peoples across the globe for centuries. Although they collectively claim ownership of more than half the world’s land, aboriginal people “are legally recognized as holding only 10 percent.” In the modern era, large scale agriculture, illegal logging and extractive industries are the greatest threats to what remains of their living environment.

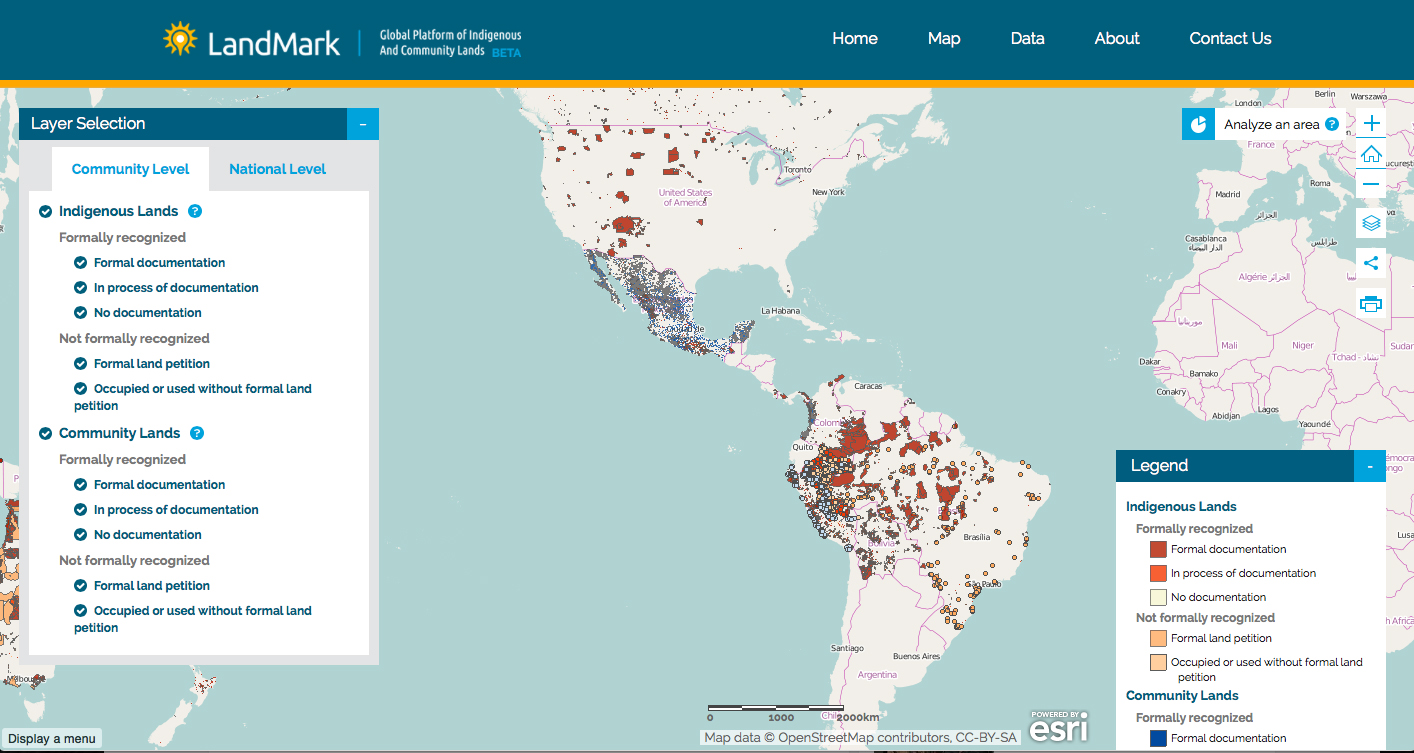

Now, a new website launched by Landmark: Global Platform of Community and Indigenous Lands is using interactive maps to show which groups are claiming land and where, as well as what the land's legal status is. LandmarkMap provides information about indigenous and community lands on two levels: national and local.

On the national level, as the site explains, information is broken down into two main categories: the first shows the percentage of land “held or being used by Indigenous Peoples and Communities," while the second gives a country by country “snapshot of the legal security of indigenous and community lands.”

For example, looking at North America country by country, and narrowing the search to those claims that are formally recognized, we see that in Canada, 43.9% of the country’s land mass is formally recognized as belonging to indigenous people. In the U.S. (including Hawaii), the percentage is 3.7%, and in Mexico it's 55.6%, including community lands.

These numbers need a little explanation. The number of indigenous people in Canada is disputed for a variety of reasons, but is generally agreed to be over 4% of the population. Indigenous people are also the fastest growing demographic in the country. In Mexico, the self-identifying indigenous population is almost 15% of the total population. Both countries contrast sharply with the U.S., where Native Americans only account for around 1% of a population of 320 million.

Another reason for the disparity between the U.S. and its North American neighbors is the issue of community held land, rather than indigenous land. Mexico remains in many respects a subsistence rural society, especially the south of the country where larger numbers of indigenous and mestizo people live. Much of the country's land, especially forest land, is held by communities in common, and the rights of these citizens are generally recognized by the federal government (although recent changes to the country’s energy policy have endangered this). In the U.S. and Canada, community lands in this sense don't really factor into the equation.

However, whether speaking about Canada, the U.S. or Mexico, even formally recognized indigenous lands are still at constant risk of illegal logging or, in many cases, the discovery of natural resources on or beneath them. In Canada especially, where native land claims are usually honored right up until they are not, Landmarkmap could become a valuable tool for activists seeking to preserve the integrity of indigenous communities and their territory.

Importantly, the site also enables viewers to determine the overall legal security of land claims, which are broken down into separate categories for indigenous and community lands. The user can even further narrow the focus using 10 different indicators, including rights to water, trees, and other natural resources.

On the community level, the site shows “the boundaries of lands held or used by indigenous peoples, including lands that are formally recognized by government and those that are held under customary tenure agreements.” It does this using a color-coded system to show the various forms of recognition and non-recognition for both indigenous and community lands on the local level. In the U.S., for example, users can look at individual reservations anywhere in the country and see both the recognized and unrecognized claims of different communities.

The ability to narrow the focus down to the local or community level allows interested parties to see the legal claims on different lands throughout the world. This could be the most vital function of LandmarkMap, serving the people who live in places where states are moving in on traditional lands deemed not to be in “use” – and where the indigenous people themselves might not even be aware of the legal boundaries of their own territories.

Thirteen groups from around the world developed Landmarkmap – from Liz Alden Wiley, a land tenure specialist in Kenya, to NGOs working in Indonesia, the UK and the U.S., including the Washington, DC-based World Resources Institute. The tool's creators acknowledge it is still a work in progress, and are actively encouraging users and interested parties to supply further data.

Updates based on this information will be made to the site, turning LandmarkMap into what could be the most authoritative source for indigenous people and communities seeking to secure rights to their most vital resource: land.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments