decade before United Nations climate scientists issued a “code red for humanity,” the 20-year-old college junior Evan Weber joined several thousand protesters descending on Wall Street to declare a code red for democracy. At the height of the Great Recession, Weber and his generation saw the climate crisis staring them in the face, along with exploding wealth and income inequality, student debt, and housing and health-care costs. On September 17, 2011, they rebelled. Pointing a finger at banks, corporations, and the wealthiest 1 percent, whom they blamed for corrupting our democracy by buying elections to control the legislative process, the protesters camping in Zuccotti Park issued a clarion call for justice: “We are the 99 percent.” That fall, hundreds of thousands of people joined Occupy Wall Street and its partner occupations in more than 600 U.S. towns and cities. Overnight, the movement created a new narrative around economic inequality—and seized the public’s attention. Polls showed that a wide majority of Americans supported Occupy.

Then, almost as quickly as it had arrived, the movement appeared to vanish, leaving behind little except for the language of the 99 and the 1 percent. In the decade since, the wealth gap has only widened. The rules haven’t changed; our system remains rigged to benefit those at the top. And yet, on the tenth anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, it’s clear that the movement has had lasting, visible impacts on our political and cultural landscape—igniting an era of resistance that has redefined economic rights, progressive politics, and activism for a generation.

Reinventing Activism

At its core, Occupy made protesting cool again—it brought the action back into activism—as it emboldened a generation to take to the streets and demand systemic reforms: racial justice, women’s equality, gun safety, the defense of democracy. As the Occupy veteran Nicole Carty told me, “We can’t unlearn the 99 percent. Now what you have is a whole generation that is growing up in movement times, which explains all the escalation you’re seeing and the work that’s happening among very young people who were still kids during Occupy.”

Rewriting the protest playbook, Occupy introduced a decentralized form of movement organizing that enabled hundreds of city chapters to reinforce and strengthen one another yet remain independent—a sharp break from the traditional, hierarchical structure of protest movements of the past. Pioneering the use of live-stream technology while employing powerful social-media messaging and meme tactics to grow participation both on- and offline, Occupy showed a new generation how to turn social movements into a viral spectacle that seizes control of the public narrative.

More deeply, the movement on Wall Street injected activists with a new sense of courage: Confronting power and issuing demands through civil disobedience is now an ingrained part of our political culture. In the years since, a cascade of social movements influenced by Occupy have altered the national conversation, including Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, the Women’s March, Indivisible, and March for Our Lives. On a fundamental level, “we changed the way that people hear and see and understand and process a narrative of resistance,” the former Occupy activist Dana Balicki said.

And in a sense, the protesters have never gone home. Harry Waisbren, who helped lead the movement’s online efforts at Zuccotti Park, told me, “The individuals and the networks would go on and start new projects, and you’d keep seeing them over and over at the cutting edge: The same people who were in Occupy Wall Street were in Black Lives Matter, the People’s Climate March, the Sunrise Movement. Some of the top activists of this generation got their start at Occupy.”

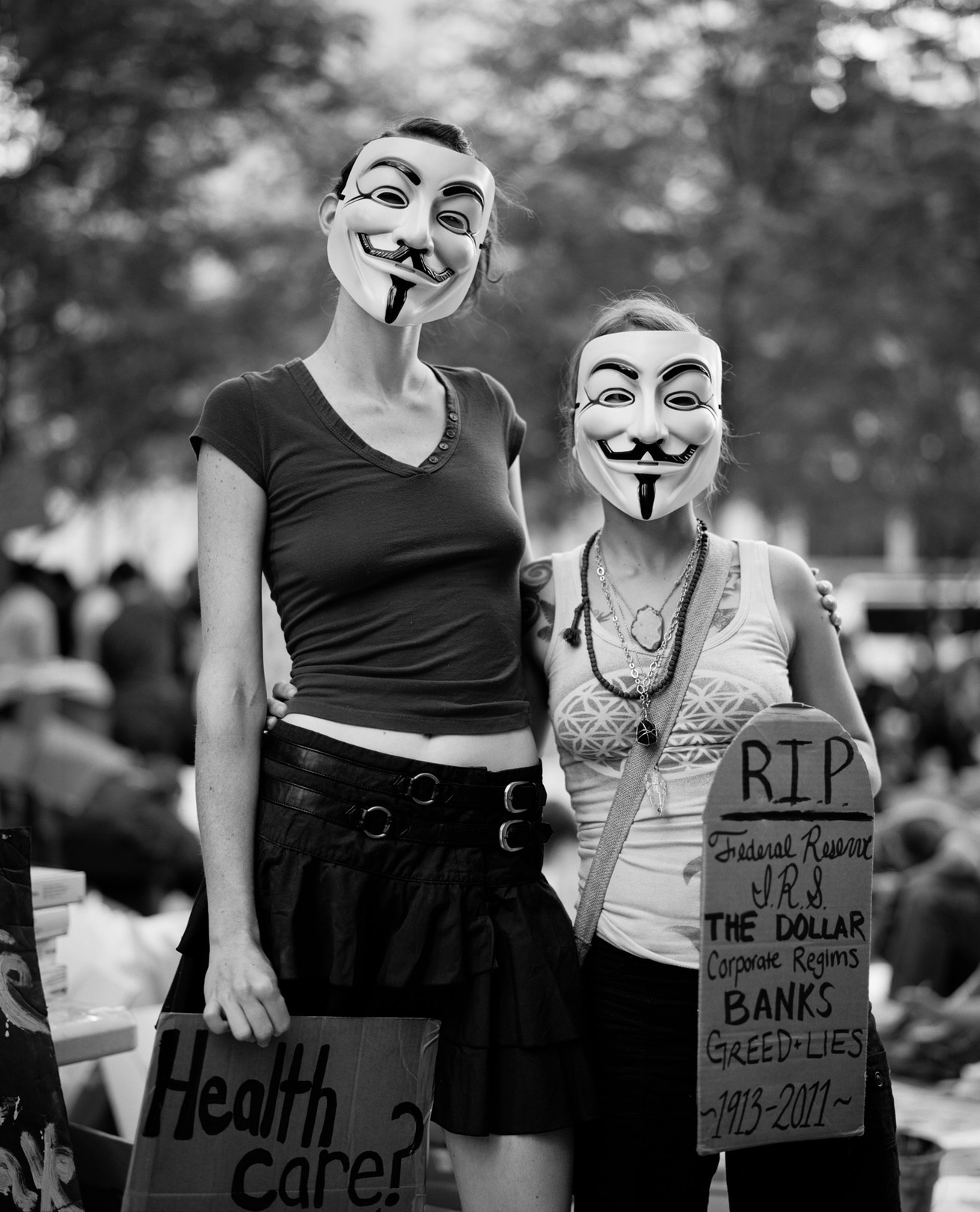

Protesters in Zuccotti Park, New York (Brian Shumway / Redux)

From Occupy to the Green New Deal

The Sunrise Movement, the youth-led climate organization that Weber co-founded in 2017, is today among the loudest voices—in the streets and at the ballot box—demanding transformative, Green New Deal–style policies in Congress’s $3.5 trillion budget bill. The impassioned Gen Z climate generation didn’t come out of nowhere. It emerged as a direct successor to Occupy, whose activists helped redirect the fight against inequality into a focused, strategic movement to save the planet.

The six-year battle that defeated the Keystone XL pipeline and the 10-month defense of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe in its challenge against the now-illegal Dakota Access Pipeline are two other examples of Occupy galvanizing the U.S. environmental movement as activists recommitted themselves to halting oil, gas, and coal infrastructure projects nationwide. From the fossil-fuel-divestment campaign to the 2014 People’s Climate March, which preceded the Paris Accord, and from Extinction Rebellion’s militant direct actions to the global climate strikes that brought millions of young people into the streets in 2019, Occupy’s groundbreaking message and tactics set the modern climate movement on its course.

Some of the most skilled Zuccotti Park organizers also later founded the organization Momentum to train activists such as Weber to develop tangible policy goals and create a road map for enacting long-term, structural change. As a result, Sunrise helped marshal the youth vote in the 2018 midterms to elect a slate of House progressives including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who would elevate the group’s climate-jobs plan—which came to be known as the Green New Deal—to the top of the Democratic Party platform.

The Wage Rebellion

In dollars-and-cents terms, Occupy changed the way Americans understood their role in the economy, inaugurating a decade of labor unrest as employees became activists and workers rediscovered their power. In the fall of 2012, a year after protesters were evicted from Zuccotti Park, Occupy organizers working in coalition with unions and nonprofits took the message of economic justice to those most ready to hear it: low-wage earners seeking a $15 minimum wage. When the first several hundred fast-food workers in New York City walked off their jobs demanding higher pay, better working conditions, and the right to form a union, that marked a breakthrough for organized labor, opening a new workers’ front known as the Fight for $15.

In response, voters and legislators raised the base pay in more than half of U.S. states; dozens of cities, including Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C., established a $15 minimum. Democrats nearly managedto include a $15 federal minimum wage in the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, which President Joe Biden signed into law in March, revealing how much the economic demands spurred by Occupy have reshaped the national discussion.

The fight against income inequality transformed the labor movement in other ways, as Occupy activists in 2012 began helping organize nationwide Black Friday strikes at Walmart, which eventually led to higher pay for half a million employees at the world’s largest retailer. The uprising spread across the low-wage sector—encompassing striking janitors, airport staff, nurses, domestic workers, hotel workers, hospital employees, construction workers, supermarket clerks, and others—shifting the balance of power between employers and employees. The decade-long wave of worker protests achieved its greatest visibility and impact in 2018, when public-school teachers launched strikes to demand raises—which they won—across a dozen states, including West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona, and the Carolinas, in what became known as the Red State Revolt.

The steady uptick in labor activism seems to be moving the needle. In March, the House passed the most pro-union bill in decades—the Protecting the Right to Organize Act—to strengthen labor protections, expand collective-bargaining rights, penalize employers who violate labor laws, and weaken right-to-work laws. Forty years after Ronald Reagan crushed the air-traffic controllers’ strike, dealing a generational blow to America’s unions, the nation appears to be entering a new, more robust era of worker demands—accelerated by conditions in the coronavirus economy, and again, reflecting the distance the country has traveled since Occupy issued its seminal wake-up call to the 99 percent.

Occupy Wall Street protesters in November 2011 (Marcus Yam / The New York Times / Redux)Remaking the Democratic Party

But perhaps Occupy Wall Street’s most seismic and discernible impact has been on politics itself—shifting the window of what is deemed politically acceptable discourse and pulling the nation to the left. Prior to Occupy, no mainstream legislator in Washington dared to criticize capitalism’s thorough corruption of our politics: the obscene wealth gap, the laws designed by corporations, the billionaires evading taxes, and the revolving door that keeps the 1 percent in charge. That all changed with Occupy, which declared that economic injustice and inequality were deliberate outcomes of policies shaped by Wall Street’s greed. By framing the populist economic message that thrust anti-corporate lawmakers such as Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Ocasio-Cortez into the electoral spotlight, Occupy Wall Street arguably did more in six months to move American politics to the left than the Democratic Party was able to do in six decades. Which raises the question: Could Sanders and his political revolution have been possible before Occupy shattered decades of silence about income inequality? Not likely.

As Representative Ro Khanna from California’s Seventeenth District, which includes Silicon Valley, told me, “Sanders’s and Warren’s life’s work was happening well before the Occupy movement, but I’m not sure the country would have been ready to listen to their voices—and I don’t think they would have emerged as national figures—if it weren’t for Occupy putting the issues of wealth and income inequality front and center.” Some imagined that the movement would transform into a political force: a Tea Party of the left. Although the transition never happened, Occupy achieved something perhaps even greater. According to Khanna, it “created the conditions for the emergence of a progressive wing of the Democratic Party, and in the long run, the progressive wing is ascendant and is likely to succeed.”

The movement was particularly instrumental in the rise of Sanders, whom many would later call “the Occupy candidate.” When Sanders first got on the national map in 2015’s primary season, it was thanks in large part to a group of Occupy activists who had repurposed their digital-organizing and social-media talents into a viral movement called People for Bernie. Operating independently of the Sanders campaign, the group created a horizontal model for voter engagement by inviting volunteers across all regions and demographics to help the Sanders phenomenon spread in the distributed, decentralized format of a social movement.

“We understood how to mobilize the internet,” Charles Lenchner, a co-founder of People for Bernie, said. “We trusted the people and told them to do what they thought was right. We gave away the keys.” The tactic drew millions of supporters as it empowered people to become stakeholders propelling the movement. The group fueled Sanders’s meteoric ascent, particularly among Millennials, as the campaign introduced small-dollar fundraising as a winning strategy and activated a new generation’s engagement in the democratic process.

By reinventing digital electoral politics, Occupy veterans helped put a once-fringe Democratic socialist into the leadership of the Democratic Party, where he was able to move progressive priorities—Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, debt-free college, a $15 wage, higher taxes on the wealthy—from the periphery into the mainstream. Sanders would provide the springboard for Ocasio-Cortez and a generation of anti-corporate lawmakers to begin to remake one of America’s two major parties, as social movements shaped electoral outcomes. In the words of Maurice Mitchell, the national director of the Working Families Party, “Occupy shifted the political culture of the U.S.,” birthing an era in which “liberals have been radicalized, and radicals have been electoralized.”

When I interviewed Evan Weber for my book about Occupy and its legacy, he agreed that the movement played an essential role in igniting a new progressive era—one that might finally be on the verge of achieving transformational social, economic, and electoral reforms. “AOC wouldn’t have run if Bernie’s campaign wasn’t as successful as it was, and Bernie’s campaign wouldn’t have resonated and been successful if not for Occupy,” he said. “Occupy helped create a mood and understanding in the country of the populist moment that we’re in, where so few have so much at the expense of the rest of us.”

Occupy was like a great wave hitting shore—and a warning of even bigger waves to come. Among the slogans and chants that resonated at Zuccotti Park, one in particular has echoed through the decade: “This is what democracy looks like.” For a generation whose time to solve the climate crisis is running out, government must now deliver. The alternative, Weber warned, may drive “an army of young people to begin flexing its muscles” on a scale not seen since the 1930s, through disruptive resistance featuring “mass sustained shutdowns, occupations, and general strikes.” As the turbulence of the past decade has shown, systemic crises must be confronted. Occupy provided a blueprint for how popular dissent and demands can change America. Now a new 99 percent must write the next chapter.

This article was adapted from Michael Levitin’s book Generation Occupy: Reawakening American Democracy.