The well-manicured lawns and glistening gardens at Pueblo Serena Mobile Home Park in Sonoma look green and lush, not surprisingly because they’re well watered. The residents, many of them retirees, and more than a few of them avid golfers, don’t seem to know that there’s a drought in this town and all across California. Or perhaps they know and don’t care. The swimming pool is full, too, with clear, clean water — a luxury on hot summer days when it’s 90 in the sun.

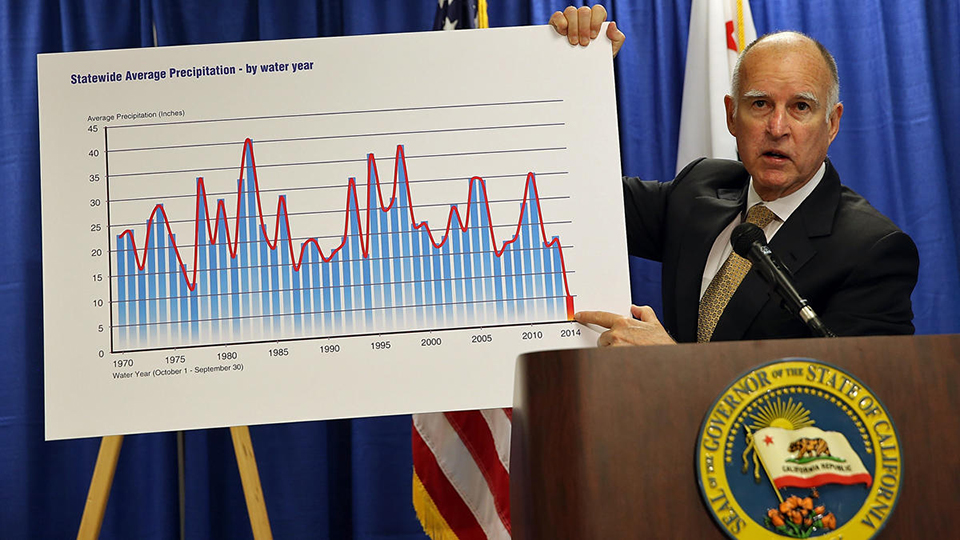

Five months after California Governor Jerry Brown announced a State of Emergency in response to the drought, Pueblo Serena Mobile Home Park looks as green and lush as it does most summers. Moreover, the residents aren’t behaving as though there’s an official state of emergency.

Still, there are conscientious residents who conserve water by taking shorter showers and flushing toilets infrequently. They’ve also ripped out their beloved green lawns, put in rock gardens and switched to drought-resistant native plants. The conservationists among them, including community activist Lin Marie deVincent, find it difficult if not impossible to persuade their seemingly unconcerned and intransigent neighbors to turn off sprinkler systems that run for hours. In a state of emergency in which conservation is voluntary, citizens of the Golden State write their own individual water plans and adhere to their own rules. There are no water cops to bust them, at least not yet.

Grape growers and vineyard owners in the counties of Sonoma and Napa — at the heart of Northern California’s wine region — don’t seem to care much about conserving water, either. Grape growers explain that they’re paid by the ton; the more they irrigate, the bigger and the heavier the crop at harvest and the more money they make. There was less rain this year than in recorded history, but grape growers are irrigating more than they have in the past.

It all seems rather perverse to environmentalists such as Sonoma County’s Jane Nielson, a geologist with a PhD who told me that “hydrologists are making dirty money by giving false information.” Then, there’s Professor Michael Klare, an expert on resources such as coal, gas – and now water – who told me that California was in for “fierce winter storms along the Pacific and severe droughts inland,” all of which would create deeper social and economic crises.

Northern Californian environmentalists who monitor water and wine, such as Jane Nielson, say that it takes 1,000 gallons of water to make one gallon of wine. That includes water in the winery as well as water in the vineyard. Oak barrels have to be washed out; cement floors washed down. Then, too, when new vineyards are planted — and they’re planted all the time — drains are installed in the fields to take water away rather than sink it in the soil. Water for grapes is then pumped out of the ground, which lowers the water table for everyone. How much water is pumped out no one really knows; it's hush-hush, and there are no statewide regulations for ground water extraction.

A Case Study in Dry Farming

Tall, bearded Will Bucklin dry farms most of his vines at Old Hill Ranch in the gentle rolling hills outside the town of Glen Ellen in Sonoma County. Founded in 1850, the same year that California became a state, Old Hill is one of the oldest vineyards in California. The ancient vines certainly look gnarly. They’re also spaced out, not jammed together, a common pattern at other vineyards in the majestic Valley of the Moon, where novelist (and Socialist) Jack London lived and wrote from 1905 until his death in 1916, and where he made non-alcoholic grape juice and plastered his own picture on the label of every bottle. London was involved in the water wars of his own day. When he damned up a stream his neighbors took him to court. He won, probably because he was Jack London, the celebrity author.

Will Bucklin lives in the shadow of London’s thousand-acre-plus Beauty Ranch. He also lives much more modestly than London in a small house adjacent to his vineyard. In these parts, he’s unusual in that he’s a resident grape grower and wine maker. He doesn’t have a vineyard manager. Indeed, he walks his fields every day with his dog, Tanner, and knows his vineyard as well as he knows the proverbial back of his own hand.

Bucklin insists that grapes that are not irrigated make for better wine than grapes that are irrigated. His wine certainly suggests that he’s doing something, if not everything, right. (After college, Bucklin worked in the wine industry in France, where dry farming is de rigueur, and where he learned much of what he knows about grapes and wine.) Bucklin makes excellent Zinfandel; it might be the best in the Golden State, perhaps because his vines have to struggle to survive in the heat while the roots have to struggle to find water in the dry soil. Or maybe it’s because he brings them along as though they’re his children with a kind of tough love.

“The other grape growers around here think I’m crazy because I dry farm,” Bucklin tells me on an afternoon when the late-afternoon sun beats down on our heads. “I think they’re crazy, especially now in the midst of this drought when they’re irrigating like there’s no tomorrow.” He adds, perhaps a tad sarcastically, “It’s fine with me if people don't worry about water. I’m sure they’re happier souls. But if they’re not worried about it because they think that the problem is going away, then I have no problem telling them they’re idiots. They can choose not to worry, but don't tell me there’s no problem.”

Bucklin’s mother, Ann Teller, owns and operates a forty-acre organic farm adjacent to the vineyard in the Valley of the Moon. An environmentalist and, in many ways, the matriarch not only of her family but of the larger community in which she lives, Teller has long had a heightened awareness about water as a valuable resource. She’s also committed to sustainable agriculture, food safety and fair employment. Her former (second) husband, Otto Teller, also a staunch environmentalist, became irate when he saw three disturbing patterns develop in his own lifetime: new houses rising up all over the Valley; vineyards marching up and down the hillsides; and no one paying attention to diminished water resources.

Much the same patterns have played out all over Sonoma and Napa counties in the past four decades. At the top of the food chain, there’s the grape and wine aristocracy that as a group doesn’t care about the environment or Mexican farm workers, the California equivalent of the peasantry.

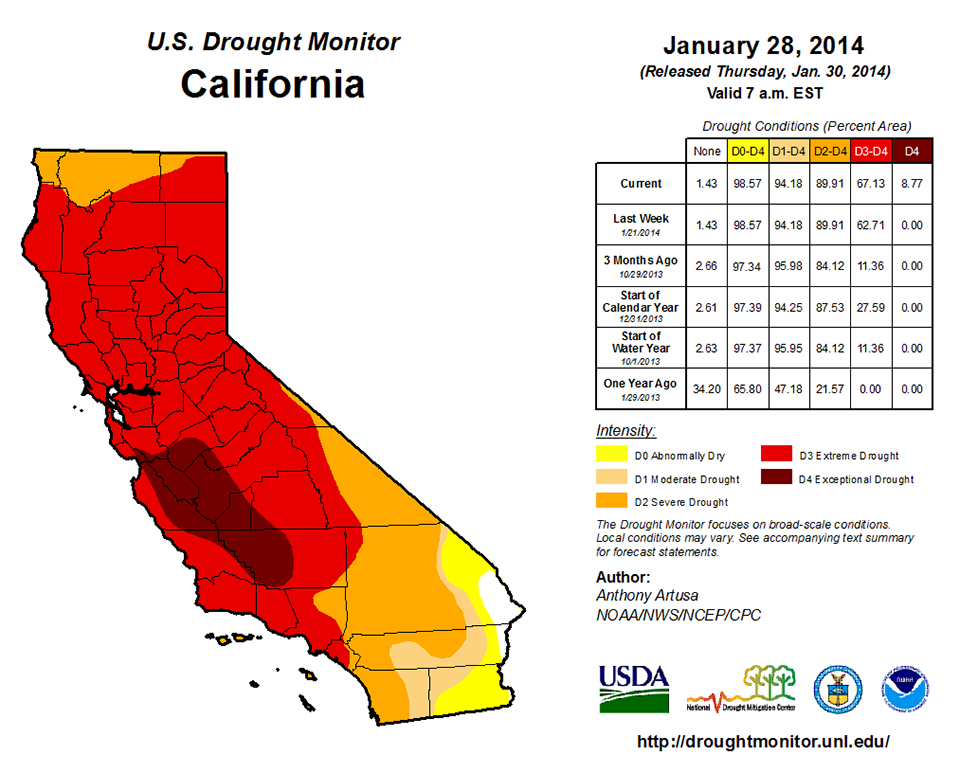

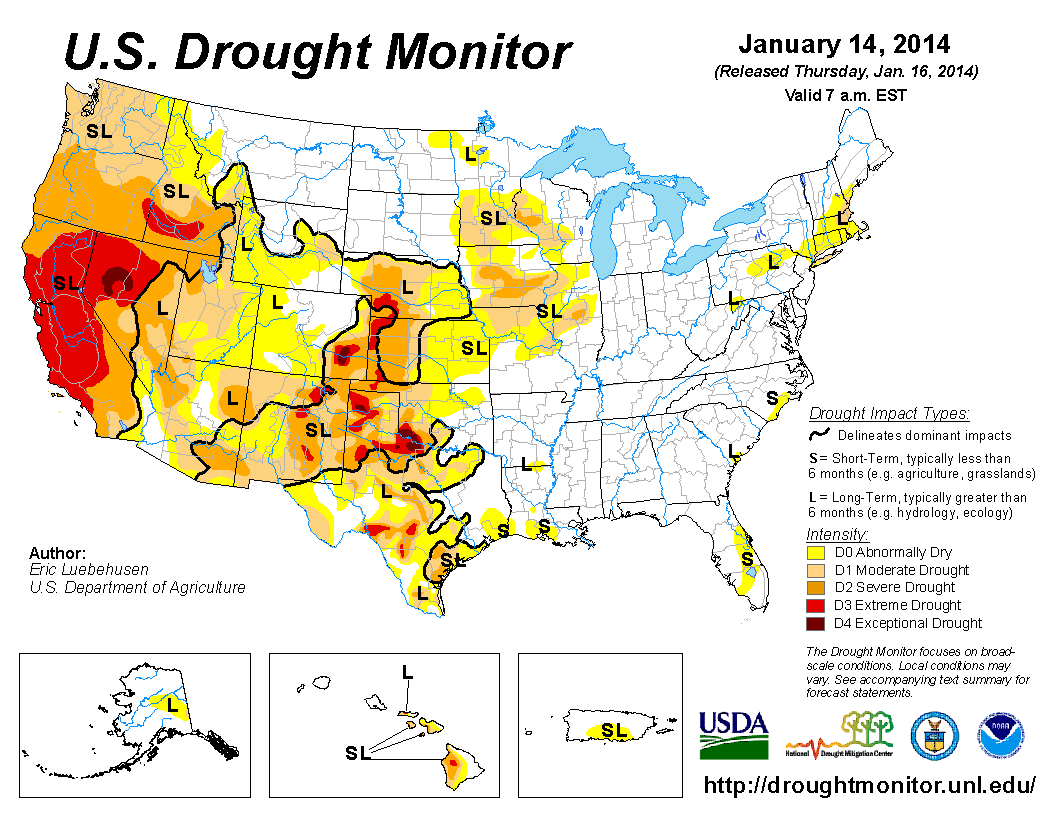

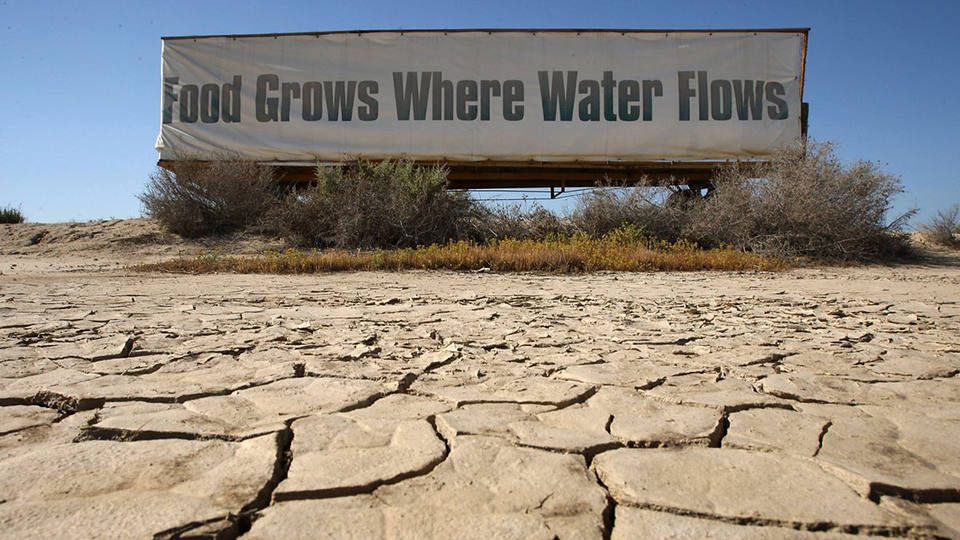

Otto Teller remembered a time when streams ran year round and when fish swam upstream to spawn. These days, most streams only have water in the rainy season, which, this year, was greatly abbreviated. This June, there isn’t a stream around with a drop of water. Sonoma Creek is running almost on empty and the Russian River, the only major waterway hereabouts, has shrunk to a pathetic trickle. Then, too, Lake Sonoma, a machine-made reservoir, is about 15 feet below normal. On the day I visited, dead fish floated on the lake’s surface and no one knew why, not even weeks later.

Given the new volatile, extreme weather patterns, Ann Teller has made radical changes at Oak Hill Farm. She has all but eliminated corn as a crop not only because it uses a lot of water, but also because it takes up a lot of space and needs a lot of care. Giving up corn was like giving up a guilty pleasure. “I like corn as much as anyone else,” Teller explained in her kitchen on a Friday night. “I like the way it looks. It epitomizes summer, tastes good and fills you up. Corn is sexy, no doubt about it, but it does not provide top value as a nutritious crop and so we have cut way back on the cultivation of corn.”

At Oak Hill, where flowers are as prized as heirloom tomatoes, Teller and Jesus Soto, a natural-born horticulturist, have given up on flowers such as hydrangeas that gobble up huge amounts of water. They’ve also cut down on irrigation of sunflowers, zinnias, snapdragons and cosmos. Moreover, the field workers monitor irrigation more precisely than ever before. Every single crop is on a timer. Crops get no more water than they absolutely need, and yet Oak Hill still waters crops around the clock. Without water the crops would die; without crops the farm would perish.

“We pump all day and all night,” Teller told me. “Water is coming out of the ground all the time some place on the farm, but we have more efficient use of water, and so we’re using less water now than we have in the past.” How much water the farm uses and how much water there is under the ground she doesn’t want to say. No farmer wants to broadcast his or her water resources and for much the same reasons that Ann Teller gives. “I don’t want anyone to know how much water is underground here,” she says. “It might have to go for the public good.” Ground water is California’s dirty little secret.

Few environmentalists in Sonoma have thought as long or as hard about the difficult issues and decisions facing farmers and agriculturalists, as Teller has. In the kitchen while she’s preparing dinner, she says, “The wine industry is more environmentally friendly than houses, roads and people, but it’s not really environmentally friendly.”

She adds, “Still, I’d rather see a vineyard than houses. The Sonoma County supervisors are all about growth. Then, they doll it up with conservation. The whole system is unfair. Government gets involved in the unfairness. I don’t have much faith in us as a species. The natural world is being gobbled up. There are more people now than ever before living longer lives. The human species will be all over everything.”

Teller conserves inside as well as outside her house. Now, when she plans a meal she thinks about how much water she’ll need to wash and clean up as well as cook. “I want to use the minimal amount that’s necessary,” she says. “Water is so valuable. It’s the essence of life, but we haven’t ever really come to that awareness and understanding.”

Committed to Random Acts of Conservation

Benny Soto, a Mexican field worker at Oak Hill and Jesus’s tattooed son, does his part, too, to conserve water whether anyone knows it or not. He doesn’t show off or try to look good for Teller, his father or anyone else. Benny Soto conserves because he wants to conserve, for himself and his own conscience. Perhaps because he’s a half-century or so younger than Ann Teller, he has more faith in humanity and in his own generation, though he also expresses a certain sense of resignation.

On a Friday morning, he looked up at the dry hillsides and shook his head. “The green has already up and gone,” he said. He adds, “The drought is what it is. I take shorter showers even when I’ve been working in the field long hours and come home hot, dirty and sweaty. I turn off the water when I brush my teeth. Maybe someone will see what I’m doing and be inspired to do something similar. I think of what I’m doing as akin to random act of kindness. I’m engaged in random acts of conservation.”

In Sonoma, organic farmers and farm workers understand the need to conserve water better than grape growers, wine makers and the retirees at Pueblo Serena Mobile Home Park who are addicted to their lawns. The organic farmers and farm workers mean to take a stand even if no one sees the stand they take. In the State of California in which there’s no coherent plan to deal with the drought — that would smack of socialism — random as well as coordinated acts of community conservation may be the best that one can expect.

Governor Brown can go on calling for wise use of water. Northern California Congressmen such as Mike Thompson and Jared Huffman, both Democrats, can continue to praise the newly adopted Water Resources Development Act. They can smile and look forward to the end of the Drought. In June, Thompson and Huffman appeared at a photo-op in Santa Rosa to say they were all for conservation and preservation of endangered species. “Water good. Fish good,” Thompson told the crowd. He made a complex problem seem awfully simple.

Huffman insisted that Northern California needed more accurate data and better predictions about the weather so that water wouldn’t be released (and wasted) from reservoirs, as has been done in the past. “It’s a team effort,” Huffman told the crowd. Indeed it is, though perhaps not as he envisions it. If California does beat the drought this summer it will probably be in large measure because of the efforts of young, hopeful farm workers like Jesus and Benny Soto and wise old farm owners like Ann Teller, though a great many stories about the drought leave out both the farmers and the farm workers. There weren’t any farm workers or farm owners at the Santa Rosa press conference.

All wars are fought on the ground, not in the offices of governors and congressman. California’s water wars aren’t any different.

“The water wars have only just begun,” Teller told me on a night when she prepared supper using just one dish. “We all need to conserve water. If our neighbors don’t conserve it, let them live with their own bad conscience.”

Perhaps the specter of the drought will haunt those who waste water, horde it. treat it like a commodity, and don’t see that it’s a sacred element of the Earth itself.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments