“From the Ground Up” is an ongoing series of articles co-conceived by Occupy.com and Commonomics USA, in which we explore people and organizations dedicated to direct action and grassroots projects for economic justice. This is the first of a two-part series previewing the upcoming prison actions happening September 9.

Prisoners Are Slaves

Here’s why the September 9 actions inside and outside of American prisons, undertaken to protest the legalized slavery, dehumanization, and policy failure of correctional incarceration, may be the most important protests of 2016: Prisoners are legal slaves, and as such, whatever is happening to the non-incarcerated in this brutal system is happening worse to the incarcerated.

Beyond the 13th Amendment’s approval of prison slavery, there is a mountain of administrative and judicial rulings permitting prisons to suppress any and all organizing activity. Private prisons go a step further, enslaving prisoners as laborers in their own profit-making ventures.

Our direct or indirect relationship to that labor makes us all party to mass alienation. “On average, prisoners work 8 hours a day, but they have no union representation and make between .23 and $1.15 per hour, over 6 times less than federal minimum wage,” writesKelley Davidson of US Uncut. Corporations such as Wal-Mart, Whole Foods and McDonalds purchase products made by inmates earning pennies per hour – in the case of Whole Foods, prisoners allegedly make 74 cents a day, raising tilapia the company sells for $11.99 per pound.

“We are so alienated from whether the products we consume are produced by slave labor – whether prison slavery here or sweatshops abroad," Azzurra Crispino, a member of the Incarcerted Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC) and co-founder of Prison Abolition Prisoner Solidarity (PAPS), tells me. “We are alienated from each other.”

This terrible interpretation of the constitution won’t be challenged, its legal and commercial underpinnings dismantled, he says, unless people on the inside and the outside create a crisis by striking and demonstrating. The question is how to make people care – particularly mainstream labor organizations with neither the resource bandwidth nor the ideological clarity to include incarcerated workers.

Azzura says she found it easier than some might think to make people care. “I am also the community engagement chair for my local of the American Federation of Teachers. Many teachers are becoming more aware of the school to prison pipeline and want to support prisoners. To me, the key to winning people over to the cause is to humanize individual prisoners,” she says.

“PAPS likes to reconstruct a solitary confinement space on the street and ask passersby to write to prisoners,” says Azzura of her organization, whose tactics include creative, performative protest. “It's heartbreaking to watch people who have been held in solitary sit and stare at the masking tape marking out the space. It’s easy to discount ‘prisoners,’ but showing the individual stories makes that harder.”

Smashing the Corporate State on September 9

There have been several successful protests in prisons around the country in recent years, in states including Georgia, Illinois, Virginia, North Carolina, Washington, California and Texas. Incarcerated activists and their allies have taken advantage of social media and also communicated with one another via unauthorized cell phones and word of mouth. A new hunger strike action by Wisconsin prisoners against solitary confinement began just a month ago.

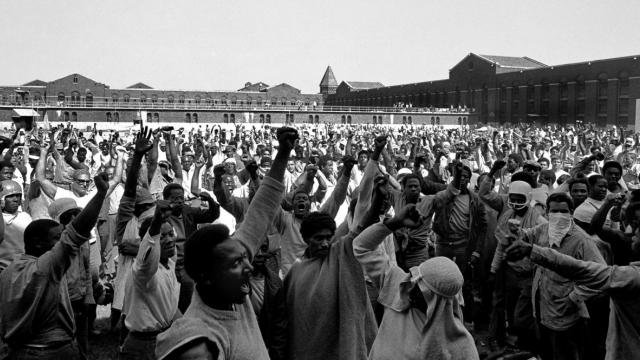

The protests slated for Sept. 9 aim to be a culmination of, and a revolutionary step forward, from previous actions. In April, a prisoner resistance blog published a joint statement by several inmate groups declaring that a nationally coordinated prisoner work stoppage would occur Sept. 9 – the 45th anniversary of the Attica uprising of 1971, considered perhaps the most significant uprising of the prisoner rights movement. The statement concluded: “We prisoners across the United States vow to finally end slavery in 2016.”

But it’s a dangerous chasm for people on the organizing side. Past successes increase the likelihood that guards will brutally suppress the actions of Sept. 9. Organizers have chosen to take that risk head-on – to publicize it and the action itself. This places a huge responsibility on the shoulders of the outside organizers and supporters, and makes it vital that individuals and groups stand up and be part of the action in whatever way they can. “When we stand up to these authorities,” the inmate organizers write in their April statement, “they come down on us, and the only protection we have is solidarity from the outside.”

The struggle doesn’t end with prison labor. Prisons also serve a generally repressive function, of which labor is a particular manifestation. “Slavery, and prison-slavery, is transparently exploitation,” says Jimi Del Duca, Media Co-Chair of the Industrial Workers of the World’s IWOC. “Our goal is to help the public understand that being sentenced to slavery is not helping anyone except the ruling class. It harms the working class and hardens those incarcerated, thus providing future slaves.” With the acceleration of capitalism’s crises and contradictions, Del Duca says, “people listen with understanding today to what they could not comprehend a decade ago.”

Incidental to the revolutionary goals of the Sept. 9 actions, organizations like the IWW, the National Lawyer’s Guild and my organization, Commonomics USA, also hope the actions will inspire dramatic policy changes in our incarceration system, from living wages paid to prisoners to a rejection of incarceration as a default correctional tool.

Del Duca, who has worked in the mental health profession, tells me what many doctors, social workers and legal professionals I’ve talked to also believe: Incarceration is a policy failure. “Offenders should be released the day they are determined to no longer be a threat to the public,” he says. “Those who remain dangerous should be housed in very humane psychiatric facilities, not torture chambers. Limiting incarceration to truly dangerous and violent people is our IWOC goal, and even then with full rehabilitation programs and humane conditions, including therapy and psychiatric treatment as well as real education and skills training.”

“Any of us could end up in prison”

Ending up in prison is also a class issue. “Occupy opened a lot of eyes for people whose class privilege kept them from having negative experiences with police and needless incarceration,” Azzura says. “Black Lives Matter has driven that awareness even further.” There are potentially millions of innocent people in prison and only a few, like Michael Morton (who was wrongfully convicted of murdering his wife after prosecutorial misconduct) are fortunate enough to be exonerated.

“As the Michael Morton story – and so many others – have shown, any of us could end up in prison, even if we do nothing illegal. We owe it to our society and community to begin a new chapter in history,” adds Azzura adds. With enough public support for the unspeakable bravery of organizers and protesters behind bars, Sept. 9 could be a foundation and a spark. What was that thing about nothing to lose but our chains?

Matt Stannard is policy director for Commonomics USA and on the board of directors of the Public Banking Institute.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Matt Stannard replied on

An Apology to Azzurra and to our readers

On Monday, Occupy.com ran an article I wrote about prison uprisings that featured an interview with activist and teacher Azzurra Crispino. Crispino is a powerful, inspiring, female activist. But my hastily-written article calls her "he" twice, and I neither exercised the common sense to make the correct assumptions about her, nor do the minimal research of interview subjects that would have reached this obvious conclusion. The article also misspells her name twice--a result of my poor editing and a hasty posting by Occupy staff. But the fault of all of this is primarily, finally, and irrevocably mine.

That was lazy and sexist of me. I am very sorry, and more than that, very disturbed at what this says about me as a person working in public interest policy and law.

I am currently trying to fix the article itself, and have apologized to Azzurra.

I consider this a really, really serious mistake and wanted to air it publicly so there's no question of my intent to re-think and correct my assumptions and my work practices.

Matt Stannard