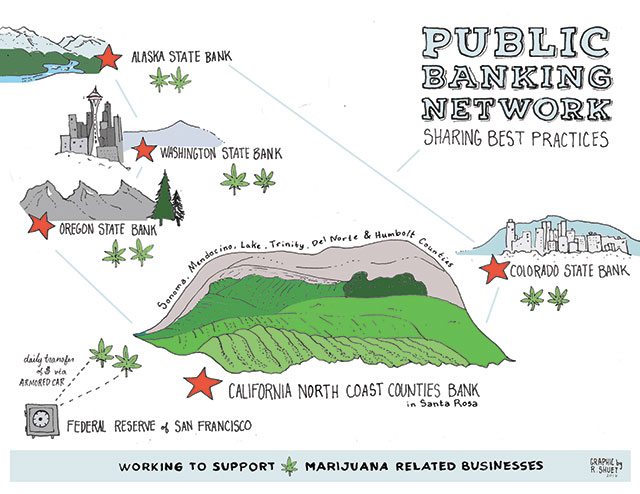

With nearly a dozen state initiatives legalizing recreational marijuana on the November ballot, the market for legalized marijuana is certain to expand. But, because marijuana continues to be classified as a Schedule 1 drug by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), private banks are effectively prohibited from fully participating in this market — the compliance burden is too high and individual employees face the threat of prosecution. A network of city, county and state-owned public banks, sharing best practices, may be an effective way to offload the compliance burden so that marijuana-related businesses can confidently accept payments and deposits can be placed into a network of public banks, which could develop the systems needed for legal compliance with the Department of Justice and federal regulatory agencies. Short of legalization of marijuana, this may be the best way to protect local businesses and banks from a market that is fraught with risk.

The Recreational Marijuana Market

The creation of the recreational marijuana market by the state governments of Washington, Oregon, Alaska and Colorado has directly led to the establishment of a variety of marijuana-related businesses — from growers to retail stores. These businesses are quickly growing revenues and profits. As one of the fastest-growing industries in the United States, national legal sales of all forms of cannabis were $4.6 billion in 2014, $5.7 billion in 2015, and are projected by ArcView Market Research to be $7.1 billion in 2016. If all 50 states and the District of Columbia were to legalize recreational marijuana, GreenWave Advisors projects the total value to top $36 billion.

With licensing and tax revenue in Colorado alone expected to be $135 million in fiscal year 2015-16 (up from $70 million the previous year), elected officials in cash-strapped cities and states recognize the potential budgetary windfall of this market and are eager to bring the industry under their legal purview so they can reap the taxes.

States Promote While Feds Penalize

One would think that, with all that money in the industry, banks would be lining up to provide depository banking and other financial services to marijuana-related businesses. Not so, according to the recent article, "Banking is Not Yet Going to Pot," published in the American Banker. Most banks are ignoring the market and, in doing so, leaving money on the table.

The problem is that, while the states legalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana and provide for the regulation of marijuana production, processing and sale, marijuana remains classified as a Schedule 1 substance under the federal Controlled Substance Act. The classification makes it illegal for any use — which, in turn, makes the revenues it generates an illegal source of investment, akin to old-fashioned "drug money." The DEA's announcement in August 2016 to allow more research into possible medical benefits does not change the illegal status of money generated from this market.

This is a business school case study in the making, where conflicting government positions on marijuana legalization offer a perfect example of an imperfect market. In a market economy, one of the most important roles of government is to define the playing field and to determine the rules so that competing businesses can provide reasonably priced products and services. What has happened with the recreational marijuana market is that state and federal governments have conflicting sets of rules that introduce unnecessary risk into the market for those businesses that choose to participate. Full market participation — and fully realized fee and tax revenues — can only happen if a government entity provides some sort of remedy to the conflicting set of rules.

It's Still a Risky Business

Banks are federally regulated and therefore, more vulnerable to facing federal charges, should they be found inadequately compliant. The federal Bank Secrecy Act requires banks to watch for Anti-Money Laundering (AML) law violations in customers' deposit accounts and requires them to file a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) to FinCEN, an agency of the US Treasury, regarding a customer's suspicious or potentially suspicious activity. Failure to file a SAR can result in criminal and civil penalties, including incarceration for involved employees. Federal law technically says a bank is itself committing money laundering by accepting a deposit of money derived from the sale of marijuana.

The imperfections in the market create risk for both participating financial institutions and marijuana-related businesses. Naturally, credit card issuers and processors shun doing business with pot-related firms. As a result, the marijuana-related businesses, having to resort to a cash-based payment system, end up incurring enormous risk by carrying excessive cash-on-hand. Banks are loath to accept marijuana-related cash as deposits for fear of facing money-laundering charges. The trajectory is to have a sizeable market that is based entirely on cash transactions with mattresses used for safeguarding profits.

Incomplete DOJ Guidance

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) has provided a memo that serves as guidance to banks so that they can accept cash as deposits. But it is not a regulatory handbook, nor does it identify best practices. In other words, it gives guidance for banks on how to evade the law, a solution that is unsettling at best. As a half-remedy, it's the equivalent of the DOJ saying to banks, "You go first and we'll see if it works, and we'll prosecute you if it doesn't." The excessive compliance costs for taking this approach led MBank, a $175 million-asset institution in Portland, Oregon, to shutter its marijuana-related businesses program within a year.

The result is either a lack of banking depository services (forcing marijuana-related businesses into risky cash transactions) or depository services that are provided (at a high price). Some credit unions have jumped into the marijuana market and are charging upwards of $3,500 per month for a deposit account. This kind of pricing is certainly an indicator of an imperfect market.

The Solution: A Network of Public Banks

Of course, the DEA could legalize recreational marijuana and simply end this impasse. Or Congress could pass legislation that protects banks from the risk of handling legitimate money generated by marijuana-related businesses. The risk of participating in this market would be significantly diminished and a rapid expansion of the market to all 50 states and the District of Columbia would likely result. But this is something that neither President Obama, nor the Republican and Democrat presidential nominees, have given any indication of supporting.

Short of the federal government legalizing recreational marijuana, cities, counties or states can resolve the conflict between state and federal regulations by taking on the roles of both banker to the marijuana-related businesses and guarantor to the federal government. In California, a charter city or county can define its own rules for governance through the provisions outlined in its charter. A constitutional amendment in 1879, "home rule" power was obtained by California cities in order to thwart state meddling in municipal affairs. This means that charter cities and counties may provide credit and depository services to their residents, much like they can provide water, electricity, broadband and other utilities.

However, the bank would be more a legal entity than a traditional retail operation. It will have no retail presence, no ATMs, no consumer deposits/loans, and therefore no need for compliance with many requirements of the Dodd Frank Act. A vault is not needed, since any cash would be considered excess and deposited in the Federal Reserve, a standard procedure. As an independent corporate entity (owned by the city, county or state) it will likely consist of bank operations software and just a few cubicles in the treasurer's office. The city financial officer or county treasurer will direct all city/county government deposits generated from taxed marijuana revenue into this public bank. Debt or equity capitalization and governance will need to be addressed — the Bank of North Dakota is a safe and proven public bank that can serve as an effective model.

In order to remedy the imperfect marijuana market, the public bank will also accept marijuana-related deposits. This "excess" cash can be picked up daily and placed in Federal Reserve vaults and credited to marijuana-related business accounts in the public bank. A web interface will allow account holders to transfer this money to their other deposit accounts with private banks or credit unions located in the same state as the public bank. This scenario can be replicated state-by-state with state-owned public banks.

In these scenarios, where a city, county or state public bank accepts marijuana-related business deposits (with the cash physically deposited at the Federal Reserve), the public banking network will need to ensure rigorous compliance with the DOJ's guidance memo on accepting deposits from all the marijuana-related businesses its member public banks serve. Documentation of the origin of the cash will be required to be completed by the marijuana-related businesses before a cash pickup occurs. Enabling smartphone apps that report on specific transactions can help. Other stipulations and practices will be enforced by the public banks so that the rudimentary standards identified by the DOJ guidance memo can be enforced.

One can argue that a network of public banks that solely focus on pot money would do a superior job of setting the gold standard for implementation of the DOJ guidance memo and any subsequent guidance provided by the DOJ or other federal enforcement organizations. In fact, a network of public banks between states that have legalized recreational marijuana can establish best practices in partnership with the primary bank regulatory agencies (the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) and the DOJ. This would be a significant development. If there is a failure in the system, it will be up to these government entities to work it out, with the public banking network protecting business entities from the risk of guessing what the existing DOJ guidance memo or future guidance may mean in terms of actual business practices.

In essence, state, city and county governments will better serve their constituents and create a "level playing field" by leveraging their bargaining power as a consortium of public banks that determine best practices. Agencies from the federal government will need to deal with the entire network/consortium, not individual private banks, providing a more balanced approach to federal law enforcement. And state, county and municipal law, based on community rights, can serve to further buttress the network of public banks.

Bank of North Dakota Sets Precedent

There is a precedent for having a public bank deal with compliance issues in a market economy. In 2011, the North Dakota Bankers Association worked with the state legislature to direct the Bank of North Dakota, the nation's only state-owned bank, into the home mortgage origination business in order to offset the increased compliance burden that community banks were shouldering as a result of the Dodd-Frank legislation. Dodd-Frank was designed to constrain the large Wall Street banks, but inadvertently penalized community banks, and North Dakota has the highest number of community banks per capita in the nation. Rural banks that only saw three to five mortgages a year could not shoulder the compliance burden, leading to business lost to out-of-state banks.

As a result, the Mortgage Origination Program for rural lenders was created by Bank of North Dakota to directly address the twin issues of compliance costs and lost business. The irony of an association of private banks using the public bank — in a red state, no less — as a way to ensure that they could better manage the risk of working in an increasingly federally-regulated market practically leaps off the page. It shows just how responsive a state government can be in meeting the needs of its people. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is a demonstration of how a state government, acting in concert with its own depository bank, can blunt the (oftentimes) heavy hand of federal authority, a situation not all that dissimilar to the one faced by the recreational marijuana market.

The new marijuana market cannot realize its potential if participating banks bear the risk of being federally prosecuted and legitimate businesses bear the risk of using a cash-based payment system as a workaround. Until the federal government legalizes recreational marijuana, a network of public banks working together to implement the DOJ guidance memo can serve as an important way to improve market conditions so that unnecessary risk is not borne by private banks or credit unions, and a measure of safety is provided to cash-based marijuana-related businesses.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments