ATHENS – A small European nation is on the verge of standing up to financiers that are literally strangling its economic surplus and imposing draconian cuts in the same of austerity, as standards of living have plummeted in the past five years.

Greeks are on the verge of electing the leftist Syriza party on Sunday’s general election with at least four polls predicting a 4-point or greater lead over the incumbent center-right New Democracy party, whose privatizations and steep cuts have done little to stem the hemorrhaging of Greek’s monetary wealth to creditors.

“Austerity has failed in Greece. It crippled the economy and left a large part of the workforce unemployed,” Syriza’s 40-year-old leader Alexis Tsipras wrote Jan. 20 in the Financial Times. “This is a humanitarian crisis.”

Europe’s economic heavyweights have taken notice and are warning that renegotiating Greece’s debts – a pillar of Syriza’s populist platform – is off the table

At a keynote speech at the World Economic Forum, German Chancellor Angela Merkel was blunt saying countries had to have “the responsibility to shoulder one’s own risks.”

But momentum is gathering against the imposed austerity – which stems from 240 billion euros in bailouts in order to save European banks and international institutions laden with bad debt brought on by the 2007-07 financial crisis.

Unemployment in Greece hovers around 27% while foreign debt is more than 170% of Greece’s GDP, meaning that despite running a surplus the country is on its knees servicing its debt. For years, anger has been brewing that Greek tax payers are paying back debt to essentially save European banks.

A radical backlash is predicted in some of the most affected countries. Leaders from Spain’s leftwing Podemos Party – which four months after it was founded won more than 1.2 million votes in last year’s European Parliamentary elections – have been campaigning for Syriza to lead in Greece.

Podemos’s 36-year-old leader Pablo Iglesias recently took the stage at a Syriza campaign rally in central Athens. Speaking to reporters shortly before, he said that ordinary European citizens are pushing back against financial elites.

“I think our countries for some time have been colonies of the powers of the North and colonies of the financial powers,” Iglesias said. “And I think that we need national sovereignty and we need a president that defends the people, and I think Alexis Tsipras and Syriza are an example of that.”

Iglesias brushed away criticism that populist rhetoric could endanger Europe’s already fragile economy. “I don’t believe in threats in order to do politics. I think that hope is the best word in order to define the possibility of a change in Europe," he said.

"I think the wind of change is blowing in Europe and the name of change in Greece is Syriza.”

Independent economists across the spectrum are also weighing in on Greece’s debt burden as Syriza prepares to sweep the polls. “The current situation is unrealistic,” University of Oxford economics professor Simon Wren-Lewis said in an email.

“So although the Eurozone will be forced to transfer some income to Greece by, for example, reducing interest rates on debt still further, it could never realistically avoid this.”

Economist Mark Weisbrot of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC, sees ideological politics behind Europe’s austerity project. “Their main goal is the structure of these economies to change them to be something more like the U.S. with less of a welfare state, weakening labor bargaining power with labor law reforms,” Weisbrot told Occupy.com.

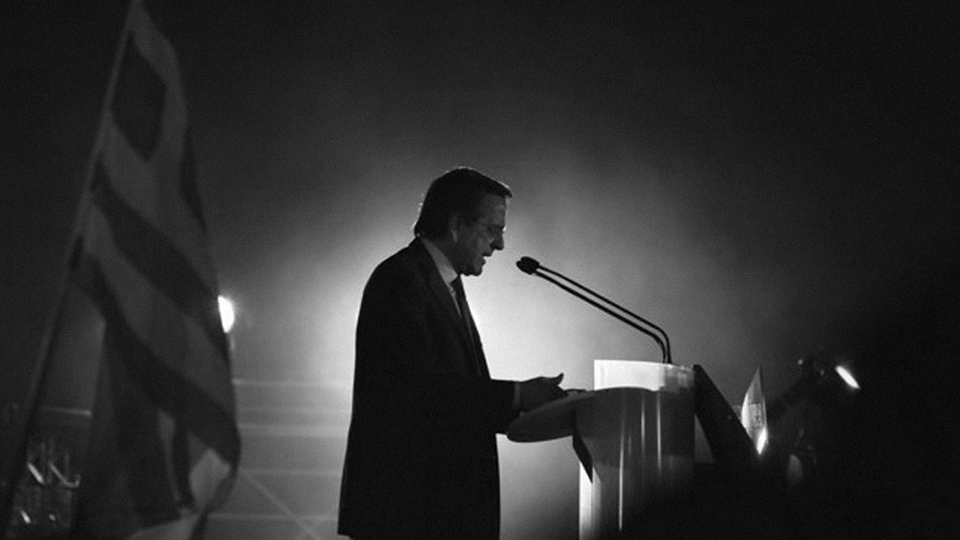

Greece’s current Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, whose center-right New Democracy continues to preach doomsday scenarios should Syriza come to power, has warned that a leftist victory would frighten away investors.

Meanwhile, the European Central Bank is fighting back in its own way. As Greek television carried a Syriza political rally, the ECB announced it would buy 60 billion euros a month in bonds in an effort to stimulate lending – a term called quantitative easing – in which banks try to encourage loans when interest rates are already at record lows.

But as Reuters reported, only a portion of the purchases would be the responsibility of the ECB. That means that if any euro zone country were to default, the debt would fall on national central banks.

Critics say that means the ECB could be preparing for the beginning of the end for Europe’s single currency.

“It is counterproductive to shift the risks of monetary policy to the national central banks,” former ECB policymaker Athanasios Orphanides told Reuters. “It does not promote a single monetary policy. This path towards Balkanization of monetary policy would signal that the ECB is preparing for a break-up of the euro.”

But if a Syriza-led Greece isn’t able to re-negotiate its foreign debt, would it really default and exit the Euro – which wags in Europe have coined as a Grexit?

“Grexit is not impossible, but it is only marginally possible,” Theodore Pelagidis, professor of economics at the University of Piraeus, told Occupy.com in an email. “It is a negotiating weapon for both sides.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments