OAKLAND, Calif. — As a longtime political activist, Malkia Cyril knows how smartphones helped fuel Black Lives Matter protests with outraged tweets and viral videos. But now Cyril is having second thoughts about her iPhone.

Is it a friend or a foe?

For all of the power of smartphones as organizing tools, the many streams of data they emit also are a boon to police wielding high-tech surveillance gear, allowing them to potentially track movements and communications that activists such as Cyril would rather keep private.

Such worries are driving a nationwide push by Cyril and other activists to train members of their movement in the tactics of digital defense — something they say is crucial with an aggressive new president who has displayed little sympathy for their causes.

Even as a leader in this drive, Cyril found herself startled one recent evening in a class called “Digital Security in the Era of Trump,” one of dozens of such sessions held since the November election. With the help of an app, she was able to see voluminous data recorded with the snapshot of a chocolate cupcake from an office birthday celebration earlier that day.

Among other information, the app showed Cyril’s exact location — marked by a giant red pin atop her downtown Oakland office — the moment she snapped the picture. It was the same information authorities could extract from the device or potentially even from the image itself if it were texted, emailed or posted on a social-media platform.

“That is crazy,” said Cyril, executive director of the Center for Media Justice and a member of the Black Lives Matter network, as she shook her head at the eerie precision of the data, which even included her altitude. Had the picture been taken at a clandestine meeting of protest organizers rather than a birthday celebration, their cover could have been blown.

Such concerns have fueled the nationwide spread of sessions such as this one in a fluorescent-lit classroom in downtown Oakland, where political activists over four hours learned how to encrypt messages, browse the Web anonymously and guard against accidentally revealing their locations when they want to operate in secrecy.

Their fears go beyond the change in the White House. The Justice Department’s announcement in April that it would review police reform agreements reached during the Obama administration has heightened concerns that the federal government is sharply curtailing its oversight of state and local police forces. Many departments in recent years have expanded their capacity to track cellphones, collect massive troves of video and analyze social-media postings, yet these police forces often operate with fewer restrictions than those in effect at the federal level.

Federal officials have warned for years that the spread of encryption and other defensive measures increasingly is thwarting legal surveillance of crucial targets, such as terrorists, criminals and child pornographers, making it harder to solve cases and prevent crimes. Officials also have lamented the rioting and other violence that has accompanied some political protests sparked by police killings, saying that the potential for spontaneous criminal activity can justify the monitoring of some large gatherings, even when the leaders intend only peaceful political protest.

The perception among political activists that they are unfairly targeted has fueled a new wave of technical training intended to blunt what they consider government overreach that threatens their constitutional rights to free expression.

But it remains unclear whether such a big, diffuse movement born on social media — Black Lives Matter began as the Twitter hashtag #BlackLivesMatter in 2013 — can maintain its spontaneous energy while curbing the use of technologies that expose activists to government surveillance.

“Now that this massive infrastructure has been handed to the Republicans and Trump, people are freaking out,” said Chinyere Tutashinda, national organizer for the Center for Media Justice. “People have this big, scary thought in their heads, but they don’t know what they can do. What can the local cops do? What can the feds do?”

Suing Over Surveillance

Fear that authorities use digital tools to aggressively monitor political demonstrations began before President Trump’s election. Two activist groups, the Color of Change and the Center for Constitutional Rights, sued the FBI and Department of Homeland Security in October to obtain records on the surveillance of Black Lives Matters protests and its leaders in recent years.

The lawsuit points to reported incidents in 11 cities, arguing that government monitoring of political protests with surveillance technology undermined free speech while serving to “chill valuable public debate about police violence, including the use of deadly force, criminal justice and racial inequities.”

Federal officials, the suit notes, used social-media tracking to monitor demonstrators after the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., on Aug. 9, 2014. Baltimore County police used similar technology during the protests that followed the 2015 death of Freddie Gray from an injury he suffered while in police custody; the FBI also conducted overhead surveillance flights as those demonstrations were overtaken by rioting.

The Justice Department and the Department of Homeland Security declined to comment for this article. The FBI issued a statement saying: “The FBI investigates activity which may constitute a federal crime or pose a threat to national security. Our focus is not on membership in particular groups but on criminal activity. As part of its work, the FBI uses a wide array of lawful investigative methods, each used only under appropriate circumstances, and always in accordance with applicable Attorney General’s Guidelines, the Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide, and the U.S. Constitution.”

Yet law enforcement officers faced with demonstrations in volatile political climates often struggle to assess when rioting or other violence might break out, said Ronald Hosko, a former assistant director of the FBI who is now president of the Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund, which raises money to defend officers accused of misconduct. Intelligence-gathering through digital and other tools allows authorities to evaluate threats and possible criminal activity, even when political leaders intend to lead peaceful, legal protests.

“That’s what law enforcement needs to be vigilant about, to find the way in,” Hosko said.

But activists recount a long history of authorities overstepping constitutional bounds because of fears of violence. Federal officials extensively surveilled the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, wiretapping the phones of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders of the movement.

Many activists say that, despite reforms, similar tactics continue. As recently as 2015, the Department of Homeland Security monitored a funk-music parade and an unrelated community parade in historically African American neighborhoods in the District, according to a report in the Intercept based on government records.

“The apparatus that has been handed over to Trump is something that has been around for 50, 60, 70 years,” said Cyril, whose mother was a member of the Black Panthers, a black nationalist group that once was the focus of intense FBI surveillance and disruption efforts.

The Center for Media Justice sponsored the class in Oakland and plans similar sessions in Detroit, Atlanta, Minneapolis and other cities in the coming months. Cyril considers the effort long overdue.

“Part of me is, ‘Why are we starting now?’ ” she said. “I’ve never felt safe.”

The Fear of Trump

The simple answer is: Trump. Or rather, the fear of Trump.

Although he has at times expressed worry about government overreach — including his unsubstantiated allegation in March that the Obama administration wiretapped Trump Tower during the presidential campaign — activists say they have little hope that the administration will move to curb its own capabilities. The president’s impassioned support of law enforcement, meanwhile, has convinced activists that he is not sympathetic to their concerns about questionable police shootings and other possible misconduct.

In August 2015, when Trump was a candidate for president, he was asked on “Meet the Press” about Black Lives Matter protests. Trump responded by invoking high crime rates in Baltimore and Chicago, saying, “We have to give strength and power back to the police. And you’re always going to have mistakes made. And you’re always going to have bad apples. But you can’t let that stop the fact that police have to regain some control of this tremendous crime wave and killing wave that’s happening in this country.”

Trump’s conservative Cabinet appointments, especially Jeff Sessions as attorney general, have deepened concerns, as has the Justice Department’s apparent moves to retreat from aggressive monitoring of state and local police departments — which political activists fear could embolden police departments to employ surveillance more aggressively.

Such worries run especially strong among African Americans, Latinos and other activists of color working to resist the administration’s initiatives on criminal justice, immigration and other issues.

Although laws and court precedents govern how and when surveillance tools are used, there remain broad legal gray areas as technology rapidly evolves. The Justice Department, for example, in 2015 began requiring that federal authorities get search warrants before using cellphone-tracking technology, a standard that requires demonstrating probable cause that a target has committed a crime. But the federal restrictions do not apply to state and local police forces, most of which have not adopted the standard.

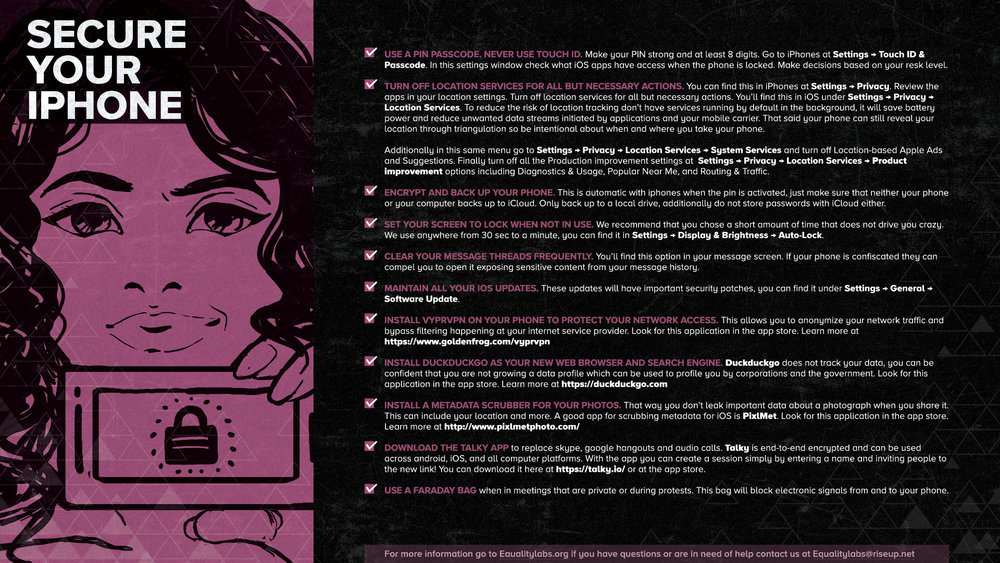

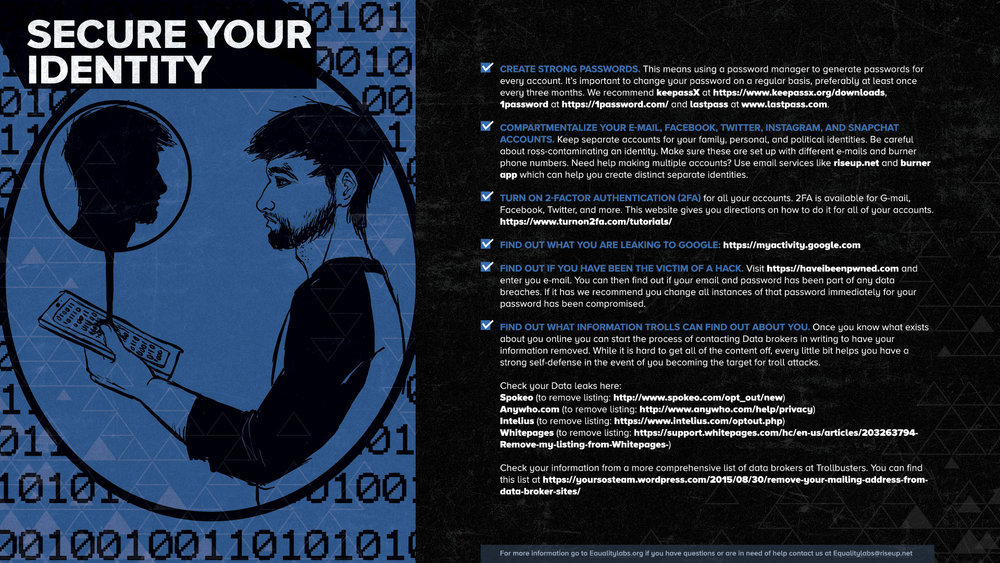

As concerns have grown since the election, Equality Labs, a human rights group that works in the United States and South Asia, has led dozens of digital-security training sessions, including the one in Oakland. Other groups, meanwhile, have increased the frequency of “cryptoparties” that teach how to encrypt messages, hard drives and other digital essentials that are vulnerable to surveillance.

“It’s this moment when, all of the sudden, people are very worried and suspicious of the government,” said Matt Mitchell, an African American security researcher who founded the New York group CryptoHarlem. “They feel like using these tools will give them some semblance of freedom and autonomy and ability to speak.”

Better security, however, has always carried costs, because the most vulnerable technologies also tend to be the most widely available and easiest to use. Emails and text messages are vulnerable to interception and can open the door to hackers. Social-media postings create streams of data that law enforcement authorities can monitor using powerful analytical software. And cellphones, no matter how advanced or primitive, continuously transmit location data in ways that surveillance gear can collect.

The more secure alternatives often require new technical skills or extra precautions, such as using the heavily encrypted Tor browser for surfing the Web more safely — if somewhat more slowly — than is possible with Chrome or Internet Explorer.

Cyril acknowledged that the push for tighter security might dampen or discourage some activists who are reluctant to change familiar habits. “There is a tension, but not one that can’t be overcome.”

The lead trainer this evening, Thenmozhi Soundararajan of Equality Labs, compared the techniques she was teaching to “safe sex” campaigns stressing the use of condoms to block HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Such measures, while not perfect, help guard against persistent dangers, she said.

“You should never use the Internet without protection,” she said.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments