As the United States begins to grapple with the issue of growing economic inequality, it should not ignore the widening income gap on American college campuses.

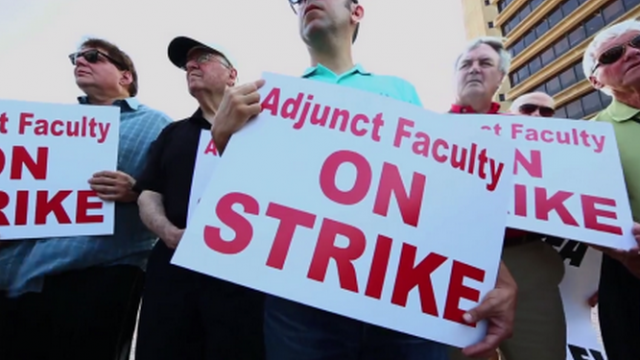

Some of the nation’s poorest people work at higher educational institutions, and many of them are members of the faculty. Oh, yes, there are still faculty members who receive comfortable middle class salaries. But most faculty do not. These underpaid educators are adjunct faculty, who now comprise an estimated 74 percent of America’s college teachers.

Despite advanced degrees, scholarly research experience and teaching credentials, they are employed at an average of $2,700 per course. Even when they manage to cobble together enough courses to constitute a full-time teaching load, that usually adds up to roughly $20,000 per year — an income that leaves many of them and their families officially classified as living in poverty. Some apply for and receive food stamps.

Adjunct faculty face other job-related difficulties as well. Lacking employment security of any kind, they can be hired to teach courses the day before classes begin — or, for that matter, not hired at all. They often receive no healthcare or other benefits, have no office space, mailboxes, or email addresses at colleges where they teach, and drive long distances between their jobs on different campuses. As the impoverished migrant labor force of its day, this new faculty majority deserves its own Grapes of Wrath.

By contrast, others on campus are doing quite well. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, forty-two presidents of private colleges and universities were paid more than a million dollars each in 2011 — up from thirty-six the previous year. The highest earners were Robert Zimmer of the University of Chicago ($3.4 million), Joseph Aoun of Northeastern University ($3.1 million), and Dennis Murray of Marist College ($2.7 million).

Unlike adjunct faculty, whose income, when adjusted for inflation, has dropped by 49 percent over the past four decades, these campus presidents increased their income substantially. Zimmer’s pay doubled, Aoun’s pay nearly tripled, and Murray’s pay nearly quadrupled from the previous year. The yearly compensation packages for eleven of the forty-two million-dollar-or-more private college presidents nearly doubled.

Furthermore, high-level administrative positions often come with some very substantial perks. At the University of Nebraska, top administrators are given free memberships in country clubs, as well as very expensive cars, like the Porsche driven by the chancellor of its medical center. At New York University, the trustees gave president John Sexton — whose university compensation in 2011 was $1.5 million — a $1 million loan to help him purchase a vacation home on Fire Island.

According to a New York Times article, Gordon Gee — the Ohio State University president who received university compensation in 2011-2012 of $1.9 million — was known for “the lavish lifestyle his job supports, including a rent-free mansion with an elevator, a pool and a tennis court and flights on private jets.”

Some have argued, of course, that top campus administrators genuinely deserve these kinds of incomes and lifestyles. But faculty and others are not so sure. At NYU, after the faculty voted no confidence in President Sexton’s leadership, the trustees convinced him to retire at the end of his contract, in 2016. At Penn State, where President Graham Spanier was the highest-paid public university president in the United States in 2011-2012 (at $2.9 million), he was dismissed in connection with the crimes of the former assistant football coach who was convicted in 2012 on forty-five counts of sexual abuse. Spanier is expected to stand trial on charges that he failed to report the crimes and tried to cover up what he knew. On other campuses, top administrators have been convicted of extensive fraud and embezzlement.

But even if one assumes that most campus administrators do a good job, why should there be a widening gap between their incomes and the incomes of those who do the central work of the university: the faculty?

Furthermore, why should there be an ever-growing number of administrators — presidents, vice presidents, associate vice presidents, assistant vice presidents, provosts, associate provosts, deans, associate deans, assistant deans, and a myriad of other campus officials? Between 1993 and 2009, the ranks of campus administrators expanded to 230,000 — a growth of 60 percent, ten times that of the tenured faculty.

Not surprisingly, a recent report by the American Institutes for Research revealed that, in 2012, there remained only 2.5 instructional or nonprofessional support employees for every administrator. As colleges and universities are flooded with administrative officials, is there no longer a role for those who do the teaching and research?

Perhaps the time has come to redress the balance on campus by cutting the outlandish income and number of administrators and providing faculty members with the salaries and respect they deserve.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments