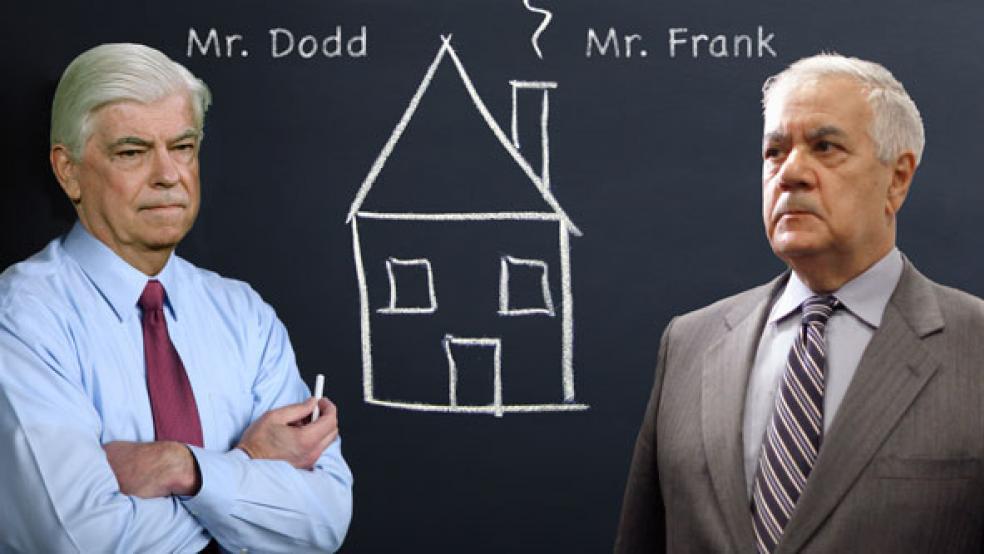

Not content with their fruitless assault on Obamacare, one of President Obama’s two signature achievements, Republicans are now staging a similarly symbolic challenge to the other. In June, the House passed a measure that would significantly pare back the Dodd-Frank financial reforms. While it’s highly unlikely to become law, the bill promotes bogus and dangerous arguments for unregulated finance.

Passed in 2010, Dodd-Frank was Congress’s response to the 2008 financial crisis, which was a product of Wall Street excess more than the naïve homebuyers who are often blamed for it. The idea was partly to rein in the inordinate risk-taking by large financial institutions that pose a hazard to innocent bystanders. There’s a link here: When out-of-control financial systems crash and burn and the economy contracts in response, as happened in 2007-09, millions of people lose jobs. Pre-Obamacare, that meant losing your health insurance.

The assault on Dodd-Frank is being led by House Financial Services Chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-Tex.), who, to no great surprise, gets much of his campaign money from the financial-services industry. The Hensarling-drafted Financial CHOICE (Creating Hope and Opportunity for Investors, Consumers and Entrepreneurs) Act, which passed the House in June, would do several big things that are in the interests of financial institutions but not of most other folks. (The Senate is considering its own version of Dodd-Frank rollback.)

Among its more critical features, the bill would:

-

Replace Dodd-Frank’s Orderly Liquidation Authority, a process for closing a failing institution without setting fire to the entire financial system);

-

Retroactively repeal the authority of the law’s Financial Stability Oversight Council to designate firms “systematically important financial institutions“ (SIFIs);

-

Repeal the Volcker Rule, which generally forbids banks from making risky bets with their own money (“proprietary trading”) while benefitting from federal deposit insurance;

-

Effectively strip the law’s Consumer Financial Protection Board (CFPB) of its authority and make its director a political appointee subject to removal at the president’s whim.

So much for regulatory independence.

Hensarling pitches the CHOICE Act with predictably populist language: "If we want strong economic growth and more freedom, we must empower Americans, not Washington bureaucrats."

This sort of mindless platitude calls for analysis. First, since when are federal employees not Americans? Second, how would non-bureaucrats prevent irresponsible SIFIs from wrecking the financial system? Third, how would removing constraints on gigantic financial institutions “empower” Americans, aside from the Americans who run large SIFIs? “Strong growth and more freedom” for whom?

Like most opponents of Dodd-Frank, Hensarling gets the logic of financial markets exactly backwards: Finance is an inherently risky enterprise involving inherently risky personality types, and Washington bureaucrats, also known as regulators, are often the only adults in the room.

There are plenty of disingenuous rationales for paring back Dodd-Frank. One is that the law has curtailed bank lending and hurt the economy. Not true, according to several analyses including this one. The latest data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp, the chief regulator of the biggest banks, shows that they don’t seem to be suffering very much, either.

Then there’s the argument that Dodd-Frank compliance rules are hurting community banks. But that’s far from obvious. If anything is crimping bank lending, it’s the banks themselves, according to an intriguing and under-reported letter to the Senate Banking Committee from FDIC Vice Chairman Thomas Hoenig, who says that if the 10 biggest U.S. banks didn’t spend 99 percent of their net income on dividends and share buybacks – a deceptive way of boosting the banks' share price – they’d have an additional $1 trillion (equal to more than 5 percent of national output) free for lending.

Another Wall Street trope is that Dodd-Frank (indeed all regulation) creates uncertainty, which is always a problem for financial markets. But the law is a seven-year-old fact. A serious threat of repeal is what would create uncertainty. Others argue that the Volcker Rule is unnecessary because proprietary trading by banks has fallen off since the financial crisis.

Francis Creighton, head of the Wall Street lobbying group Financial Services Roundtable, told CNN earlier this year that “Prop trading is gone. We're not looking for it to come back.” That’s a bit like saying the wolves are no longer at the door, so let’s take down the fence.

There may be parts of Dodd-Frank that need revising, even repealing. But that’s mere detail. The big question has to do with the nature of financial crises, which in the absence of prudential regulation are not occasional anomalies but inevitabilities. The best-known exponent of this idea is the late economist Hyman Minsky, whose “financial instability thesis” holds that unless they’re restrained in some fashion, financial institutions necessarily make increasingly risky bets (higher returns generally require higher risk), rather like a reckless driver finding out the hard way how fast is too fast.

If an institution is big and well-connected enough, its failure, or even a rumor of failure, can generate waves of fear that shut down the financial system and wreck the real economy, where average people live. This is essentially what happened in 2008. The looser Congress makes the regulatory leash, the riskier SIFIs will be. In a relentlessly competitive realm where every firm is judged on quarterly earnings and pressured by merciless shareholders, there is little choice. As Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince put it on the eve of the 2008 flameout, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

Dodd-Frank, however imperfect, isn’t just about protecting average folks from reckless, predatory finance. It’s also about protecting Big Finance from itself. The House assault on the law probably won’t succeed this time around, but the propaganda behind it promotes a dangerous myth that even Alan Greenspan has renounced: that banks can regulate themselves. That idea will have consequences when memories of 2008 fade, as you can be sure they will.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments