This is the 18th installment in a series about extending the Green New Deal to confront multiple global crises. Read Part I (Deconstructing environmental racism), II (Rural renewal), III (Upcycle the war machine), IV (GND manifestos), V (No oil bailouts), VI (No corporate ecocide), VII (Defund the police), VIII (Zero Covid approach: NZ), IX (Finnish equality lessons), X (Denmark stops drilling), XI (Costa Rica rewilding), XII (Indigenous justice), XIII (Free public transport) XIV (No borders), XV (Chile's democratic revolution), XVI (Undermining neoliberal dogma), and XVII (Climate Litigation).

As President Dwight Eisenhower once said: “Growth is a substitute for equality of income. As long as there is growth there is hope, and that makes large income differentials tolerable.”

In power between 1953 and 1961, Eisenhower is often praised because wages rose and living standards improved in the U.S. during that period. Yet the 1950s were also the time when growth became a primary goal following the invention of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the 1930s.

The late invention of the concept of GDP is startling considering that growth is largely unquestioned today – even by those with very different political perspectives.

Yet promised dreams of endless growth have caused and driven today's globalized crisis. Pursuing growth has expanded everything from income inequality to the ever more deadly climate crisis. These assertions and a comprehensive critique of growth can be found in the must-read new book The Future Is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism (Verso, 2022), written by Matthias Schmelzer, Andrea Vetter and Aaron Vansintjan.

The book sets out why in order to reach a universally just and ecologically viable future we need to shift into degrowth. Crucially, too, it signposts how to get there.

We need degrowth beyond capitalism

According to the authors, we have overshot five planetary boundary thresholds that will “trigger unpredictable ecological breakdown. These are irreversible climate change, mass species extinction, excessive land use, the overburdening of the nitrogen cycle and pollution by novel entities including plastics and chemicals.” It is just one of many foreboding reality checks in a growth-based capitalist system that threatens everyone and everything in its path.

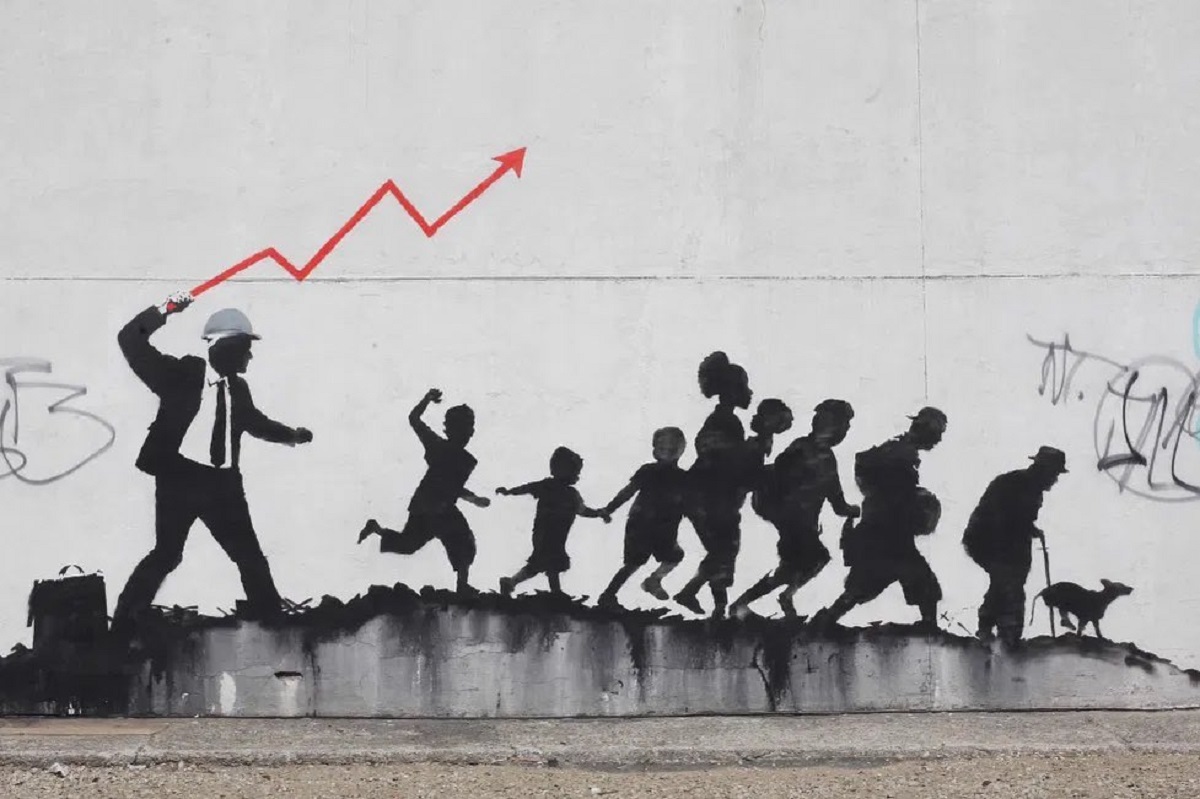

That we cannot have infinite growth on a finite planet is a tension-laden statement. On the one hand, it makes sense. Yet on the other hand, the majority of people live in a socio-political state in total contradiction with this statement. Against this, degrowth is a provocation: a “missile word.”

During this century – especially as the ecological and economic crises increase in their severity – there has been more interest in degrowth. In turn this causes more ungrounded counterattacks by those advocating the status quo. To remedy this, the book is clear what degrowth is not: it is not a financial crash, nor a recession.

Rather, the authors explain that degrowth should “enable global ecological justice,” reducing what we use to a way that is “ecologically sustainable in the long term and globally just.” Secondly, degrowth should create social justice, self-determination and a good life for everyone – while transforming institutions and infrastructure to make this reality.

Thus degrowth is about undoing systemic crises for universal justice. Is it compatible with the Green New Deal? Yes and no, but it needs to be.

A Green New Deal without growth?

The Future Is Degrowth offers a direct provocation to the Green New Deal movement. The authors describe how the GND both offers a potential greenwashing tool for green capitalism, yet it can likewise be used to address the multiple systemic crises we face and create a universally good future. In short, the Green New Deal needs to shrink and transform the economy to within ecological limits – as the book sets out.

The way we think about automobiles is one way to differentiate a greenwashed GND from one based on degrowth. The former would be about swapping motorcars with electric ones. The latter is about sharing the finite resources – such as lithium – ethically via decent free public transport.

The book’s critique and bridge-building ultimately asks the question: what does the Green New Deal mean?

The New Deal – the slogan's inspiration – included massive public investment by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to counter the Great Depression in the 1930s. Thus is the New Green Deal about public investment to kickstart the economy? As the book makes clear, the same infusion cannot happen today. Instead, we need some green investment but overall must shrink the economy and redistribute wealth independently from growth.

Yet we can interpret the 1930s differently. Today we need to change everything for the common good, as they did a century ago. But these cannot and will not be the same changes, as they in part led to where we are now, since the New Deal failed to deal with many structural oppressions.

A central pillar of the book – and the degrowth movement – is also degrowing work (as in: labor) The next part in this series will explore the social value of work, both as a means and end.

Theory of Change

Ultimately, The Future Is Degrowth sets out a political theory of change that is a space ripe for collaboration with the GND. The authors suggest transformative change is about non-reformist reforms, for instance free education, Universal Basic Income, free public transport and so on.

It is also about interplaying with counter-hegemonic social movements, such as abolition and migrant rights struggles; anti-extractivism direct action; and climate litigation alongside many other examples. For instance, Nowtopias are places that show we can do things completely differently, say a democratic municipality, a social space, or even an autonomous region.

The scope for overlap between the GND and degrowth represents political pathways that are symbiotic. Both Roosevelt's New Deal and the spearheading of the Green New Deal as a mainstream idea by, among others, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, show how different political strategies can coalesce. In the 1930s, unions – which held massive counter-hegemonic power – firstly put the demands on the table. They then resisted counter-attacks by the corporate establishment against all the non-reformist reforms that made up the New Deal.

Ocasio-Cortez’s personal story offers another example. She was inspired to eventually push the GND (a set of non-reformist reforms, in the language of the authors) after visiting Standing Rock, itself a Nowtopia of indigenous sovereignty and power, and also a focal point of the counter-hegemonic collective power taking direct action against fossil fuel extraction.

Many GND advocates have a narrower theory of change, for instance, their focus is getting the right people into power. Often, they suggest that the energy and economic transition is about less, not more, transformation. Those people need to read this book.

As the authors argue, a future with a Green New Deal that does not shift away from endless growth will not last. Furthermore, to make any change against the powers-that-be, the movement needs to be intersectional and as broad as possible.

Above all, today’s New Deal must be made with, and by, the multitude – that is, everyone – and safely dispose of ideas like growth while replacing them with other ideas like ecological global justice.