It would be a severe mistake to reduce the Greta Gerwig-directed ‘Barbie,’ which is currently dominating the summer box office, to a hot pink toy marketing campaign. On its surface, ‘Barbie’ contains all the right ingredients for a kid-friendly celebration of Mattel’s iconic toy. But ‘Barbie’ also contains an incredibly nuanced, thought-provoking message about the devastating ways patriarchy affects both sexes.

The star-studded summer blockbuster has been lauded as a feminist film. Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro declared the film to be anti-men in a 43-minute review that was widely ridiculed after he burned Barbie dolls on camera in protest of the movie’s messaging. But when my girlfriend and I watched the film in a local theater last week, I noticed that 'Barbie' is not just pro-women; it’s also very pro-men.

Barbie’s accessible approach to feminism

Ultimately, ‘Barbie’ understands its role as a Hollywood blockbuster aggressively marketed to young audiences. If a viewer chooses, they could simply enjoy the film for its homage to the Barbie brand, its flashy pink glittery aesthetic, its witty nonstop one-liners, or for its wealth of fun song and dance numbers. The film’s only noticeably on-the-nose moments are when Will Ferrell, who plays a zany Mattel CEO, calls Barbie a “jezebel” and tells her to “get in the box,” and when America Ferrera – who plays Gloria, a hard-working single mother stressed over the growing distance between her and her rebellious tween daughter, Sasha – delivers a fantastic monologue about the challenges women face in modern society:

"It is literally impossible to be a woman. You are so beautiful, and so smart, and it kills me that you don't think you're good enough. Like, we have to always be extraordinary, but somehow we're always doing it wrong.

You have to be thin, but not too thin. And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin. You have to have money, but you can't ask for money because that's crass. You have to be a boss, but you can't be mean. You have to lead, but you can't squash other people's ideas. You're supposed to love being a mother, but don't talk about your kids all the damn time. You have to be a career woman but also always be looking out for other people. You have to answer for men's bad behavior, which is insane, but if you point that out, you're accused of complaining. You're supposed to stay pretty for men, but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or that you threaten other women because you're supposed to be a part of the sisterhood.

But always stand out and always be grateful. But never forget that the system is rigged. So find a way to acknowledge that but also always be grateful. You have to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line.

It's too hard! It's too contradictory and nobody gives you a medal or says thank you! And it turns out, in fact, that not only are you doing everything wrong, but also everything is your fault.

I'm just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us. And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don't even know."

But when watching the film from a feminist lens, the subtext of the script urges readers to critically examine both the institution of patriarchy and the solutions to correcting it. And surprisingly, its message to men is that we have just as much of a role to play in the fight against patriarchy as women, if not more so: Because as men, we have the challenge of battling it not just on behalf of the women in our lives, but also on behalf of our fellow men who are preyed upon by the same institution.

Barbie’s arc: From oppressor to victim of patriarchy to victor

One of the moments of ‘Barbie’ I didn’t expect was how the film rendered Barbie as not a blameless woman raging against the institution of patriarchy, but rather as an oppressor in her own right. All the Barbies in Barbieland willfully turned a blind eye to the inequality and injustice that were everyday realities to Ken (and Ken’s buddy, Allan). And Barbie’s selfish concern about her own privilege and status early on in the film is what creates the central tension of the plot.

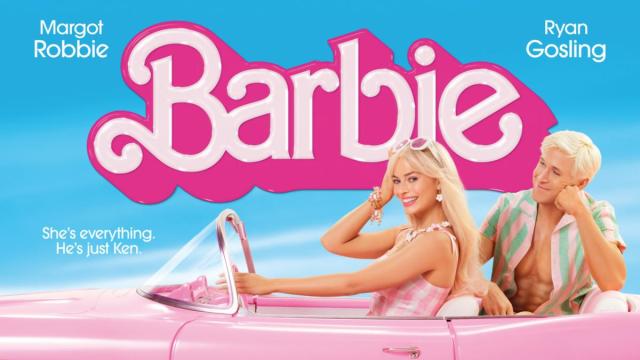

In Barbieland, Ken is an oppressed minority, living the life of a second-class citizen. This is exemplified in the film’s tagline, “She’s everything. He’s just Ken.” Ken has no job other than “beach” (not lifeguard, just “beach”). Ken’s only agency is in his proximity to Barbie, who is clearly at the top of the Barbieland hierarchy. Meanwhile, the Barbies run every branch of government, live in opulent mansions, drive luxurious cars, and monopolize the economy, working every job while the Kens (and Allan) stand around and wait to be acknowledged.

When Ryan Gosling’s Ken asks Barbie if they can spend time together “as boyfriend-girlfriend,” Barbie tells him, "I don't want you here." She adds that doing so would be impossible anyway, because it’s also girls’ night.

“Every night is girls’ night, from now until forever,” Barbie says to Ken with a big smile, before going back into her Dream House with all of the other Barbies and squealing with glee while Ken stands alone and looks on. At one point in the film, when a character from the real world asks Barbie where Ken lives, Barbie realizes Ken is homeless. And she doesn’t care.

Ken eventually follows Barbie into the real world. While Barbie has a conversation with Sasha (who calls Barbie a "fascist" who has been "making women feel bad about themselves ever since you were invented"), Ken discovers a world where men run everything, and where he finally has respect. Ken becomes obsessed with both patriarchy and horses, which are a stand-in for symbols of masculinity like guns and trucks (Ken refers to horses as “man-extenders”). While Barbie goes to the phallic-shaped Mattel headquarters to fix her flat feet, cellulite, and thoughts of death, Ken goes back to Barbieland and implements patriarchy. He turns Barbie’s Dream House into Ken’s “Mojo-Dojo-Casa-House” and plans to rewrite Barbieland’s constitution to center society around Ken, which he dubs a “Kendom.” The Barbies who used to be president and who sat on the Supreme Court now wear cheerleader outfits and serve the Kens “brewski-beers” while they play sports.

It’s important to note that even though Ken was an antagonist, he was also a revolutionary. Ken successfully organized enough like-minded Kens to radically re-orient society and overthrow their oppressors. However, Ken chose not to have a revolution of equality, but a revolution of supremacy. His revolution was driven by spite: The existing hierarchy was maintained, but with the Kens as the new oppressors. This is an excellent cautionary message to activists to not simply get swept up in radical opposition to the status quo, but to have the same energy for solutions and new systems.

When Margot Robbie’s Barbie (“Stereotypical Barbie”), Gloria, and Sasha return to Barbieland and see it has turned into Kendom, Barbie becomes despondent. In one uniquely memorable scene, Barbie folds up on herself, saying she's going to wait for someone to save her. Sasha tells Barbie that no one is coming to save her; she has to save herself.

When Barbie laments that her world will never be perfect again, Sasha tells her something a lot of activists need to be reminded of:

"It won't be perfect," Sasha says. "But it can be better."

After Barbie gets motivated again, the gang joins up with Kate McKinnon’s Barbie (“Weird Barbie”) to de-program the other Barbies captive to patriarchy. They then organize to divide the Kens against each other to make them easier to conquer. They start the plan by sitting at a campfire on the beach while Ken plays an acoustic rendition of “Push” by Matchbox 20. The Barbies then pull out a pink phone to text another Ken and sit by his campfire instead. This enrages the Kens, who break off into camps and have an epic battle on the beach. This battle coincidentally falls on Election Day, and the Kens all forget to vote to amend the Constitution to make patriarchy permanent.

The battle between the Kens is particularly illuminating: They begin by punching and kicking and throwing objects and tackling each other, but then the fight choreography transforms into elaborate song-and-dance choreography, and ends with the Kens hand in hand. This is a powerful message to men that we don’t need to dominate and compete with each other: We can collaborate and cooperate, and still have our own identities.

At the film’s conclusion, the Kens all exclaim “Ken is me!” when realizing they don’t have to be faceless background characters, and that they are all unique individuals who aren’t defined by their outfits, their girlfriends, or “beach.” The “Ken is me” moment was reminiscent of the 1960 film ‘Spartacus,’ in which Spartacus’ fellow revolutionaries all declare “I am Spartacus” to the Romans, not only to protect Spartacus’ identity, but also in a gesture of universal solidarity and identification with Spartacus’ movement for freedom. Ryan Gosling’s post-patriarchy Ken wore a hoodie that read “I am Kenough,” and that’s a message a lot more men need to hear.

The Kens – and Allan – are also victims of patriarchy

After the epic Ken battle, the Barbies dismantle patriarchy, and the Mojo-Dojo-Casa-House is the Barbie Dream House again, Ken sobs to Barbie while she comforts him.

“Once I found out the patriarchy wasn’t about horses I lost interest anyway,” Ken says through tears.

This line is funny, but it’s also true: Patriarchy is a violent, repressive institution that enforces the supremacy of men via the subjugation of women, but that cleverly disguises its true nature by cloaking itself in symbols like guns, sports, and trucks (or horses) to enlist men to be unwitting acolytes for its continued existence. Oppressing the Barbies didn’t make the Kens happier or more complete, nor did the female utopia Stereotypical Barbie lived in at the beginning of the movie – that led to her having thoughts of death, cold showers, burnt toast, cellulite, and flat feet – fulfill Barbie. It’s only through everyone having their own equal opportunities to self-actualize when we can have happiness in our own lives.

But this review wouldn’t be complete without discussing Ken’s buddy, Allan (played brilliantly by Michael Cera). While some critics think it might be implied that Allan is gay, he never outwardly shows romantic interest in any of the Kens, despite their fashionable clothes and chiseled abs. Even though the Kens have Barbies as girlfriends, Allan has no boyfriend or girlfriend, and is forever alone, because even though there are many Barbies and Kens, there is only one Allan. In fact, Allan’s nature as an outcast in relation to both the Barbies and the Kens suggests something far more sinister: Allan may be an incel (short for “involuntarily celibate”) mass shooter.

Of course, guns don’t exist in Barbieland, and aside from the Ken battle at the end, there’s no violence in the film aside from one notable exception. When Stereotypical Barbie and Gloria are driving to the real world, Allan pops up in the backseat, wanting to leave the hyper-macho Kendom for something better. Despite Allan’s quiet, non-confrontational nature, he snaps when Kens clad in orange construction vests approach to stop Barbie.

Allan suddenly breaks out into a karate-fueled rampage, punching and kicking every Ken he sees before choking one out with a shovel handle. He charges at the other Kens but they run away. Despite his outburst, Allan remains unseen and unheard besides one brief acknowledgement from Gloria, and almost immediately goes back to being an afterthought through the end of the film. Allan’s arc suggests that his constant isolation and marginalization has led to a deep inner rage that can only be satiated through acts of mass violence.

The isolation and loneliness Allan feels is something lots of men can identify with, especially following the Covid-19 pandemic. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy released a report in May delving into the “epidemic of loneliness and isolation” that is particularly prevalent in men. In a 2023 survey, just 30% of men said they had a conversation with a close friend in which they shared personal feelings. Only 27% of men said they had at least six close friends, which is half the percentage recorded in the 1990s. 15% of men said they had no close friends at all.

One trait of patriarchy is that it isolates men, encourages them to be emotionally stunted, and discourages self-care through therapy. This often leads to women reluctantly performing a lot of emotional labor in their own heterosexual relationships. In her 2011 book “Deep Secrets: Boys’ Friends and the Crisis of Connection,” researcher Niobe Way explores how young boys go from having male best friends whom they love in their childhood years, to becoming alienated from their male friends through internalized homophobia.

“As boys enter manhood, they start using the phrase ‘no homo’ following any intimate statement about their friends, and they begin to say they don’t have enough time for their male friendships, even though they continue to express strong desires for having such friendships,” Way writes. “Boys know by late adolescence that their close male friendships, and even their emotional acuity, put them at risk of being labeled girl, immature, or gay.”

The theory that Allan’s violent outburst at the Kens is a byproduct of patriarchy isn't so far-fetched, as research confirms the link between toxic masculinity and mass shootings. In 2019, Mother Jones analyzed the perpetrators of more than two dozen mass shootings since 2011 and noted that a significant number of them contained at least one component of patriarchy: 86% of mass shooters studied had a history of domestic abuse; a third had a history of stalking and/or harassment, and half of those shootings specifically targeted women. A separate study of mass shooters between 2014 and 2019 confirmed that misogyny plays a strong role in acts of mass violence, with their data showing that roughly two-thirds of mass shooters carried out a form of domestic violence.

Aside from its exploration of the inherently violent and oppressive nature of patriarchy, ‘Barbie’ is ultimately a fun, lighthearted film that’s appropriate for both young and adult audiences. But its biting commentary on patriarchy is as refreshing as it is urgent. Barbie may be everything, but we are Kenough. I rate this film 9 out of 10.

(This article was written during the WGA/SAG-AFTRA strike. The film being reviewed wouldn’t exist without the work of dedicated writers and actors. Spoiler alert: Details of the plot of ‘Barbie’ are described above.)

Carl Gibson is a freelance columnist whose work has appeared in CNN, USA Today, the Guardian, the Washington Post, the Houston Chronicle, Barron’s, Business Insider, the Independent, and NPR, among others. Follow him on Bluesky @crgibs.bsky.social.