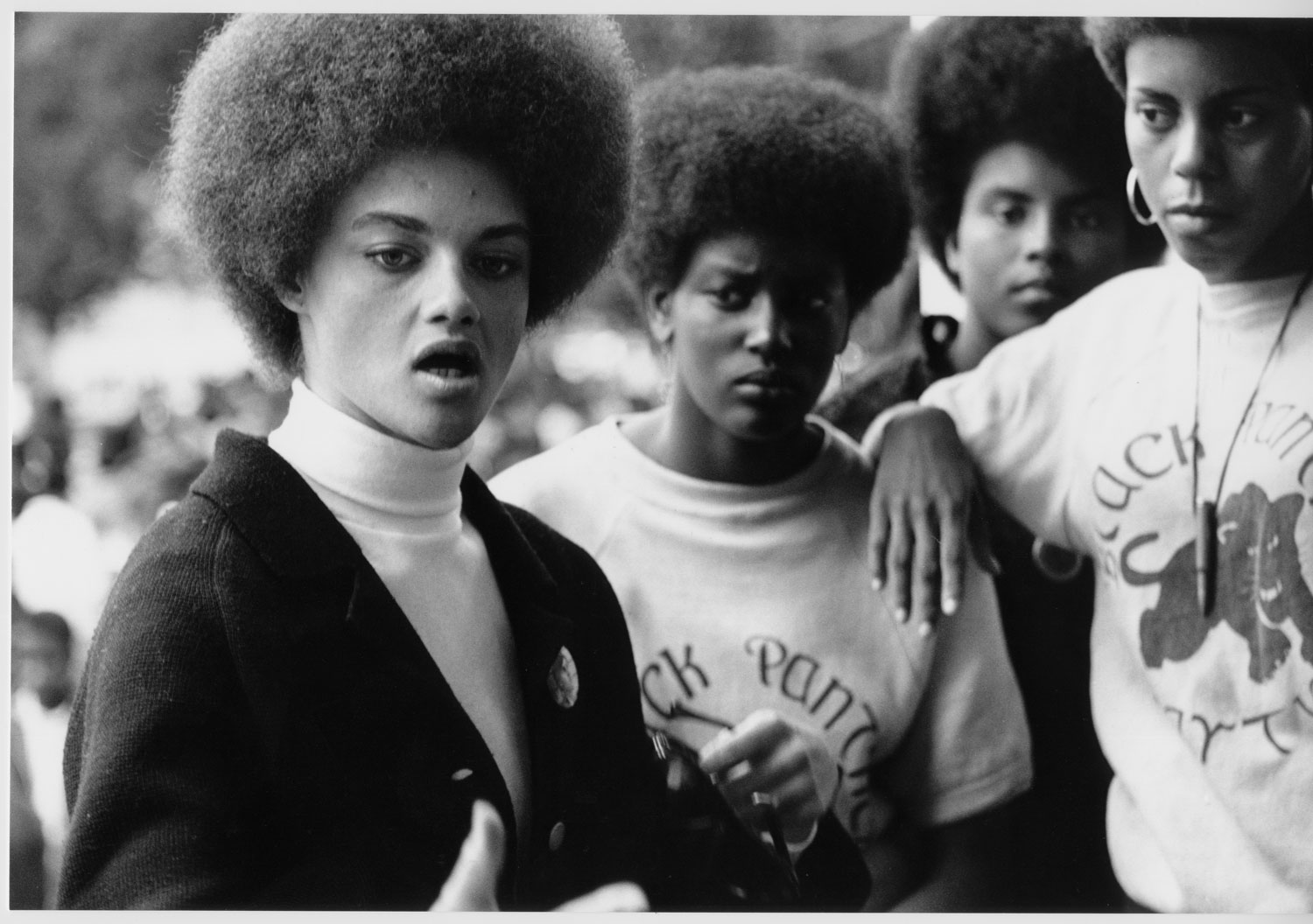

©2014, Stephen Shames

Near the end of a three-day reunion and celebration of the Black Panther Party in October, a sixty-something African American woman took me aside and whispered in my ear. I’d been taking copious notes furiously all day everyday and Barbara — the perky woman with the big earrings — seemed to want me to know something really important.

“The best stories can’t be told,” she explained. “Even after all these years, the truth is too dangerous to be shared.”

That may be so and yet day after day the Panthers who took the podium at the Arlene Francis Center in Santa Rosa, California, told riveting stories about the origins of the organization in Oakland in 1966, the decision to reject Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s non-violence and to arm themselves, and the war that was waged against them by the FBI and by police departments all across the country.

By 1970, Panthers had been killed in shoot-outs in Los Angeles, Oakland and Chicago, where the police murdered Fred Hampton and Mark Clark while they were asleep. Public outcry was swift and loud. Young black men rushed to form chapters around the country, but the lost leadership was irreplaceable. By 1970, Eldridge Cleaver, the charismatic Minister of Information — and author of the bestseller, Soul on Ice — was living in exile in Algeria and largely out of commission, and the organization’s two founders, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were tied up in legal battles in courtrooms from coast to coast.

Newton and Cleaver are, of course, no longer alive, and so couldn’t attend the Panther reunion — except in spirit. Seale, who lives in Oakland and who has written a cookbook and become a stand-up comedian, promised to attend and didn’t. That was disappointing, though not tragic. Everyone who spoke, including the event’s main organizer, Elbert “Big Man” Howard and nearly all the Panthers who attended, had not been among the top leaders in the organization.

Surprisingly, the task of carrying on the Panther legacy had fallen into the hands of men who had carried out orders, not given them. Yes, Panther leaders gave orders. Rank and file members were expected to carry them out — or be expelled. And yes, almost all of the speakers at the reunion and celebration were men, though women were in the audience.

There was far too little information about sex, sexism and gender in the Panthers, and perhaps far too few suggestions about how organizers and activists could learn from the Panthers and adapt their strategies to the present. Speakers criticized the generation of young blacks in Oakland and elsewhere around the country: they were disrespectful of their elders, they dressed and spoke rudely and crudely, and they had lost the oral tradition that had sustained the original Panthers and connected them to their parents and grandparents — or so they said. To apply lessons from the Panther past one had to read between the lines and extrapolate.

At the start of the event, “Big Man” looked out at the crowd of about 100 people and said, “As we come to the end of our own road, and look back at those who didn’t make it, we know that young people will carry on and do what needs to be done.” He added, “I’m here to support you in anyway I can.”

Neither Big Man nor any one else drew direct inferences from then to now, or offered specific ways that young people might carry on. Perhaps that would have been too much to expect. In fact, one attendee — a white woman radical from the Vietnam era — suggested that that would have been inappropriate. “It’s not the role of the Panthers to tell young people today what they ought to do,” she said. “It’s up to this generation to decide what forms of protests to adapt and how to implement them.”

What was valuable about the event — at least from my point of view — was that it was thoroughly integrated. Participants and audience members were both black and white. The Panthers had always committed themselves to making alliances with white radicals and they had not given up on that strategy — or, if “strategy” is too strong a word to use today, then “approach” will do. The point of the reunion and celebration was to honor the achievements of the past, not to ignite protest now.

The Panthers have no blueprint for protest, except to preserve their own history and to encourage young people today, both of which are vital factors. Without a sense of history and continuity, movements flounder.

White radicals from Berkeley who attended the event said they had not been in the presence of so many blacks since the 1970s. Indeed, the cordiality between the aging Panthers — “Big Man” is 75, for example — and the aging white radicals was remarkable. If the Panthers didn’t offer a blueprint for revolution for the 21st century, their candor about their own history was inspiring.

Behind the scenes, there was criticism and self-criticism, but the meetings that were open to the public were not exercises in public flagellation, much as they were not exercises in nostalgia. Here was an organization — or at least a group of survivors — who showed little interest in berating themselves and one another, seemed disinclined to stroke their own egos, and who were not, for the most part, promoting and selling their own books, records and tapes. (Panther T-shirts and memorabilia were on sale, but there as much free stuff — including food — as there was merchandise with a price tag.)

Of all the speakers who talked about the past, perhaps the most dynamic and the most informative was Aaron Dixon, the co-founder of the Seattle chapter of the Panthers and a Green Party candidate for the U.S. Senate in 2006. Dixon described the Panther decision in 1968 to “retaliate” for the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — decision that led to a shoot out with the Oakland police and the death of Bobby Hutton, a 17-year-old who was the first recruit to the Party.

Dixon, who was 19 and a college student, attended Hutton’s funeral. Soon afterward, he told Bobby Seale he wanted to start a Panther chapter in Seattle. Seale told him, he recalled, that every Panther had to have two weapons: 2,000 rounds of ammunition, and had to read and study two hours a day everyday and to attend political education classes. “These mothers were serious,” Dixon told the audience.

©2014, Stephen Shames

He went on to explain: “I remember a night in Oakland two weeks after Hutton’s funeral when you could cut the tension in the streets with a knife. I had my hand on my gun and all the other Panthers had hands on their guns. The police were armed, too, of course, but they were clearly afraid. So was everyone in the neighborhood. People thought there was going to be violence and raced home. The only people who didn’t leave the scene were the Panthers and the prostitutes. We stood our ground and the police backed down. That was my baptism of fire in the Black Panther Party.”

Dixon went on to describe his own role in the Seattle chapter, the development of the Panther free breakfast program for children, Bobby Seale’s campaign for mayor of Oakland — and the switch from guns to electoral politics — and Huey Newton’s decision to dismantle the organization in 1979. “It was hard not to be a part of the Panther family anymore,” he said. “People were traumatized by the break-up. Some even committed suicide.”

Dixon touched on the flaws of the Party, without dwelling on them. “We all had baggage and issues,” he said. “We did the best we could.” When a member of the audience asked him, “What do you say to young people today?” he replied, “That’s a good question. I’m not sure. I know that in the old days we had a culture, that we were close to history, and that we respected older people. That doesn’t exist anymore.” He also insisted, “We have to get back to community. We need to have a system of cultural values and we need to revive the kind of extended family structure that the Panthers offered.”

Not all of the speakers dwelled on the past. Emory Douglas, 70, described his own world travels and his connections today to political movements around the world, especially in Chiapas. The Panther Minister of Education from 1967 until 1980, Douglas’s artwork appeared in every issue of The Black Panther, the newspaper that had a circulation of about 140,000 in 1970 at the peak of the organization.

When I told him that someone who saw his art — which is rife with images of violence — might think that he was a violent person, he tossed back his head and laughed. In front of the audience and at the end of the three day reunion and celebration, he noted, “I’m not going to talk about me, but about the ways that the art I made created links to people around the world — in Polynesia, the Middle East, and in Mexico. Everywhere I’ve been, people have wanted to learn how to integrate art into politics.”

Douglas showed slides of the Zapatistas in Chiapas where he and his daughter worked side-by-side with young Zapatista artists, who often find inspiration in Mayan culture. One slide depicted a banner with a large red star and the words, “I am we.” Douglas’s daughter talked about the similarities between the Panthers and the Zapatistas – they both were armed and both were rooted in the community - and the ways in which the Zapatistas integrate art into their movement. They have a slogan she said: “Before there was I, there was we and we were one.”

That slogan may sum up the Panthers more than any other, though speakers at the reunion often repeated the popular Panther cry, “Power to the People.” The Panther legacy, Douglas suggested, is alive today around the world, though not as anyone in the party might have predicted in 1966 and 1967 when it shook up the American political landscape. No one imagined the Zapatista movement and no one imagined the links between the Panthers and the Zapatistas, or the living connections between Emory Douglas and the artists in the jungle of Chiapas.

Where ideology often gets bogged down, art seems to soar, and where history books fail to capture the energy of the past, oral history can bring it alive. Indeed, every movement needs its storytellers, artists, and writers, and every movement needs now and then to honor its own members and its contributions to the ongoing, continually unfolding story of rebellion, resistance, and revolution.

Jonah Raskin is the author of Revolution for the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman, and American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the Making of the Beat Generation.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments