Is the media to blame for Latinos’ absence in the debate about police-community relations? Recent waves of protests over police killings of African American men have led several journalists to speculate why Latinos haven’t received equal attention.

The explanations vary, but most center on the black-white binary and the media. Voto Latino’s Maria Teresa Kumar argued that “I think the media does a great job of wanting to silo who we are as Americans…They’re like, ‘Oh, that’s the immigrant issue, that’s the African-American issue, that’s the Asian issue.’ No, it’s us.” Telesur English joined the conversation when it published an article with the headline “5 Latinos Killed by U.S. Cops This Week—and Media Ignored It.” Actress Rosario Dawson commented on the black-white binary, stating, “We don’t hear about the many Latinos killed by police because, as a country, we’re used to binary [black-and-white] story lines.” Actor John Leguizamo talked about the need for Black and Brown unity. Others even have cited statistical limitations.

All these claims have validity, but they exonerate the complicity within the Latino community that has also led to this neglect. There are three other factors at play.

First, some major Latino media and political organizations have an abysmal record of covering victims of police brutality and subsequent protests. Second, Latino political advocates’ efforts to portray all Latinos as upward-mobile newcomers undermines problems affecting the large proportion of people who live in poverty. Finally, the newcomer perception, largely enforced by American political culture, erases the history of anti-police brutality activism and urban riots sparked by violent police confrontations in the community.

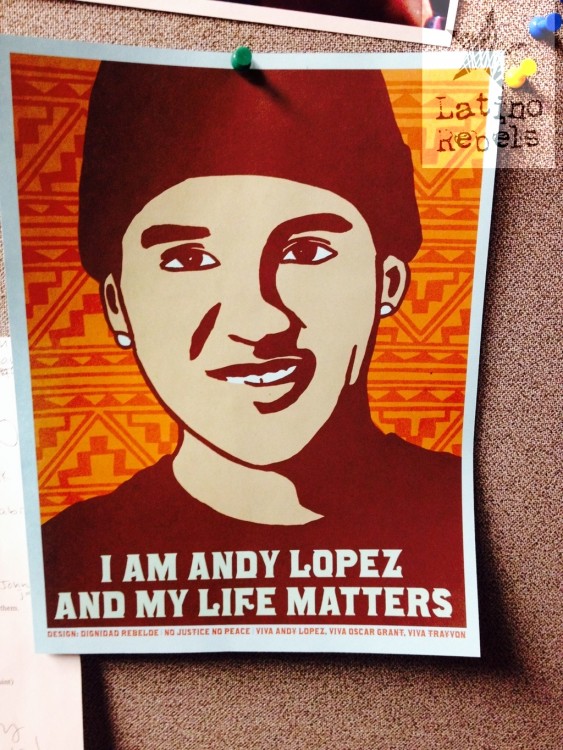

It is important to note that various writers have attempted to highlight this issue for years. After the 2013 police killing of 13-year-old Andy Lopez, a teenager shot by police in Santa Rosa, California, after an officer mistook a toy gun for an assault rifle, Latino Rebels founder Julio Ricardo Varela wrote an op-ed on NBC Latino and asked, “How many national Latino organizations shouted in front of TV cameras that justice be served?” Latino Rebels also spent a considerable amount of space covering the 2013 death of David Sal Silva. Writer Sabrina Vourvoulias [penned a piece](http://aldianews.com/articles/politics/security/why-do-i-cast-no-shadow/...( about police brutality and noted the political divisions within the Latino community. “Latino activism remains resolutely divided by region, national origin and documentation status,” she said. Many have raised unique perspectives, but these voices often go unheard in the mainstream.

Latino Media and Political Organizations

Until late last year, most major Latino media and political organizations barely reported on police brutality against Latinos. It was only in October 2015 that the National Council of La Raza announced that it would study police-community relations. Recently, several major Latino media outlets have noted the deaths of Anthony Nuñez and Pedro Villanueva, two teens killed by police in California. However, this level of coverage didn’t happen with other unarmed Latino teens like Hector Morejón of Long Beach, California in April 2015. Morejón died when an officer spotted him in a vacant building and shot him after believing Morejon pointed a gun. Police never recovered any weapon from the scene. Protests were local. Morejón’s name has largely been forgotten.

This has changed recently. In March, Univision anchor Jorge Ramos did a segment on Texas teen Jose Cruz. Cruz and his friend, Edgar Rodriguez, were breaking into an SUV attempting to steal car seats.

Off-duty Farmers Branch Officer Ken Johnson spotted the two boys and chased after them. Johnson crashed into the back of the boy’s vehicle, exited his car and fired upon them, killing Cruz and injuring Rodríguez. Even though the two boys were unarmed, Johnson claimedthat he feared for his life. The protest over Cruz’s death in May remained a local news story. What’s even more starling is that while NBC had originally reported on the story, NBC Latino, which shares all Latino-related news published by NBC, never shared the story with their followers on social media.

Even when national media outlets cover Latinos who were victims of police brutality, major Latino media outlets appear oblivious to the stories. In February 2015, ABC’s Good Morning America and several major outlets such as CNN and the Los Angeles Times reported on the beating of Najee Rivera. In May 2013, surveillance video captured Philadelphia police officers Kevin Robinson and Sean McKnight viciously beating Rivera after a car chase. The officers clipped Rivera’s motor scooter during a chase that began after he ran through a stop sign They charged him for aggravated assault. Rivera’s girlfriend tracked down the surveillance tape and used it as evidence in a grand jury investigation Robinson and McKnight were suspended and later dismissed from the force. However, in April 2016, a jury acquitted both officers of all charges.

The beating of Najee Rivera is an egregious example of the failure of police accountability, but why did so few Latino media outlets report on it when it was a national story? Rivera admitted to running away from the police because “I was afraid… I saw them get out of their car with nightsticks. I heard one of them call me a spic. I hadn’t done anything wrong, so I took off. I shouldn’t have, but I was scared of them.” It’s not as if other Latinos in impoverished urban communities don’t share this fear. Many can probably relate. It is possible that since the media has labeled police brutality as an “African American issue,” there is fear of racialization among some people within the Latino community. Classifying police brutality as a “Latino issue,” for some, means aligning themselves with African Americans, thus “assimilating” as a racialized group.

The Upward-Mobile Newcomer Narrative

To counter anti-immigration sentiment and other stereotypes, some Latino political advocates have sought to reconstruct how society views Latinos. In March, CBS anchor Charlie Rose held a discussion with Sol Trujillo, Aida Alvarez, and Henry Cisneros, who are board members of the Latino Donor Collaborative, a non-profit organization aimed to “reframe and advance an accurate perception, portrayal and understanding of the important contributions Latinos make to American society.” Throughout the interview the three guests, who all have backgrounds in business or politics, focused only on “positive” facts about Latinos. When Rose asked them what Americans should think about when they talk about Latinos, Trujillo responded by stating that they are people “who are here who are aspiring to be Americans.” This response is indicative of the Latino elite’s effort to portray all Latinos as a newly arrived group that is still in the assimilation process, even though assimilation doesn’t mean upward mobility.

Although upward mobility has risen within the Latino community, this narrative omits an important factor. In a recent op-ed in UC Berkeley’s The Daily Californian, staff writer David Gayton said, “The rise in upward mobility noted within these surveys correlates with the rise in the overall Hispanic population.” He also warned of negative consequences by only focusing on the growing middle-class:

This desire to present Hispanics as traditional, hard working middle-class Americans [sic] is problematic. This approach perpetuates the hierarchies of power that place white conservative values at the apex of what it means to be successful. Also, by focusing on the positive image of Hispanics as a marketable and expanding middle class, the needs of the large number of Hispanics who still live under the poverty line are left unaddressed…To say that the dream of upward mobility based on meritocracy is open to everyone is therefore a pernicious simplicity that disregards all the socioeconomic factors that make that social ascendance possible.

While creating this image of Latinos as upward mobile is understandable, this class-based initiative creates a sanitized image of Latinos and renders the issue of police brutality invisible, since it largely affects the poor and working class. It also labels high poverty rates among certain subgroups as the result of their recent arrival rather than structural changes in the economy as well as a history of discrimination that prohibited social mobility for groups such as Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans.

Some have challenged this public narrative by arguing that mass incarceration and police brutality are Latino issues. A recent op-ed in the Huffington Post that called for Latinos to support sentencing reform said “Make no mistake: criminal justice reform is a Latinx issue.” NPR’s Latino USA republished an op-ed where writer Máximo Anguiano argued that “The history, fate, and experience of Latinos and Blacks in this country will forever be intertwined.”

There appears to be a growing divide within the Latino community between people who have accepted the fact that the group has and continue to share many concerns with African Americans and those who wish to portray the group as the next “model minority” by casting them as holding conservative values and being “more American than Americans.” The latter effort largely benefits the middle- and upper-middle class at the expense of the poor and working class. It’s easier to discuss Latino-owned businesses in Detroit than the youth homicide rate in Salinas, California. It’s more comforting to focus on increasing Latino homeownership rates than on the low high school graduation rates of Latino males in Pennsylvania. This conversation, however, should note that while Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans have shared and overlapping histories with African Americans, this is not as true with groups such as Colombians and Argentineans, who since the 1980s have arrived to the United States with an educational attainment higher than the national average.

Historical Context is Missing

In almost every piece written about Latinos and police brutality, writers have rarely mentioned the long history of Latinos fighting against police abuse or the numerous urban rebellions sparked by violent police encounters. There is a long history of tension between Latinos and police departments primarily because police have viewed some groups like Mexicans as inherently criminal. One Chicago police sergeant in the 1930s stressed this by claiming, “Indian blood and Negro blood does not mix very well. That is the trouble with the Mexican; he has too much Negro blood.” This kind of attitude, and the perception of economic competition between Mexicans and Whites, led the police to use discriminatory and violent tactics against Mexicans in Chicago.

Politicized by the civil rights and Black Power movements, Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans created political organizations to fight against police brutality and other issues in the 1960s. While there are well-known organizations such as the Young Lords Party and the Brown Berets, largely because they had multiple chapters in different states, organizations that never expanded beyond their local communities such as Oakland’s Chicano Revolutionary Party, San Jose’s Community Alert Patrol, and Denver’s Crusaders for Justice are not well-known.

In response to recent police killings of African Americans and Mexican Americans, Chicano activists in the east side of San Jose, California formed the Community Alert Patrol (CAP) in 1968 to challenge the nearly all-white San Jose Police Department. The groups originally went by the name “United People Arriba,” which was a multi-issue, multi-ethnic organization to meet the diverse concerns of residents on the east side. Adopting a similar method to the Black Panther Party, CAP followed police vehicles with tape recorders and video cameras to record police abuse. Former CAP member Doreen Garcia Nevel recalled, “The police hated us with a passion because we would show up with our cameras, tape recorders to capture them doing their dirty deeds.” Decades before cell phone cameras captured police brutality, Chicano activists in San Jose understood the significance of capturing it on film.

Even monumental events in Latino history go unacknowledged. For example, June 12 marked the 50th anniversary of Chicago’s Division Street riots, which were the first major Puerto Rican riots in the United States. Despite this milestone, commemorations occurred only in Chicago. Acknowledgements didn’t appear in any major news publications. This lack of awareness reveals how poorly Latino history exist in public life. Although some might wonder why anyone would want to acknowledge riots, refusing to learn from this risk the possibility of another incident happening again.

Critics of America’s racial discourse cannot solely blamed the black-white binary, statistical limitations, and the media for the absence of Latinos in the police brutality debate. Indeed, there have been major protests over police killings in Latino communities that received little attention, but how can these incidents reach a national audience if major Latino media outlets and political organizations are barely covering them? Former president of Los Amigos of Orange County Amin David’s comment that “Immigration occupies a big part of our table… It squeezes out the police component,” doesn’t help. Nor do many comments I’ve seen on social media that claimed Latinos “aren’t likely to support criminals,” “don’t play victim,” or “don’t have to protest because they know that pendejo deserved it.” Anger over the lack of coverage shouldn’t emerged only when the issue is in the news regarding African Americans. This pattern of selective outrage neglects the grievances of families who lost loves ones when the issue wasn’t dominating headlines.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments