This was Day 11 of the life Keith Griffin never imagined. He’d viewed himself, before the flashpoint in Ferguson, foremost as a father, a magazine publisher, a gym fanatic, an early sleeper. Now he barely got to see his kids. He hadn’t been to the office since who-knows-when. He sometimes stayed on the streets past 1 a.m., catching traces of tear gas in the strip mall neighborhood he once considered ordinary.

Griffin’s life, like so many of those connected to Ferguson, has now become a nightly roulette game, his evening hours spent in the volatile quarter-mile where police square off with protesters.

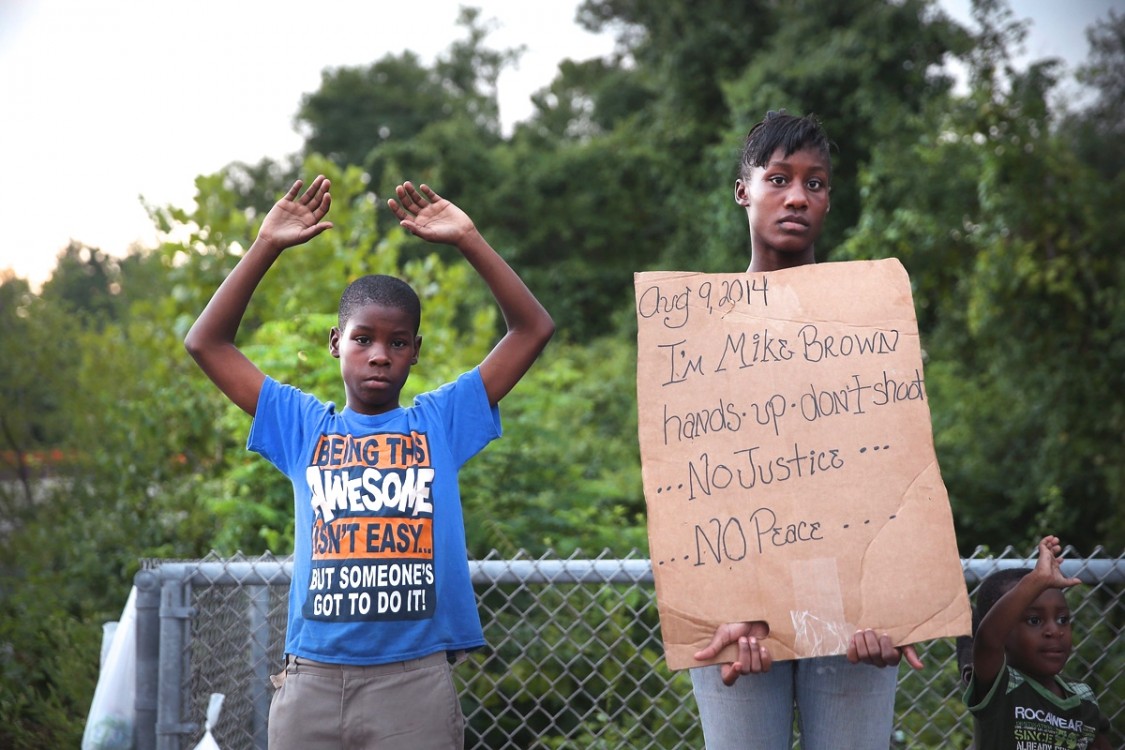

Griffin is there, he says, because he wants police accountability for the killing 11 days ago of unarmed teen Michael Brown. But Griffin is also there because the shooting unearthed in him powerful and once-latent feelings — about race, about community, about his responsibility in times of crisis.

What’s going on in Ferguson is too complex to explain from just one man’s perspective. But Griffin’s experience in the last week-and-a-half helps illustrate why so many have been interrupting their lives to take to the streets, pausing jobs and studying and parenting for something they consider more important.

“I don’t want this to be ‘hoo-rah hoo-rah’ and then it all goes away,” Griffin said.

Griffin has become something of a leader on the streets almost by accident. On Day One, hours after the shooting, Griffin, 37, headed to Ferguson by himself on a fact-finding mission. Nothing official had been said about the circumstances of the shooting. He was curious.

By nightfall he was convinced there had been some kind of injustice. And he soon posted on Facebook a message listing other black men who’d been killed — Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, Jordan Davis.

“Ain’t much changed,” Griffin wrote. “We need a leader to rise up and organize our anger, fears, and oppression.”

“Well said,” one friend told him.

“Gotta break the cycle,” said another.

“It’s time,” another said, and by Day Two Griffin had organized a “team” — his wife and a few friends — who were buying food for protesters and urging them to stay peaceful.

Griffin’s mission grew. He started buying chicken wings, pizzas, spending $150 per night. He’d roll up to West Florissant Avenue, ground zero for the protests, with 30 pizza boxes stacked in the back seat of his Audi. He’d distribute them at a folding table, and folks would come by before nightfall. Women with children in strollers. Shirtless teens with cargo shorts. Elders in monochrome suits. All races.

“My thing, it’s not about black and white,” Griffin said. “I’m out here because we need answers.”

But that’s just one part of Griffin’s thinking. It is about race, he says. He’s thought a lot about race in the last few days, and some of his white friends perceive events in Ferguson in ways that make him bristle. And they probably don’t understand the little things that define his day-to-day life. The hurdles he faces renting a downtown business property, something he attributes to race. The way he was pulled over last week in another part of town, questioned about whether his car belonged to him. The way he’s had to talk with his 8-year-old son about how to deal with cops. (“Yes sir, no sir.”)

“There’s a difference in psyche between black and white culture,” he said. “I guess there has always been a divide. But there’s never been a good platform where you could say it.”

Blacks, he says, are too often considered to be at fault.

Like those protesters in Ukraine, in Egypt. “They’re perceived as freedom fighters,” Griffin said. “But here, we’re out on the streets doing the same thing and we’re animals.”

Griffin grew up in Ferguson. He rode his bike through the main streets and played basketball at McCluer High School. Griffin now lives 15 miles away and publishes a glossy magazine, Delux, that caters to young and fashionable African Americans. He admits, with some prodding, that he’s one of the wealthier people involved in the Ferguson protests.

“I’m just trying to make this thing easy on everybody,” he said as he started Day 11 with a stop at Little Caesars, 30 more pizzas stuffed into his car.

Griffin arrived at the protest site just after 6 p.m., and he wasn’t sure how it would go. Some days devolve. At least one has stayed calm all through the night. But he tried to make sure everybody had at least some degree of comfort. He sent a friend to buy ice for a water cooler. He shook hands with people he knew only by face. He waited for the sun to set.

By 9 p.m., there were several hundred protesters moving up and down the street. And an area so ordinary by daylight — nail salons, check cashing stores, a McDonald’s — had turned once again into an ominous arena, police waiting off to the sides. In earlier nights, Griffin felt the police were premature to cordon or intimidate protesters. If people on the street were acting out, it was in part a response to police action, he said.

“Almost like a tiger,” Griffin said. “Put it in a cage, and if you keep poking at it and prodding, eventually he’s gonna growl.”

“But I don’t want to have any more clashes, man,” Griffin’s friend, Al Cole Jr., said. “I just want a peaceful night.”

“Tell me about it, man,” Griffin said.

For a while, Griffin watched the protesters from the sidewalk. Then, pizza gone, garbage packed up, he decided to join in. He started muttering the words but then was screaming them. “We young, we strong, we marching all night long,” they said.

They were told by the cops to keep moving, and so they did — up the street and back down. The group walked several miles total.

Then Griffin bowed out. It was 11 p.m. and he was tired and he sensed that this night, relative to others, might not get violent, as police for the moment were keeping their distance.

“It’s not as tense as I thought it might be,” he said.

So he headed back to his car, told his wife he was coming home, and texted a few friends that he was safe.

It was time to rest up for Day 12.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments