This is Part 25 in a series about Radical Municipalism looking at ways people worldwide are organizing in their cities to build power from the bottom up. Read Part 1 (Brazil), Part 2 (Rojava), Part 3 (Chiapas), Part 4 (Warsaw), Part 5 (Bologna), Part 6 (Jackson, Miss.), Part 7(Athens), Part 8 (Warsaw & New York), Part 9 (Reykjavík), Part 10 (Rosario, Argentina), Part 11 (Newham, UK), Part 12 (Valparaiso, Chile), Part 13 (Porto Alegre, Brazil), Part 14 (Montevideo, Uruguay), Part 15 (Venezuela), Part 16 (Cape Town), and Part 17 (Congo), Part 18 (Jemna, Tunisia), Part 19 (Gdansk, Poland), and Part 20 (Senegal), Part 21 (Mumbai, India), Part 22 (Vietnam), Part 23 (Japan), and Part 24 (Catalonia).

“Tourism is making Barcelona’s housing too expensive for locals. Loud parties, people defecating in the streets and disturbances are minor problems, compared to rising rents," said David Castro, an activist with Barcelona En Comú (Barcelona In Common), speaking in 2017. "Tourism eats cities, like in London or San Francisco.”

That year, En Comú, the political party that governs Spain's second largest city, introduced a plan – abbreviated as PEUAT – to tackle tourism. The party, which was formed by activists and residents to upend traditional local elections, has run the city since 2015.

“This is novel, a direct action to seriously reduce tourism,” Castro explained.

Globally, tourism often goes unquestioned. Business as usual means property generates profit. But, “PEUAT is a zoning plan, creating different rules for opening hotels and tourist apartments,” Kate Shea-Baird, from En Comú’s governing executive, told me in an interview here last year.

Today, Barcelona promotes de-growth in the city center while encouraging limited tourist growth in the city's periphery. En Comú expected resistance to its plan, especially from opposition parties.

Instead, neighbourhood housing movements pushed the council to expand the de-growth zone. The result: “PEUAT became even more ambitious than we hoped,“ said Shea-Baird.

Reclaiming the city, barrio by barrio

En Comú's new politics emphasizes words like “neighbours”. I asked En Comú participant Federico Gatti why "neighbors" often replaces “citizens” – or more neoliberal words like “consumers” and “taxpayers.”

“You can be a neighbour without citizenship, as I was,” said Gatti, a native-born Argentinian. “The way we relate breaks the anti-political narrative of neoliberalism. Politics is beautiful: You do it whether you like it or not. When a baby cries its makes a demand. That’s politics. We must recover politics for people."

Some of Barcelona's most radical innovations have recovered homes for neighbours and neighbourhoods. The council has increasingly fined property speculators – most recently vulture funds – for keeping properties empty.

Today, social housing is being built, including in the former prison Modelo, in places once destined for luxury flats. With an expanded housing budget, the council is able to intervene to reduce evictions and support victims of gentrification.

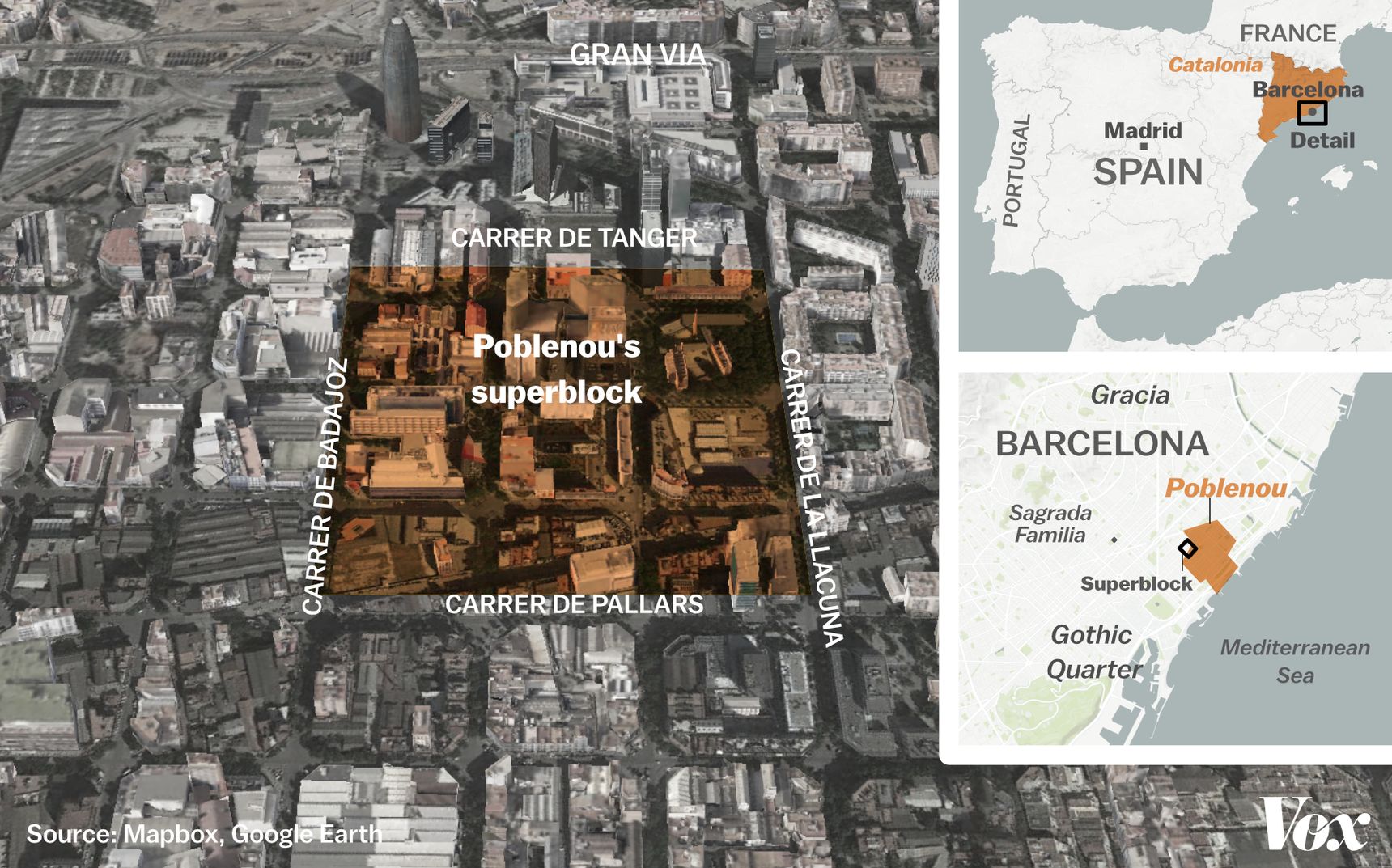

But regenerating neighbourhoods goes beyond retaining neighbours. “Superblocks” are being rolled out – zones where people and bikes roam freely and cars are discouraged, promoting a more environmental and people-friendly city.

More broadly, neighbourhoods in Barcelona are becoming a key building block for participatory democracy. Neighbours regularly meet in public assemblies. En Comú crowd-sources proposals through an online digital platform and assemblies where popular ideas are pushed on city hall.

I attended an assembly last year in Poble Nou, where Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau visited to hear concerns, particularly ones focused on tourism and housing.

Neighbour input is changing things at the micro-level – like making the square in which I interviewed Castro more resident-friendly – and promoting city-wide projects co-formulated with the population through online mechanisms.

For instance, the public vocally backed Barcelona’s plans to municipalize its water services and create a municipal energy company. Broad participation has been at the core of En Comú since it formed through a convergence of activist groups.

"La nueva política"

Other cities have formed similar political confluences that took over city halls across Spain in 2015. And this coming Sunday’s election, on May 26, will test the "new politics" of the region. Working as a decentralized network, Barcelona and Madrid are leading a charge against the Spanish and European anti-migrant policies that have caused thousands to drown in the Mediterranean, with many more detained without trial.

The new politics also includes cities limiting the salaries and perks for politicians and civil servants. In Madrid, the "sustainability of life" has become one of the council’s core values through its "Ciudad de los Cuidados" (City of the Citizens) initiative.

The Spanish capital has also re-municipalized funeral services and increased public spending while lowering debt. The Andalucian city of Cadiz has meanwhile made its own leaps into green municipalism, and many councils, like Zaragoza's, have introduced participatory budgeting.

But the new politics also faces resistance from the Spanish state. This has been especially clear in Madrid, where Mayor Manuela Carmena has lacked the courage to defy austerity imposed from a strong conservative opposition and central government. Instead, in 2017, she sacked her finance minister, Carlos Sánchez Mato, who wanted to go further with progressive reforms. Challenging state power – and receiving pushback against their efforts – is unavoidable for radical municipalists.

One answer to the state response has been to rupture the status quo, as in the case of the radical independence municipalists of Catalonia – profiled here last week – who will also be vying for power in elections this Sunday.

Barcelona En Comú’s approach to state power has three aspects. One, it defies the government, for instance by challenging immigration policies. Second, it allies with the Spanish center-left Podemos party, which seeks to strengthen its national power (though Podemos has failed to live up to its democratic origins and holds an uncomfortable middle ground on the issue of Catalan independence.) En Comú's third stand – and arguably its most ambitious – is to reclaim the world, city by city.

Fearless Cities

“To win Barcelona for the common good, we need other people around the world to act in the same way: to come together with their neighbours, to imagine alternatives for their town or city, and to start to build them from the bottom up. This is just the beginning," writesGerardo Pisarello in his introduction to "Fearless Cities," a new book about the growing global municipalist movement.

Published earlier this year, the work is an essential handbook for taking back cities. It features themes from fighting fascism to promoting public transport, from protecting public space and other urban commons to creating radical democracy.

The chapters often provide a mini-manifesto. On enabling radical democracy, one message is that any single democratic tool might exclude some people, so it therefore aims to create a "participatory ecosystem". The book stresses that these are ideas to adapt – they are not a uniform blueprint – as municipalism isn't a one size-fits-all model.

En Comú started Fearless Cities with a convergence in 2017 that has since spread across continents. Now, Fearless Cities, as both book and network, shares tactics for people everywhere who seek to win back their city – from building a political confluence and crowd-funding to creating a code of ethics and employing a "technopolitics" to communicate seamlessly on-and-offline.

Fearless Cities stresses taking action: seizing the low hanging fruit as you harvest higher. One central theme is feminizing politics. Each chapter gives activists practical tips on how to dismantle patriarchy, including an excellent guide – by Marea Feminista of A Coruña – on ways to stop male voices from drowning out everyone else.

In the Spanish context, feminizing politics has shown itself particularly strong, featuring huge women's marches and strikes. The movement is trying to break the post-Franco legacy, which entails a struggle to overcome gendered violence and sexism that is more entrenched than in most countries of the global north.

This book – like this series, on Rebel Cities – shows a radical municipalist world in the making, and explains how it is being created today. Concluding the book, Ada Colau, Barcelona's progressive mayor, reflects on the first Fearless Cities convergence from two years ago.

“It was a public proclamation, a cry to the heavens that we wanted, together, to move towards a better future," she writes.

"In a brave, united voice, we said loud and clear that we wanted to change the world, working at the local level through concrete actions and policies that not only improve people’s lives, but also show that there is an alternative, and that politics should work for the many and put people at the center.”