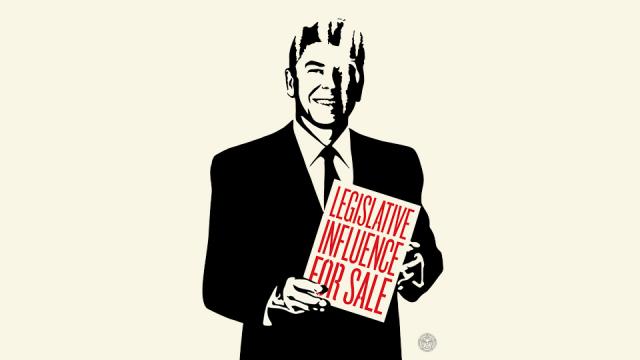

Money is said to be the mother’s milk of politics, a phrase supposedly coined by Big Daddy Jesse Unruh, a feisty Democratic politician from California. If so, we have an awful lot of it pouring into our elections — and we may be about to open another floodgate.

More than $6 billion was spent in the 2012 election cycle — a record amount. That mark was set in part because of the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision that reversed decades of legal precedent and allowed corporations, unions and individuals to spend unlimited amounts on elections in the name of free speech. But the decision did not affect limits on contributions to candidates.

The Center for Public Integrity has described in detail what Citizens United meant in the world of money and politics. We also profiled thetop 25 “super donors” and others who took advantage of the decision to pump nearly $1 billion dollars into super PACs last year. For example, the No. 1 super donor was casino magnate Sheldon Adelson, a Republican who spent about $100 million, including some $40 million in the final weeks of the campaign.

Now the Supreme Court is weighing another decision — whether to eliminate the so-called “aggregate” limit on an individual’s contributions to candidates, parties and political action committees. Total contributions to multiple candidates are capped at $48,600 for the 2013-2014 election cycle.

There is also a combined limit for giving to parties and PACs, currently set at $74,600, making the combined overall limit for the current election cycle $123,200. The $2,600 limit per candidate is not thought to be in play, though Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., would do away with that as well.

The aggregate contribution limits are being challenged in McCutcheon v. FEC, named for its lead plaintiff Shaun McCutcheon. McCutcheon is an Alabama general contractor by trade and a Republican activist, who incidentally exceeded one of the limits himself last year by $1,000.

His lawyer said this amount would either be refunded or re-gifted after the Center for Public Integrity pointed out the violation. In court, his lawyers have argued that the aggregate limits, which are indexed to inflation and periodically raised, restrict his First Amendment rights

As the Center also reported this week, U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli Jr. vigorously defended the aggregate limits during the McCutcheon case’s oral arguments on Tuesday.

"Aggregate limits combat corruption," Verrilli told the nine Supreme Court justices, arguing that should party leaders such as the speaker of the House or Senate majority leader solicit seven-figure checks, there is an "inherent risk of corruption" and a "risk of indebtedness" to wealthy donors.

If the court were to axe the current overall contribution limits, Verrilli predicted that "less than 500 people" could "fund the whole shooting match," and then the government would be "run of, by and for those 500 people."

In fact, about 600 individuals hit the then-$46,200 ceiling for campaign donations to federal candidates during the 2012 election cycle, according to an analysis by the Center for Responsive Politics at the request of the Center for Public Integrity.

About 45 percent gave overwhelmingly to Republican politicians, while about 37 percent gave with the same fervor to Democrats. The rest gave to a mix of candidates in both parties. And about 1,700 donors maxed out on their donations to national party committees, hitting the then-limit of $70,800 during the 2012 election. Again, the GOP made out better than Democrats, collecting about 61 percent of those donations.

If the court lifts the aggregate limits, a major contributor such as Adelson, for example, could then give more than $3 million directly to candidates and parties. In the last election, Adelson gave a combined $44,500 — just shy of the then-$46,200 aggregate limit — to 16 Republican candidates including McConnell, Republican Speaker of the House John Boehner and Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney.

An aggregate limit on political contributions was enshrined into law by Congress in the wake of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s. The government has been consistent, though not always effective, in attempting to insulate elections from the corrupting influence of corporations and labor unions.

Congress first banned corporations from funding federal campaigns in 1907 with the Tillman Act. President Theodore Roosevelt, the great reformer of the Gilded Age, said at the time that such a prohibition would be “an effective method of stopping the evils aimed at in corrupt practices acts.”

In the 1976 Supreme Court case known as Buckley v. Valeo, the court upheld limits on contributions to candidates, saying they were “primary weapons against the reality or appearance of improper influence stemming from the dependence of candidates on large campaign contributions.”

But the court rejected limits on expenditures, arguing that such restrictions “limit political expression at the core of our electoral process and of First Amendment freedoms.”

And that balancing act — protecting free speech versus keeping government free from corruption — remains at the center of the debate over campaign finance reform. Whatever the current Supreme Court decides, massive amounts of money by any definition will still find a way to aid candidates and parties, via traditional political groups and new super-sized players. And the legalized version of political corruption we have permitted in our electoral system will no doubt continue — perhaps until some other Watergate-like tipping point convinces the public and future courts that elections need to be about more than unlimited amounts of money.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments